Quite a bit has been written lately (mainly in the liner notes of albums featuring jazz guitarists) about the “liberation of the jazz guitar”. The chief liberator was of course electric amplification, which came along towards the close of the ’Thirties and completely altered the role of the guitar in jazz, taking it from the anonymity of the rhythm section and giving it a strong voice of its own, one on equal footing with the horns. As a result, the guitar quite naturally adopted a single-line, many-noted, horn-like approach, an approach which finds its fullest expression in the work of Charlie Christian and, more recently, Barney Kessel, Tal Farlow, Jim Hall, Chuck Wayne, Jimmy Raney, Kenny Burrell, Mundell Lowe and Herb Ellis, among others.

The continued usage of this horn-like approach has inevitably resulted in a corresponding de-emphasis of those characteristic instrumental techniques which are peculiar to the guitar, techniques best exemplified in classical and Flamenco guitar music. These two approaches rely for their effectiveness on a complete exploitation of the instrument’s potential, mixing melodic, contrapuntal and harmonic elements in an astonishing complexity, and utilizing to a greater degree the elements of dynamics, shading and tonal contrasts.

A few attempts have been made to fuse the classical and jazz approaches, but generally these experiments have been as unsuccessful as they have been provocative. Brazilian guitarist Laurindo Almeida’s work with jazzman Bud Shank was a positive step, but left much to be desired in the matter of jazz feeling. The most completely satisfying results so far have been provided by Washington’s Bill Harris (no relation to the ex-Hermanite trombonist of the same name), whose striking work in two Emarcy albums has wedded both approaches neatly.

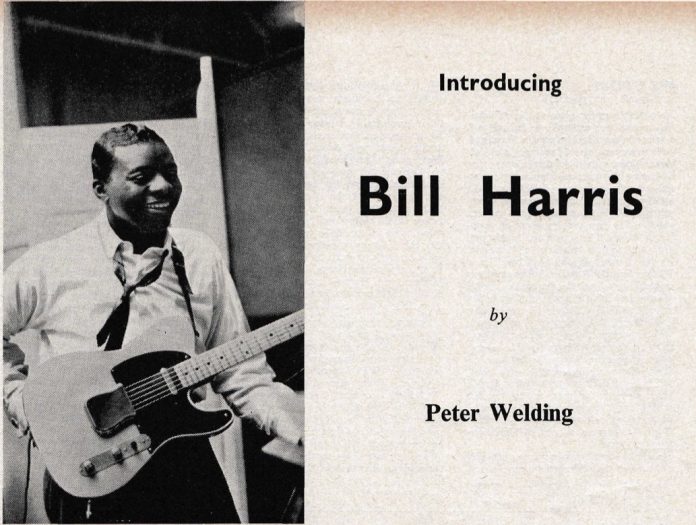

Bill’s working background is surprisingly akin to that of many young jazzmen on the present day scene in that he served a long apprenticeship in the Rock ‘n Roll field – he was the featured accompanist of the celebrated R&R group, The Clovers, for over five years. Prior to joining The Clovers Bill had studied classical guitar with the famed Washington, D.C. guitarist and teacher Sophocles Papas (a former pupil and close friend of Andres Segovia) and it was on the long gruelling road tours with the R&R group that Bill brought to a fine polish the fusion of jazz and legitimate guitar techniques. New York guitarist Mickey Baker heard Bill practising one day and was so impressed that he recommended him to Bob Shad, then director of Emarcy Records, the jazz subsidiary of the Mercury Recording Corporation. Bill recorded one album for Emarcy, Introducing Bill Harris, which was so successful that it was soon followed by a second, The Harris Touch. As of this writing a third album is in the can, to be released shortly.

When he isn’t teaching guitar, both classical and jazz, at his Washington studio, Bill is often on the road, appearing as a featured solo attraction. He prefers concert work to night club engagements for the simple reason that he finds the atmosphere more congenial and the audiences more attentive and appreciative. He makes frequent concert appearances at a number of colleges and universities on America’s Atlantic coast and often appears in recital before the highly demanding audiences of several of the classical guitar societies in the larger cities. It was at a concert he gave at the Philadelphia Classic Guitar Society that I first met Bill.

He is a tall, well-built, muscular man with a shy, ingratiating, almost hesitating manner about him. Hunched over his guitar, in the classic guitarist’s pose, one foot propped up on the small wooden block, all hesitation disappears as the guitar comes alive in his large hands. He follows much the same format in all his concert appearances; at the Philadelphia recital, for example, he led off with a trio of short Bach pieces, a Saraband, a Prelude and an Allemande, and followed these with a Scarlatti Sonata and a Chopin Prelude, all flawlessly executed – to the obvious delight of the audience, most of them guitarists themselves – before he embarked on a program of his own arrangements of popular standards. These included highly pulsant and lyrical versions of Stompin’ At the Savoy, Moonglow, Once In A While, Out Of Nowhere, Possessed (an original based on the harmonic line of These Foolish Things), I Can’t Get Started, All The Things You Are, Liza and Lover. He concluded the program with a medley of three traditional Negro spiritual themes (Down By The Riverside, Swing Low, Sweet Chariot and Nobody Knows The Trouble I’ve Seen) which he had brought together into a short suite to be used as the musical setting for the recitation of a number of texts from James Weldon Johnson’s God’s Trombones, a book of Negro sermons in verse.

Harris’s arrangements veer sharply away from the advanced harmonic writing of the modernists. Instead, he sticks within the traditional harmonic framework of swing music, an area in which he is comfortably at ease and in which he has accomplished some truly fine and sensitive jazz work. Actually, Bill has not been greatly impressed by the work of the modernists, one infers from his comments, though he immediately follows this up with the statement that he finds something good in any kind of music that’s played well and has something valid to say. Bill’s work has much the same beauty, lyricism, charm (and solid strength as well) as the playing of such stalwarts as Benny Carter, Johnny Hodges and Harry Carney. And his R&R backgrounds insure a solid and propulsive swing in all that he does.

Bill’s work has much the same beauty, lyricism, charm (and solid strength as well) as the playing of such stalwarts as Benny Carter, Johnny Hodges and Harry Carney. And his R&R backgrounds insure a solid and propulsive swing in all that he does

Anyone who has ever attempted to play classical guitar and is aware of the difficulty involved in merely executing a written score, can doubly appreciate the fact of Bill’s improvising within this discipline. I was pleased to hear at the Philadelphia concert that the numbers as Bill played them then differed markedly from the recorded versions of the same tunes – the difference being due to improvisation. Bill stated that he had begun extemporizing on the themes after discussing the matter with a close friend. Both concluded that only by experimenting, by continued spontaneous expression – in short, only through improvisation – could the approach he has pioneered remain fresh, alive and valid. Also, this was the only way it could advance.

Does Bill have any plans to form a group of his own? Yes, he says, he’d like to assemble a small group; the problem would be in finding the right instrumental combination. The other horn(s) should not intrude overly on the unamplified guitar sound. He has been impressed with the blending of flute and guitar. “One night we were playing an engagement at a Montreal hotel. This was when I was still with The Clovers. There was an Afro-Cuban band playing in another room and after the sets the flute player from the band and I started working out a few tunes. It sounded pretty good. Maybe something like that would work out. Or an alto, even.” In the meantime, Bill is completely happy working as a single. The excellent results he has achieved, both in person and on his recordings, would certainly justify his continuing in this direction if he so chooses. But it would be exciting to hear him in a really compatible small group setting. I’m looking forward to it. And Bill is, too.