As many a fine musician in this country has found to his cost, there has until quite recently been a prejudice against British jazz players. Also, feelings towards anyone but an American Negro who tries to sing blues are still far from sympathetic. It is hardly surprising, therefore, that the critics’ attitudes towards the recent British blues boom has, apart from a few exceptions, been one of hostility.

Naturally, any lover of good jazz and blues must despise the fact that there exist bands of young men with the audacity to call themselves blues groups who have never heard of, let alone actually listened to records of, Kokomo Arnold (1). However, almost equally distressing but more understandable, is the attitude of blues fans who refuse to listen to any white musicians playing blues. More understandable, because there have certainly been some pretty bad attempts by whites at playing, and more particularly at singing, the blues. Distressing though, because these fans are denying themselves much listening pleasure and denying some fine musicians proper recognition.

“Peter Checkland and Derrick Stewart-Baxter have recently pointed out the tasteless, hideous results that can occur when middle-class British youths sing about their hard times in the cotton-fields, riding the blinds, and other experiences of the real bluesmen”

Blues is, musically speaking, several years behind jazz, and so too, I feel, are the attitudes of its devotees. Who would say today that jazz has to be played by U.S. Negros? We acknowledge an enormous debt, to them for formulating the language of jazz and, of course, providing so many great musicians, but we now know that one can be born almost anywhere, with any coloured skin, and play good jazz, if the musicianship and inclination are there.

This attitude has not yet reached the blues. The reason probably lies in the fact that the blues is essentially a vocal music, despite any instrumental interest that may be present. Peter Checkland (2) and Derrick Stewart-Baxter (3) have recently pointed out the tasteless, hideous results that can occur when middle-class British youths sing about their hard times in the cotton-fields, riding the blinds, and other experiences of the real bluesmen, which could not be further removed from life in suburban England. How can a blues lover be expected to respond warmly to such false emotion? Such singers have not appreciated the difference between imitation and emulation: between copying exact lines and vocal tones of their bluesmen heroes, and getting to grips with the essence of the blues and then projecting their own message within the blues idiom. In the last few years, however, there has been a growing number of white Britons who have appreciated this difference and its importance, and they are making some pretty interesting sounds.

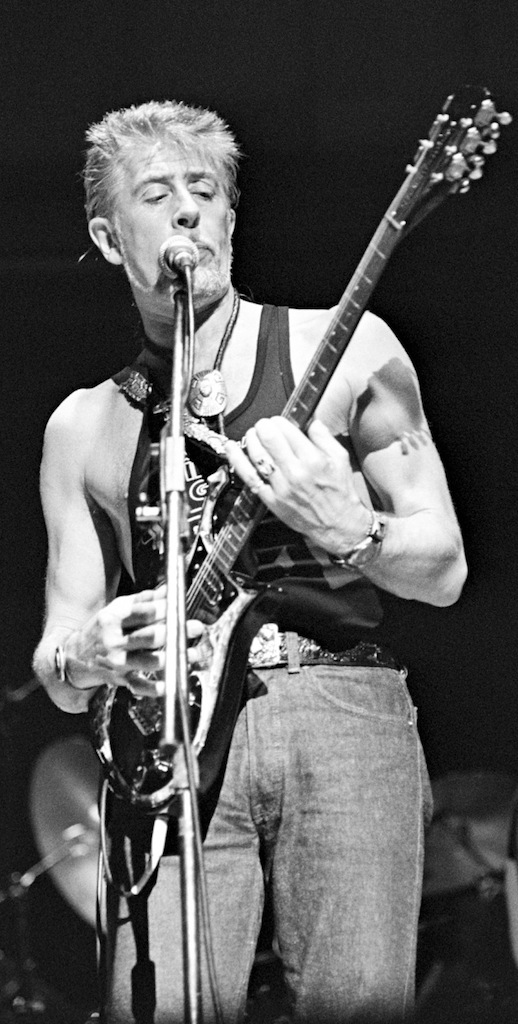

One such is John Mayall. It has been said that Mayall does not possess a blues voice (4), but he sings without affectation, powerfully in his upper range, warmly in his lower, but always convincingly. He began by performing versions of well-known blues songs and his own compositions. His interpretations of blues standards (such as Dust My Blues, Parchman Farm, You Don’t Love Me) stuck close to the originals without ever becoming slavish imitations. On his album ‘Crusade’ (1967) his ability to maintain the essence of a particular blues, yet still sound original, was shown to full advantage – particularly on Sonny Boy Williamson’s Checkin’ On My Baby, which features an extended harmonica solo by Mayall which builds to a tremendous climax where the harp is wailing almost like a soprano sax.

