This is a record by one of the greatest hot trumpeters in jazz; he plays his horn over a pounding rock beat which establishes a consistently feverish atmosphere, and varies the mood by calling on the services of several greatly talented musicians, whose individuality is subordinated to the overall design. In fact, my first impression when I played the album was that Miles is the only one who can be said to take a solo, and although closer listening has revealed this to be an oversimplification, there’s no doubt that Miles climbs above the surface of the music in a way that none of the others achieve, in a way they’re presumably not allowed to achieve. John McLaughlin seems to remain within the rhythm section even when he’s obviously soloing, in a way that’s utterly different from his role on ‘In A Silent Way’. Shorter is slightly more prominent, but Bennie Maupin, often playing sinuous lines like an arco bass, can almost be said to be a member of the rhythm section for much of the time.

And what a rhythm section! The weight of numbers has led critics to marvel at the depth of the album, to draw attention to the complex cross-currents, and to observe that you could listen for years and still not find all there is to find. I can accept this, but I also believe that it doesn’t matter at all. I think that Miles is using pianos and percussion instruments in sections as other composers might use saxophones or strings. And if you wouldn’t want to delineate precisely the role of a single sax in a Basie arrangement, or worry about the exact role of the first violin during the ensemble parts of a horn concerto, why is it necessary to work out what, for example, each of the four percussionists is doing on this record?

Ralph Gleason’s prose sleeve note is concerned to a large extent with weedy poetics, but he makes at least one memorable point; ‘if the art makes it we don’t need to know and if the art doesn’t make it knowing is the most useless thing in life.’ The question is, does the album make it?

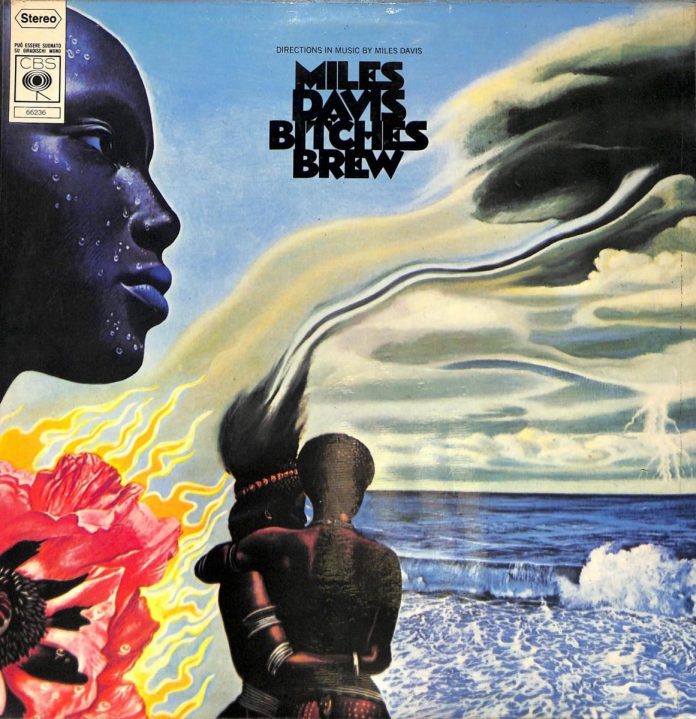

I think it does, but once again it’s a realisation that comes gradually; I’d lived with the records for at least a week before I got rid of my original notion that to employ such a rhythmic horde is a little like using an elephant to carry a brief-case. But it soon becomes obvious that the rhythm section is concerned with more than rhythm. Even during the album’s more reflective moments, there’s always some whispering from a drum-kit or one of the basses, some brief comments from the bass clarinet, or a faint interjection from a piano. This creates a most sinister effect which must be intentional; certainly the title track fits in perfectly with Mati Klarwein’s impressively horrific back-cover design, and might prove to be the ideal background music, if you like to do two things at once, for a reading of Edgar Allan Poe’s short stories.

Miles must have worked hard at getting all this together, and certainly the success he’s achieved in creating these superb backdrops has inspired him to great heights in his solo work. Bitches Brew is remarkable for his sparing but entirely effective use of the electric trumpet, most notably in the creation of a beautiful one-note ‘chord’ which makes its appearance several times during the out of tempo sections that open and close the piece. Miles Runs The Voodoo Down contains the most glorious stretches of trumpet, as Miles demonstrates his now complete mastery over his chosen medium of expression: without the aid of electricity, he makes his instrument sound at one moment like a trombone, at another like a tenor. Sanctuary is almost the odd one out, the gentlest cut on the LP, the backing handled mainly by subdued pianos, with the rock beat less prominent than at any other point on the record – nearly a ballad performance, in fact, though still smouldering as befits a part of the output from Miles’ hottest period – and he still hasn’t gone back to the use of a mute; maybe he realises it would melt.

It’s anybody’s guess whether or not a record like this will result in acceptance of Miles’ music by the kind of audience he’s trying to reach by appearing at this year’s Isle of Wight Festival; I just hope that it’s not going to put off those fans to whom anything connected with rock is anathema, because I believe that the stabbing, emotional jazz that Miles is playing in this fiercely contemporary context is an affirmation of the kind of values Satchmo himself would uphold.

Discography

(a) Pharoah’s Dance (20 min) – (b) Bitches Brew (27 min) – (a) Spanish Key; (c) John McLaughlin (21 min) – (c) Miles Runs The Voodoo Down; (b) Sanctuary (24 min)

(a) Miles Davis (tpt); Bennie Maupin (bs-clt): Wayne Shorter (sop); John McLaughlin (el-gtr); Chick Corea. Joe Zawinul, Larry Young (el-pno); Dave Holland (bs): Harvey Brooks (bs-gtr); Jack Dejohnette, Charles Alias, Lenny White (dm): Jim Riley (perc). (b) as for (a), minus Young. (c) as for (a), minus Zawinul.

(CBS 66236 2 record set 59s 11d)