No jazz autobiography has been more eagerly awaited than that of Miles Dewey Davis III, jazz music’s venerable Prince of Darkness, the highly durable cult figure who, after nearly half a century as a professional musician, still ranks as the world’s foremost jazz attraction.

Now, at last, the autobiography has arrived, one kilo and 432 pages of it – and, predictably, it sustains the iconoclastic, arrogant and extravagantly nonconformist image that Miles has assiduously cultivated throughout his working life. It also deals frankly with his relationships with women, his successful fight against drug addiction and the legendary musicians with whom he has played over the years.

It is curious that Miles Davis, who has made something of a religion out of style, should have produced a book that lacks it so comprehensively

It was in the summer of 1949, after returning from a spell in Paris, where he had an affair with Juliette Greco, that Miles Davis drifted into heroin addiction at the age of 23. ‘I wasn’t never into that trip that if you shot heroin you might be able to play like Bird . . . what got me strung out was the depression I felt when I got back to America. That and missing Juliette.’

Soon he was taking four or five capsules of heroin a day and the insidious drug began to wreak its havoc. ‘Shooting heroin changed my whole personality from being a nice, quiet, honest, caring person into someone who was the complete opposite,’ Miles says. ‘I started to get money from whores to feed and support my habit. I started to pimp for them, even before I realized what I was doing. I was what I used to call a “professional junkie”.’

He stole property from Clark Terry to pay for a fix and he began pawning his possessions, even his trumpet, to buy heroin. Miles battled against addiction for four years. Finally he resolved to kick the habit ‘cold turkey’. He locked himself in a room near his father’s house in East St Louis and went through the protracted agony of withdrawal.

‘The feeling is quite indescribable. All your joints get sore and stiff, but you can’t touch them because if you do you’ll scream . . . You feel like you could die and if somebody could guarantee that you would die in two seconds, then you would take it . . . This went on for about seven or eight days . . . Then one day it was over, just like that. Over. Finally over. I felt better, good and pure. I walked outside in the clean, sweet air over to my father’s house and when he saw me he had this big smile on his face and we hugged each other and cried. He knew that I had finally beat it.’

Later Miles became a cocaine addict, spending $500 a day on the drug at one point. But today, at 63, he neither drinks smokes nor uses drugs, ‘except the ones my doctor prescribes for my diabetes.’

The candid revelations about drink, drugs and the epic Davis sex life will no doubt make the book a best-seller; but the real value of the autobiography resides in the insight it provides into Miles’s creative processes and complex personality.

Miles’s earliest musical inspiration came from Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie. It was 1944, Miles was 18 and Parker and Gillespie were in the Billy Eckstine band which played a date in East St Louis. Says Miles, ‘I’ve come close to matching the feeling of that night in 1944 in music, when I first heard Dizz and Bird, but I’ve never quite got there.’

There is a fascinating background to Davis’s musical development and astonishingly prolific and innovative output – from the time he cut his musical teeth at Minton’s Playhouse in 1944 on through a dazzling series of hugely influential groups and seminal recordings.

One of the weaknesses of the book is its language; apart from a few passages where the work of the poet and teacher Quincy Troupe is evident, the text is simply transcribed from Miles’s taped recollections – and Miles is a long way from being as eloquent, witty and elegant a talker as he is a trumpet player. The pages are littered with the jazz musician’s favourite expletive and the undistilled, unfiltered, stream-of-consciousness delivery soon becomes wearying. It is curious that Miles Davis, who has made something of a religion out of style, should have produced a book that lacks it so comprehensively.

Notwithstanding the limitations of a language in which ‘shit’ describes practically everything, the book does provide pointers to Miles’s real character and the considerable gap that separates him from his public persona. In public, Miles radiates a kind of elegant malevolence, an insolent imperiousness; but in private, he is, like all of us, looking for something to hold on to.

Although he came from a prosperous, middle-class family – his father was a dental surgeon – Davis has suffered more than his fair share of adversity, some of it self-inflicted. Apart from the ravages of heroin and cocaine, he has been beaten up by the police, shot at, had operations on his throat and hip, suffered from an ulcerated stomach, diabetes, arthritis and sickle-cell anaemia and once broke both his ankles when he fell asleep at the wheel of his Lamborghini.

But through it all he has sustained his astonishing creative resourcefulness. Fellow trumpet player and writer Ian Carr has observed that Davis’s great achievement is that he has broken the monopoly of conventional musical thought decade after decade, causing people to ask, ‘Is it jazz?’, and then causing them to revise and expand their ideas of the music’s identity and possibilities.

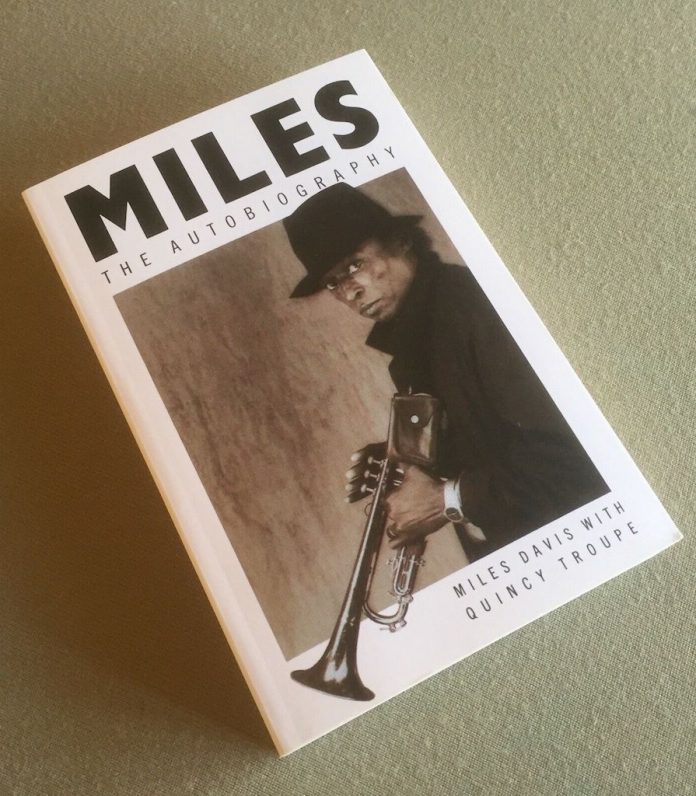

Miles – The Autobiography by Miles Davis with Quincy Troupe. Macmillan, hb, 426pp, £13.95