His own songs sound fresh and convincing, largely because he is singing about his own experiences. John’s latest LPs (‘Bare Wires’ and ‘Blues from Laurel Canyon’) have featured solely his own numbers. On ‘Laurel Canyon’ and the first side of ‘Bare Wires’, the pieces are connected both by subject matter and by musical linkages – there are no breaks between the tracks, everything being woven into one continuous suite.

It was Eric Clapton’s guitar work with the original Bluesbreakers that gave the sound and the style to all contemporary British blues and much of today’s pop music

John’s instrumental abilities extend to several instruments – organ, piano, harmonica, various guitars (such as 5 and 9-strings), and he has also dabbled on harpsichord and harmonium. He is not, however, a virtuoso on any of these, but has a good bandleading ability and has been able to leave the pyrotechnics to his sidemen, notably the lead guitarists. It was Eric Clapton’s guitar work with the original Bluesbreakers that gave the sound and the style to all contemporary British blues and much of today’s pop music.

The heavily amplified B. B. King-like phrases that Clapton used though, have now been done to death by a whole host of second-rate imitators: King, and Clapton too, had something to say, and used their style of playing to say it. For too many aspiring guitarists now, the message seems to be the medium, and their frantic attempts ring hollow. It is interesting to notice that Mayall’s present group has no lead guitarist, the line-up being Mayall (who seems now to be concentrating almost entirely on harmonica, and vocals of course), Johnny Almond (tenor and alto saxes, and flute), John Mark (acoustic rhythm guitar) and Stephen Thompson (bass guitar). Note too the absence of a drummer. Despite (or possibly because!) of the absence of what have been the two most prominent instruments in modern blues, the group generates a nice easy-going swing with plenty of room left for solos (particularly from Almond). This sound could possibly be the prototype of a new generation of British blues, as Mayall’s first Bluesbreakers were three or four years ago. This though is purely personal speculation.

To return to the present and the recent past I think it is fair to say that the sudden flowering of British blues is almost entirely the work of one man, namely John Mayall. Pop audiences had been introduced to the blues via rock ’n’ roll by such groups as The Beatles and The Rolling Stones in the early sixties, but by 1966 (the year when the Mayall/Clapton Blues-breakers LP was issued) these groups had left their earthier backgrounds far behind and were concentrating almost entirely on ‘recording studio’ music: music whose lifeblood was special sound effects created in the studio and which could not be reproduced ‘live’. This emphasis on recording rather than performing led to a low standard of live musicianship – particularly from groups who used studio musicians ‘en masse’ on their records because they ‘couldn’t learn the tune in time for the recording date’. Suddenly Mayall’s quartet appeared on the scene, impressing everyone with their musicianship, their power and their ability to communicate real blues.

Theoretically, the Cream appeared to be aiming for the same goals as the Ornette Coleman Trio: i.e. collective free improvisation of a lead voice (alto-sax with Coleman, guitar with Cream), bass voice (double-bass with Coleman, bass guitar with Cream) and drums

Later in 1966, Eric Clapton left the Bluesbreakers. Mayall took on Peter Green and the group continued in much the same vein. Clapton, however, teamed up with bass guitarist Jack Bruce and drummer Ginger Baker to form the all-star virtuoso group entitled, perhaps somewhat arrogantly, The Cream. The policy of this group was much looser than Mayall’s. Instead of a soloist taking a couple of choruses between vocal verses, the Cream developed much freer techniques of improvising, individually and collectively. To observe the difference, it is interesting to see how the two groups attempted a Robert Johnson blues. Clapton sang Rambling On My Mind with Mayall and the number turned out similar in spirit, though somewhat different in sound, to Johnson’s original. Crossroads by the Cream, however, became a completely new piece, and is merely treated as a vehicle for extended improvisations. Theoretically, the Cream appeared to be aiming for the same goals as the Ornette Coleman Trio: i.e. collective free improvisation of a lead voice (alto-sax with Coleman, guitar with Cream), bass voice (double-bass with Coleman, bass guitar with Cream) and drums. In practice, however, their music, although a new experience to the pop world, often seemed to fall short of their aims, there being many times when they found themselves playing tired clichés. Much of their music fell outside the blues field, but they are important nevertheless for showing the possibilities that increased freedom could give to blues musicians.

Around 1967-68 new groups were springing up at an amazing rate. Ten Years After were a foursome whose virtuosity surpassed even the Cream. Unlike the Cream though, they usually kept their improvisations within the more conventional limitations of the blues chord sequences. This led to some exciting blues playing, but did tend to reduce all numbers to a mere display of virtuosity. As with all music, virtuosity for its own sake can stagger initially, but soon becomes boring. Ten Years After are still playing brilliantly and continue to maintain their initial fervour, but to gain the respect of bluesmen they should re-examine the content of their material.

