George Wein, once characterised by the New Yorker’s Lillian Ross as a man “who seemed to be filled with controlled frenzy”, was a music producer, founder of the Newport Jazz and Folk Festivals, pianist, impresario and autobiographer. He died at his New York City apartment on 13 September aged 95.

During his long, productive and eventful lifetime, he received plaudits from jazz critics and fellow musicians. Duke Ellington, in his autobiography Music Is My Mistress wrote that Wein (pronounced ween) “has made a tremendous contribution to the welfare of all of us who fight under the banner of jazz. Personally, he is one of the good guys, and no matter how successful he is in business, he still likes to sit down at the piano and open up his left hand”.

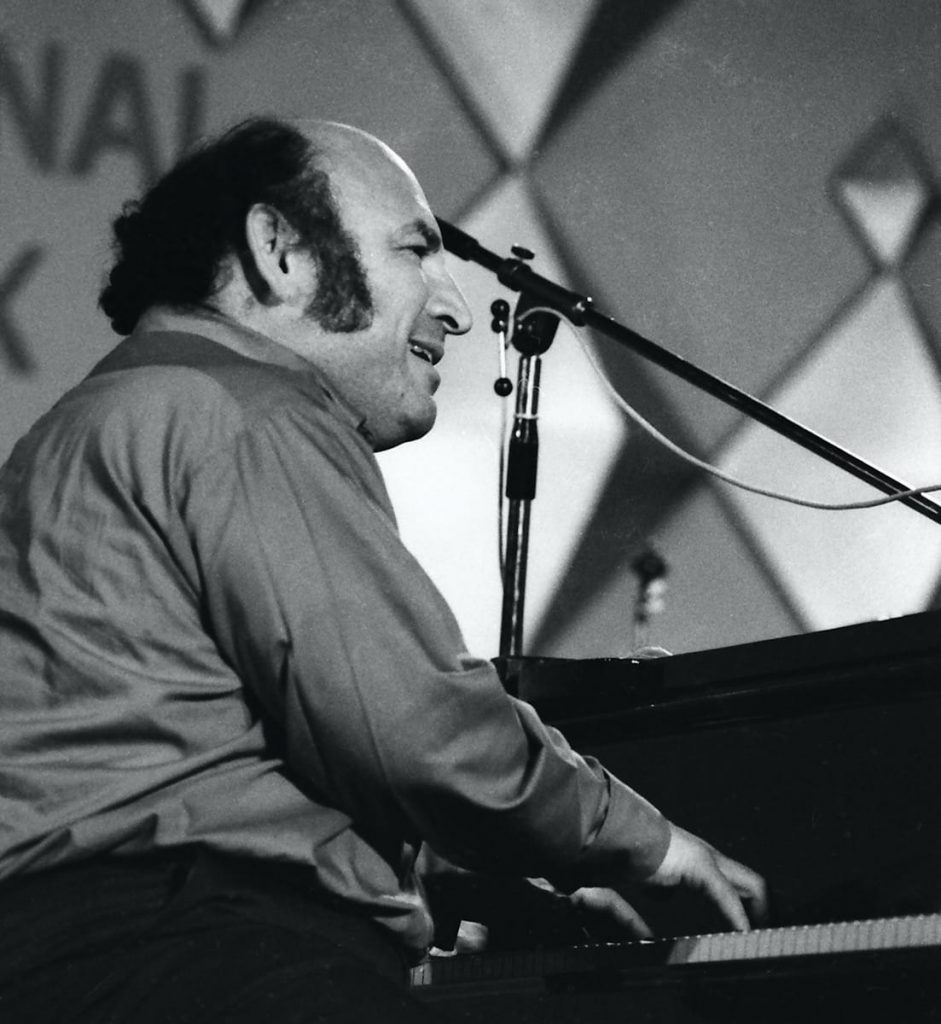

Modest about his pianistic skill, he was a more than competent jazz musician, and made over 12 LP albums, with variously named groups. He was initially taught piano by Margaret Chaloff, mother of baritone saxophonist Serge Chaloff and his jazz hero was Teddy Wilson, with whom he studied briefly. When he played with Ruby Braff, Pee Wee Russell, and Buzzy Drootin at the Newport Jazz Festival in 1960, Dan Morgenstern noted that Wein had been unfairly (but understandably) criticised. “It’s easy to see why – there aren’t many people on his side of the jazz fence who play an instrument well enough to appear on the other side as well. He is not much more than competent, but competent he is.”

