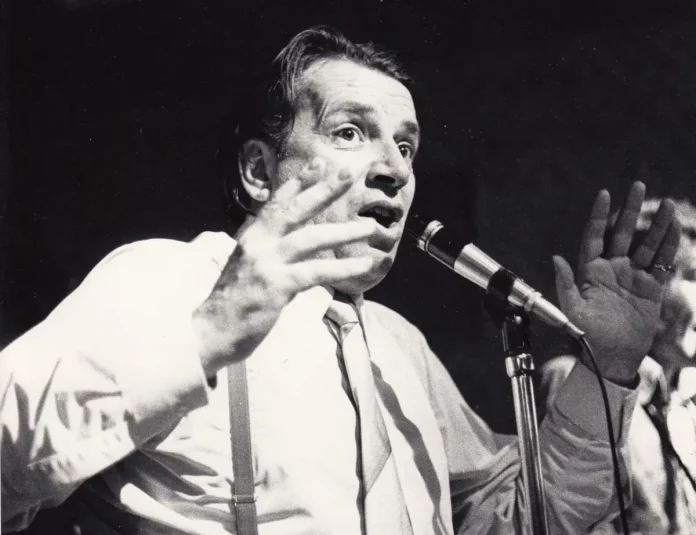

Let’s start with a good laugh. “Rocking Chair is marvellous too, perhaps the highlight of the record for me, where Melly’s voice matches the towering stature of Louis Armstrong in sheer charisma alone”. This comes from a new paperback, The Life and Work of George Melly (Wisdom Twins Books, £10.25), written by Chris Wade. Mr Wade, who didn’t ever meet George, has a distasteful style of writing. Listening to George’s records, “You can close your eyes, lay back and transport yourself back to another time… Or if that’s too pretentious for you, you can turn the record up to full volume, dance your bollocks off until you’re sweating like a mad chimp and do so until 7 a.m….

George was most notable for being a very good writer. If you want to read about him, read what he wrote about himself

His account of George’s records insists that they are great classics, whereas George was always rather shame-faced about their shortcomings, particularly the early ones. Mr Wade’s 160 pages have rounded up a mass of previously published trivia about the singer and also managed to regurgitate some of the most sickening anecdotes about George’s worst behaviour. There is at least one that, had it been me, I wouldn’t have been able to force myself to write down or even mention. Normally one would expect such material to be exposed only by someone who hated his subject.

Mr Wade hasn’t troubled to turn his interviews with Diana Melly and Wally Fawkes into prose, printing his questions and their answers without any polish or quotation marks. Sentences frequently begin with “So”, “Well”, and “Oh yeah”, and you get “It wasn’t my favourite sound, George’s voice. (Laughs)”.

Ha Ha. Non-fiction books normally have an index. This one doesn’t. There is a contents page listing 13 items, but with no page numbers given. Mr Wade’s jazz experience can perhaps be gauged by the subjects of his other books – The Kinks, Malcolm McDowell, Captain Beefheart and so on. His “comedic fiction” includes Cutey and the Sofaguard.

George was most notable for being a very good writer. If you want to read about him, read what he wrote about himself.

Stan Getz settled

“I’ve reached the eighth stage of my life”, Stan Getz said to Herb Ellis. “It’s time to settle my affairs. I’m going to call up and apologise to everyone I’ve ever upset”.

“I hope you’re not going to use a pay phone”, said Herb.

Stan must have been unhappy to read this newspaper report:

“A New York judge has denied a request by Monica Getz, the former wife of jazz saxophonist Stan Getz, to have his celebrity status considered marital property in their divorce. The judge said Get’z status was worth little because of his ill health. According to court papers, Getz, 60, suffers from liver cancer, lymphoma and cirrhosis of the liver. His doctor testified that Getz probably has two years to live”.

Jazz exclusion

As the major changes in jazz occurred there were those followers and sometimes musicians who fell by the wayside and couldn’t accept new thought in music. This was first brought home to me when Sinclair Traill and Max Jones of blessed memory managed over the final decades of their lives to exclude the music of Charlie Parker from their listening.

Oddly enough there are still listeners, including musicians, even today who have managed to lock Parker’s inventions out of their brains.

Back in the 50s the journalist Derek Jewell was asked to run evening courses on jazz appreciation. Derek, a gifted national journalist, was too busy and suggested the organisers approached me instead.

I took up the offer and the gig, with meetings across Lancashire, Cheshire and Merseyside, lasted me for more than 30 years.

Early on in the first programme (each course usually ran for about 24 meetings) I encountered the problem of introducing people to the charms of modern jazz. Some of those who attended were already well-versed in bop, but a majority weren’t. This hurdle had to be stepped over before we could go on. I found an easy way of doing it, and basically used just two titles from the same session – Norman Granz’s What Is This Thing Called Love and Funky Blues – as a painless but very lucid introduction. The set, called Charlie Parker Jam Session, produced a CD that runs for over an hour. As I write there are three second-hand ones on Amazon around the six quid mark. After them it’s £16 upwards.

