It’s a 1980 recording done for the German radio station Norddeutscher Rundfunk, so the audio quality is exemplary – not something that can be said for all the previously unreleased material coming out now. Why it’s taken 40 years to appear isn’t apparent. It’s hard to imagine it was lost. Perhaps the delay was to do with contractual business.

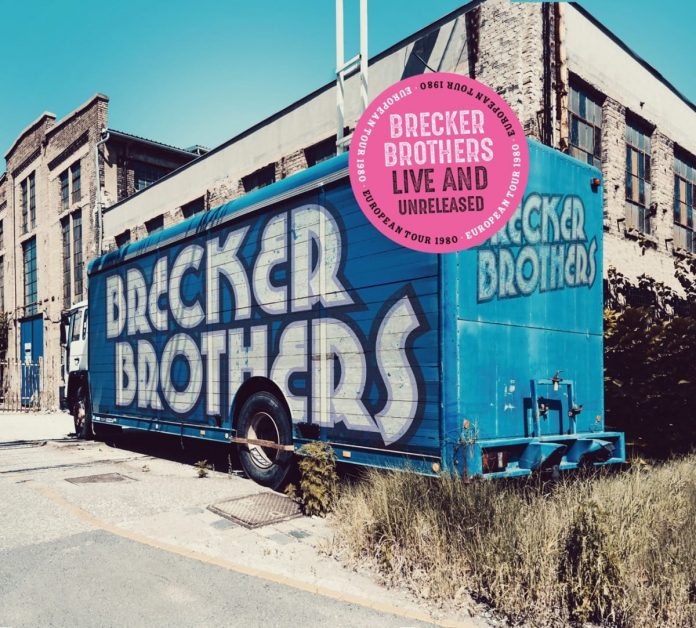

Jazzline havent skimped on the packaging, giving the music the presentation it merits. It comes in a well illustrated trifold digipack with an annotatory booklet containing background and analysis by the reliable fusion scholar Bill Milkowski, commentary from Randy Brecker and a wealth of period photos.

The musical vocabulary has obviously been known a long time, and although it’s dated in some respects, a good 75% of it hasn’t been surpassed; it’s as if this highly progressive period in American musical history was discredited and largely frozen out after the advent of Wynton and the revivalists in the early 80s. Many sustained and developed the fusion style, of course, but the mainstream of jazz took a different, far less ambitious path in the decades that followed this concert.

Except for Richie Morales the lineup is the one that recorded the mind-blowing Heavy Metal Bebop in 1978, and the mood is pretty much the one found on that album. The clue’s in that perfectly judged title, although “funk” is probably missing. It’s mostly loud, hence “metal”, but it’s almost always funkier than that term implies. The bebop bit is, of course, the athletic, comprehensive enumeration of harmonic possibilities evident in the composition and improvisation.

Strap Hangin’ is a masterpiece of chromatic, polytonal composition from Michael Brecker over a deep funk groove, the modernism standing out especially after that sly baroque intro. There’s a beautifully sculpted bebop solo from Randy, and Mike does his signature insinuating slow entry before waxing lyrical and then working up a storm. Tracks like this suggest the Breckers developed 95% of the new potential of the 70s in throwing together jazz and its kin with new technology. There wasn’t much else for jazz to add after this.

Tee’d Off is a smoothish jazz-funk tribute to keyboard man Richard Tee. It’s perhaps a little overwrought for the relatively slender material. Finnerty has his first solo and demonstrates well the transitional nature of most jazz-rock guitarists of the time in adding then hip-to-jazz rock tonality to the mix but lacking the bebop grounding of jazz-rock’s horn players and keyboard players, who generally came from jazz. One exception that comes to mind is George Benson going chromatic on Paraphernalia on Miles Davis’s 1968 Miles In The Sky. But then, yes, George came from bebop and that tune was only incipiently jazz-rock, Williams maintaining a triplety ride cymbal most of the time. George didn’t, however have a fuzz pedal. Bebop plus fuzz had to wait until guitarists initially out of rock such as Scofield and Stern studied bebop – at least in the USA. In London Allan Holdsworth was already on to chromatic soloing with distortion in the mid-70s, though not via bebop.

Sponge is Randy’s dark, fourthy funk opus, in which new tech is flaunted by putting trumpet and tenor through wah-wah on the trading section. A word is due for Neil Jason, who doesn’t get a solo spot for his sterling bass playing. Virtuoso electric bass playing was in its infancy at that time, really only marked by Jaco Pastorius, Stanley Clarke and Jeff Berlin, but Neil Jason is very fluent.

Funky Sea, Funky Dew offers slow funk with tasty harmony. Finnerty takes his time in a long solo to insert a sizeable passage using false harmonics, much to the delight of the audience. The piece ends with Michael doing a long, unaccompanied coda as might Sonny Rollins. The track is 18.41 minutes, of which 9.11 is his well-developed, crowd-pleasing monologue.

I Don’t Know Either is a funky vehicle for more juicy modal solos, with Michael on fire, before we get another Randy classic, Inside Out. It’s essentially a 12-bar shuffle blues, souped up from bar five with spicy alternative changes. I’m not sure Mark Gray hits them all. It’s good to see Finnerty observing the altered changes, even if he’s not an “outsider” on static modal backdrops.

Baffled offers nicely souped-up changes over a funky disco beat. There’s a lengthy drum solo and it becomes evident in Randy’s straight-toned bebop solo that this is at core a fast samba.

The classics keep coming. Some Skunk Funk is Randy’s fiendishly convoluted theme that, as he tells Milkowski, has “become a rite of passage for young musicians”. Live recordings leave in the errors, such as Barry Finnerty’s stray note after the first theme statement and what seems to Michael’s choice of wrong key in the theme passage at 1.01. But it’s a murderously demanding piece.

East River is an anthemic rock riff, the easy bits of which Bruce Springsteen might have adopted, and was apparently required on Heavy Metal Bebop by Arista president Clive Davis to provide a single. The closer Don’t Get Funny With My Money has Randy’s self-consciously hammy vocals over an enhanced funk groove.

Nothing new then, of course, but a very well-produced document of the band at work live and consequently playing longer and closer to the edge. It’s also further evidence that jazz hasn’t moved on a lot since. Brecker and fusion fans should be delighted to have it.

Discography

CD1: Strap Hangin’; Tee’d Off; Keine Titelinformation; Sponge; Funky Sea, Funky Dew (57.51)

CD2: I Don’t Know Either; Inside Out; Baffled; Some Skunk Funk; East River; Don’t Get Funny With My Money (47.37)

Randy Brecker (t, v); Michael Brecker (ts); Mark Gray (kyb); Barry Finnerty (elg); Neil Jason (elb); Richie Morales (d). Onkel Pö’s Carnegie Hall, Hamburg, Germany, 2 July 1980.

Leopard/Jazzline D 77072