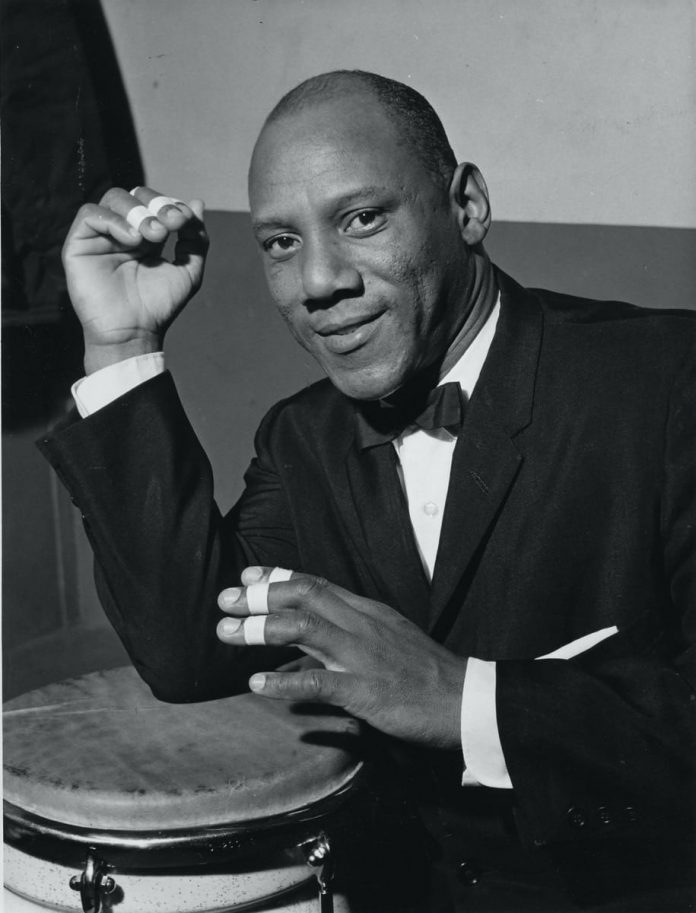

Cuban-born percussionist Cándido Camero (usually simply known as “Cándido”), died at his home in New York City on 7 November. He was 99. He was called the “father of modern conga drumming”, and his innovation was to play more than one conga drum at a time, sometimes adding bongos. He thus achieved an effect not unlike a pianist playing chords with his left hand, while using the right to play the melody with added improvised embellishments – a phenomenon sometimes termed coordinated independence.

He also invented a device which enabled him to play a cowbell with one foot. As his friend and fellow percussionist Bobby Sanabria said at his memorial service, “When you talk about percussion, particularly the evolution of conga playing, you’re talking about two periods – before Cándido and after Cándido.”

Encouraged by Dizzy Gillespie, he first visited the US on a tour in 1946, and appeared at a Broadway theatre in the musical revue Tidbits, performing with two Cuban dancers while he played (and introduced) the quinto, a drum with a higher pitch than the standard conga.

In 1952 he settled permanently in New York and began appearing and recording with the Billy Taylor trio (1953-4), and the orchestras of Dizzy Gillespie (1952) and Stan Kenton (1954). Taylor asserted “I’ve not heard anyone who even approaches the wonderful balance between jazz and Cuban elements that Cándido demonstrates.”

Other American jazz musicians obviously agreed, and over the years Cándido recorded with such luminaries as Al Cohn (Cándido Featuring Al Cohn, 1956), Art Blakey (Drum Suite, 1957), Ray Bryant (Ray Bryant Trio, 1956), Kenny Burrell (Introducing Kenny Burrell, 1956), Duke Ellington (A Drum Is A Woman, 1956), Erroll Garner (Mambo Moves Garner, 1954), Dizzy Gillespie (Gillespiana, 1960), Coleman Hawkins (The Hawk Talks, 1955), Stan Kenton (Kenton Showcase, 1954), and Wes Montgomery (Bumpin’, 1965). His albums as leader include Cándido (1956), The Conga Kings (2000) and Hands Of Fire (2008). He also made regular TV appearances, on The Ed Sullivan Show and The Jackie Gleason Show.

Cándido Camero Guerra was born 22 April 1921, near Havana. His father worked in a bottle factory, and his mother worked at home. Encouraged by an uncle who taught him (at the age of four) to play “bongos” on two old cans of condensed milk, he quickly progressed to the bass, piano and tres, the latter the small Cuban guitar, but he never learned to read music. Listening on the radio to American jazz, he was impressed by drummers Kenny Clarke and Max Roach, but was mainly influenced by Spanish and Yoruba music.

After he became a working musician at the age of 14, his father would smell his breath after he came home and command “Say ha.” When Cándido said “Ha, ha” his parent would reply “Only one is needed. One is enough” because he could easily tell if Cándido had been smoking or drinking. To the end of his life, Cándido refused to indulge in drugs. He explained in 2005 “I saw what drugs did to Charlie Parker … what they did to Billie Holiday, a woman with so much talent but with so many insecurities. I’ve been on buses with musicians smoking dope and drinking. False inspiration, I always called it.”

Twice married and with two children, Cándido continued to perform into his mid-90s. When he appeared in a guest performance at Birdland in 1999, Peter Watrous, the New York Times critic, reported: “Mr Camero has access to the divine, and when he began to play, the music changed. He uses several tuned conga drums and he began by playing melodies carefully. His playing makes sense, it has cadences and it starts and finishes logically. And he swings.”

The true measure of Cándido’s musical achievements, aptly described by musicologist Raul A. Fernandez, was in “establishing the conga drum as an integral, if not essential, component of the modern straight-ahead jazz percussion scheme and securing a place for the ‘Latin tinge’ among the many rhythmic tinges available to the modern jazz drummer.”

Among his many awards were his designation as a Jazz Master by The National Endowment for the Arts (2008), and a Latin Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award (2009). On receiving the NEA honour he said it was like “seeing an impossible dream come true. I thank the NEA and the United States of America.”