Most people will already have or at least know of this session. Norman regarded improvised jazz as a priority. His Jazz At The Philharmonic units wore his heart not so much on its sleeve but through the hole blasted in the theatre roofs. In the earlier JATP concerts good taste was largely sacrificed to sound ravagers and their songs of the vulture.

But Funky Blues, the first of Norman’s studio jam sessions in July 1952, was a basic but profound 13-minute blues where none of Norman’s first 11 (10, actually) put a foot wrong.

“When the musicians I choose play for me”, Norman told me, “I want blood”.

In this session he didn’t ask for any, for the unique line-up showed great respect for each other. Charlie Shavers was on trumpet, Ben Webster and Flip Phillips on tenor and the sparks were to be struck by the three altos – Benny Carter, Johnny Hodges and Charlie Parker.

Kessel’s followed by Carter’s clean, beautifully formed display of what you can do with an alto. It’s almost wailing, but wailing with its hair combed

“I don’t recall any sense of rivalry at the date”, said Carter. “I wouldn’t say we felt pitted against each other, more like combined. It all went very smoothly. How else would it go with three so-called giants?”

What Is This Thing is a great tune for a jam session, as Peterson’s fine opening solo demonstrates. There’s good stuff from Shavers and Kessel. In between them comes Hodges improvising exquisitely on the melody, shifting emphases and re-sorting the theme in the timeless mainstream manner. Kessel’s followed by Carter’s clean, beautifully formed display of what you can do with an alto. It’s almost wailing, but wailing with its hair combed. Carter was a man then in a most interesting stylistic flux. Benny was one of those gifted musicians who arrived at the conclusions made by bebop without actually needing to listen to Diz and Bird. But he still kept his “swing” posture, simply dipping into modern devices of his own in the flow of his most inventive ideas. After Flip Phillips, Parker follows with a solo that is alive, wriggling like an eel, flying with an intensity that makes the backing irrelevant.

Funky Blues must be regarded as a jazz classic at least in regard to its three alto solos. With respect, most of the drama is here, and in contrast the contributions of Charlie Shavers, Ben and Flip fade rapidly from the memory. Only Peterson, with his vivid and profound solos, is in the class of the altos. It became the fashion to be blasé about Oscar, but at this time the 27-year-old’s work was still fresh to us on this side of the Atlantic.

Hodges, ever his own man, is eloquent with gorgeous authority. After a breath-stopping entry, Parker compresses some spikey ideas into his wonderful address. Here, modern as he is, his overall drive is simple timeless blues. It’s the latter that opens the eyes of new listeners to “modern” jazz and it’s the simplicity that dazzles, not the accompanying complex shards. Perhaps only in Benny’s choruses does one feel one’s being given a display. It’s perfect, but doesn’t have the emotive power of the other two. With the three men in such close proximity the power of emotion in the playing of Hodges and Parker is obvious, and Carter’s approach, acrobatic, measured and tidy, cannot live with that kind of competition.

Benny Carter

Carter is one of those musicians, like the pianist Billy Taylor or the clarinettist John La Porta, who are technically gifted to an extraordinary degree, but seem not to feel the need for much passion in their playing, And yet, with the style that he grew up with, he was easily capable of providing exciting jam session solos, as he does, for example, in the 1947 Just Jazz concert from Pasadena where he partners Wardell Gray in a swinging One O’Clock Jump.

Granz also had Willie Smith under contract at the time and it’s possible, but non-productive, to wonder what would have resulted if Willie had been there instead of Benny. Had Norman added Willie as a fourth alto, the overall symmetry would surely have been lost. Hodges and Parker were the two profound soloists. Willie was great for setting the stage on fire with JATP and wonderful with his driving swing in a small group, but he would have lacked the delicate phrasing of Bird and Rabbit. (Oddly enough, despite his tough and attacking style, Willie was a very nervous and highly superstitious man).

One can imagine Willie being used instead of Carter alongside Parker and Hodges, and I’m sure the setting would have produced an outstanding performance from him. Willie swung like mad and was a wailer, but Parker swung like mad and was a wailer and a genius of jazz as well. Willie is best tasted as a loner, where he excelled in such performances as Tuxedo Junction with Harry James, the jumping small group tracks on Keynote with Nat Cole and the various JATP performances to which he brought a higher class of wailing. The remarkable Tuxedo is on a wonderful Columbia CD, Snooty Fruity – Willie Smith with the Harry James Band. Very rare and you’d be luck to find a copy.

Carter, possibly the only one of the giants to record in every decade from the 20s to the end of the last century, was one of the most gifted of all jazz musicians. When he is described as a multi-instrumentalist one can assume that he could play anything. He was a natural, who chose the trumpet and the alto as his main voices, but of course was a brilliant arranger, who also put together a series of big bands to play what he had written.