Someone who was reconsidering his musical philosophy in 1967 was Peter Green, the guitarist who replaced Clapton in the Bluesbreakers. It appears that Green, like his predecessor, also became frustrated by the straightjacket imposed by Mayall. However, once freed from it he failed much more disastrously than Clapton. He teamed up with Jeremy Spencer, a bottleneck guitarist who found his inspiration in Elmore James. About half the output of Peter Green’s Fleetwood Mac consisted of close Elmore James imitations with Spencer’s straining voice and slide guitar featuring prominently. The other half was made up of numbers by Green. These tended to be of the loose form favoured by John Lee Hooker: not so much songs as a string of vocal and musical phrases which flow on from one idea to the next.

Such a technique requires inspiration and a high level of creativity to come over effectively (possibly the best examples on record are Hooker’s LPs ‘Live at the Cafe Au Go Go’ here he uses this method of singing in front of Muddy Waters’ Band, and ‘How Long Blues’ where he is performing on his own), but when this is lacking, the results can be extremely boring, giving the listener the impression that he is merely being presented with a list of all the blues clichés ever invented. Unfortunately, Green was rarely inspired and so the results are somewhat tedious. To prevent his audiences from becoming too bored, Green has recently started to introduced some rock ’n’ roll into his repertoire, and the surface excitement of these numbers has caused the group to become favourites with the pop audiences. He has also written some simple instrumentals (such as his hit-parade success Albatross) which wouldn’t have sounded out of place if the Shadows had played them note-for-note ten years ago. No wonder that British blues is having a hard struggle for recognition!

The vocal screams, swoops, groans and cries of Led Zeppelin may have a sort of hideous fascination, but the authority and dignity that comes from the bluesman’s experience can get a message across that no amount of frantic overstatement can achieve

A trio named Led Zeppelin are the antithesis of Fleetwood Mac. Their sound is urgent, compelling and vital. It is a sad but undeniable fact that blues is a dying art for the American Negro: the older artists have lost their initial impetus (happily there are still a few exceptions), while many of the younger generation are turning to soul music. Reviewing a blues concert at the Festival Hall last autumn, Miles Kingston wrote in The Times (5): ‘The most interesting thing … was the contrast between the authentic article provided by Muddy Waters’ Blues Band and Champion Jack Dupree … and the British version as interpreted by John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers and Aynsley Dunbar’s Retaliation. Interesting because one could almost say that the British musicians are more involved in the blues than their American counterparts. By this I mean that whereas the Americans seemed to go through a routine, the British players not only threw themselves violently into their music but had the talent to bring it off – their guitar playing was by far the best of the evening and a splendid very slow blues by Dunbar’s group sustained its mood in a way that the Americans never really tried to rival.’ Led Zeppelin are in this class. Their music is a physical assault, and to listen to their LP, even at a low decibel level, is a completely exhausting experience. The tension hardly eases up for a minute: as soon as one track ends the next is beginning – in one place there is even an overlap. The instrumental work is on a very high level, but the singing leaves something to be desired. To return to Mr. Kington’s review (6): ‘And yet there is still something dogged and earnest about the British blues which is not quite convincing; they try too hard, play too loud to be natural.’

This ‘trying too hard’ is particularly noticeable with the singers. Muddy Waters recently said (7): ‘(White boys) can play the blues better than me, but they’ll never be able to sing them as good as me.’ This really is the essence of the matter. The vocal screams, swoops, groans and cries of Led Zeppelin may have a sort of hideous fascination, but the authority and dignity that comes from the bluesman’s experience can get a message across that no amount of frantic overstatement can achieve.

There are many other groups that have produced interesting music, notably Keef Hartley’s Band (which enjoys the benefit of Henry Lowther’s trumpet and violin playing and some attractive arrangements), Jethro Tull, Love Sculpture and Jon Hiseman’s Colosseum, but I chose to concentrate on those who have been the most influential or who are most likely be of interest to jazz and blues lovers.

In the final analysis, these musicians are to be congratulated for keeping the blues tradition alive and introducing the real article to a number of pop fans. Brave attempts have been made, but the real essence of blues has rarely been completely caught. But there’s time yet.

References:

(1) Steve Voce: ‘Salty Dog’, from ‘It Don’t Mean A Thing’, Jazz Journal, January 1969.

(2) Peter Checkland: ‘Substance and Shadows’, Jazz Journal, July 1969.

(3) Derrick Stewart-Baxter: ‘Black London Blues’, Jazz Journal, August 1969.

(4) ‘Crusade’ LP review, Jazz Journal, October 1967.

(5) Miles Kington, The Times, date unknown, 1969.

(6) ibid

(7) Don DeMichael, Paul Butterfield and Muddy Waters conversation: Downbeat, July 1969.