Benny had a most interesting run-in with John Hammond, a man whose family ran over with money, quite a lot of which he poured into the promotion of Fletcher Henderson and Count Basie and their bands.

Farewell John Williams

Although he gave up professional work, pianist John Williams didn’t stop playing when he went to work at the Home Savings Bank and became, for 20 years, a city commissioner of Hollywood, Florida. In conversation, he always deprecated his playing from the 1950s as inadequate, an evaluation that flies in the face of the wisdom of his employers – Stan Getz, Bob Brookmeyer, Cannonball Adderley, Al Cohn and Zoot Sims amongst them – and of listeners who have been stimulated by his work for more than half a century.

John deprecated his playing from the 1950s as inadequate, an evaluation that flies in the face of the wisdom of his employers – Stan Getz, Bob Brookmeyer, Cannonball Adderley, Al Cohn and Zoot Sims amongst them

I’d first met and interviewed John at my home in Liverpool (he and his wife Mary took a taxi from Manchester airport) when he first holidayed in England. After the interview he and Mary took another taxi for 150 miles from Liverpool to North Yorkshire, to see the countryside wherein their favourite television series, about a Yorkshire vet, was recorded.

Some year later Jenny and I travelled (peasant class) to the Williams’s Florida home in Vero Beach to stay with them. The beautiful two-storey house stood in magnificent grounds, and the garden, full of orange trees, ran down into a lake that was four miles by four miles. The top floor was reached by a staircase from the garden, and it was here, self-contained, that Jenny and I stayed. Mary had filled the refrigerator and there were several bottles of fresh juice from the orange trees in the garden. During our stay I managed to get the over-modest John to play some jazz piano for me, and he proved as dextrous and swinging as ever. Thanks to John’s and Mary’s careful planning, we had the holiday of a lifetime.

In more recent years John and Mary, who had been childhood sweethearts before she became widowed some years after John’s first marriage had broken up, moved back north to Wilmington, South Carolina, where some of Mary’s family now live.

John first heard the tenor player Spike Robinson on a New Year’s Eve radio broadcast from Denver. John phoned Spike to tell him how good he had sounded, and subsequently booked him for the Florida Broadway Festival. The two remained close friends.

After he retired from the bank, John continued to play sporadically. Sometimes, when he felt the need to play jazz, he’d hire a bassist and drummer at his own expense and set up jam sessions. He played a few seasons of afternoons as solo pianist at a country club. This kept his hand in, so that when the call came for him to tour in Europe with Spike, he wasn’t rusty, although, despite what to me were several inspired performances, he still ran down his own playing. The two recorded a fine session for Alastair Robertson, The CTS Session (Hep 2087). I went with the quartet to Jersey where they played with great success. Tragedy struck when, on our return to London, Spike dropped Bill Crow off at his hotel, leaving his car unlocked for a moment outside the hotel. When he returned to it his tenor sax, which he’d had since 1948, and his luggage including all the CDs which he carried to sell at gigs, had been stolen. Spike cared for his music more than money and was never a wealthy man. This was a colossal blow, but the theft of his beloved horn was worst of all.

Williams made a stir when he appeared on radio as the subject of Marian McPartland’s Piano Jazz. Thousands of people who had wondered what had happened to him since he disappeared from New York in the 50s suddenly found out through this programme. Uniquely, in Marian’s solo-piano series, John hired and paid for his own bass player. Who better could he have found than Michael Moore? His choice of material for the programme was very refreshing, capped by a typically imaginative Crazy She Calls Me.

John had risen to the top in politics when he lived in Broadway, Florida, becoming deputy mayor of the city and, as a result of his intense love of animals and his care for their habitat conservation, had had the John Williams Park named in his honour. He was responsible for saving much of Florida’s east coast’s natural areas. His position enabled him to create and maintain for many years the Hollywood Jazz Festival, enabling him to play again with friends like Bob Brookmeyer, Frank Isola, Buddy De Franco and Spike Williams. He and Mary had married in 1991.

John kept his interest in politics aflame to power him through his retirement, and Florida newspapers were happy to print many thousands of words of his comments.

John died in Wilmington on 15 December as the result of a severe fall the day before. He had many such falls over the previous few years and they caused his final months to be dominated by severe pain. On the first of them, he broke his hip and complications in the hospital meant that he stayed there for almost a year. Ten days after his final discharge, he fell and broke the other hip. In December 2017 he had fallen again, breaking bones in his neck and his back. He recovered to the point that he could, intermittently and insecurely, use a walker.

A glance at the Williams discography reveals that a lot of his recordings remain unissued. His trios seem to have recorded more than was needed for an album. It’s perhaps a forlorn hope to have these tracks released. A shame, since I’m sure they will be filled with inspired piano playing.

Jordi Pujol collected 20 of those trio tracks for Fresh Sound FSR-CD 405 and there are another 10 tracks by a 1994 trio on Mitsuo Johfu’s Marshmallow label.

Read Steve Voce’s 1994 Jazz Journal interview with John Williams