Morgenstern added that it was high time to “forget about his other roles” – particularly “the accusations levelled against Wein by Messrs Mingus and Roach in re Jim Crow [as] just so much hogwash” – an oblique reference to their “rebel” breakaway appearances at the 1960 NJF over his allegedly overly commercial booking policy. Nat Hentoff, who in 1959 had branded the NJF as a “sideshow”, capitulated in 2001 when he conceded that Wein had “expanded the audience for jazz more than any other promoter in the music’s history”.

It was the success of his Boston nightclub, Storyville, named after the New Orleans red-light district, that prompted Elaine Lorillard, a rich Bostonian and Newport resident, to invite Wein to produce what became the first NJF. With the financial support of her husband, heir to a tobacco fortune, who offered a $20,000 donation, Wein’s subsequent career was set. As one critic, Gene Santoro noted in 2003, without Wein’s input “everything from Woodstock to Jazz at Lincoln Center might have happened differently – if it happened at all”.

Wein’s greatest achievement was to take jazz out of smoky night clubs and into the more healthy open air – not only at Newport but also in Paris, Nice, Warsaw and other overseas venues, as well as across the United States, where he also produced the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival, and helped Hugh Heffner launch the Playboy Jazz Festival in Los Angeles. His only competitor in these enterprises was Norman Granz and his worldwide Jazz At The Philharmonic (JATP) extravaganzas and recordings.

Many of Wein’s early ventures were less than successful. He estimated that the inaugural NJF, despite massive attendances and the attention of the news media, barely broke even. By his later calculations, it made a profit of $142.50 – and only because he waived his $5,000 production fee.

His happier memory was that he had arranged a reunion between Lester Young and Billie Holiday – who had not spoken for years. Pres seemed reluctant to appear on stage with her, but Wein reported that after about three choruses of the first song Pres said: “I guess I’ll have to go and help the Lady out.”

Wein hit on the idea of corporate sponsorship: ‘I never realized that you could make money until sponsors came along’

Wein then hit on the idea of corporate sponsorship for his festivals and tours, including Schlitz (beer), Kool (cigarettes), and JVC (Japanese electronics). Other sponsors of his Festival Productions events included Ben & Jerry’s and Dunkin’ Donuts. He told the New York Times in 2004: “I never realized that you could make money until sponsors came along.”

In 1972 he moved the NJF to New York City, with performances at Carnegie Hall, Radio City Music Hall and Lincoln Center. With various titles and sponsors, it thrived for 40 years. In 1981 the jazz festival returned to Newport, as did the folk festival in 1985. The festivals led to movies and concert albums, including Jazz On A Summer’s Day (with Wein obviously immersed in the proceedings) and Murray Lerner’s Oscar-nominated 1967 documentary Festival! featuring Bob Dylan, Johnny Cash and Howlin’ Wolf.

In 2005, having sold Festival Productions Inc to Festival Network LLC, he assumed a more limited role. Wein told the Associated Press in 2005: “I want the festivals to go on forever. With me it’s not a matter of business. This is my life.” He then set up the non-profit Newport Festivals Foundation to oversee its summertime events. In a 2018 interview, he said: “People say to me, you’re a businessman. I say I know how to add and subtract.”

George Theodore Wein was born 3 October 1925, in Lynn, Massachusetts and grew up in nearby Newton. His father, Barnet, was a physician and his mother, Ruth, an amateur pianist. His parents encouraged his early interest in music, and he began to consider a career in jazz. After serving in the US Army from 1944 to 1946 (with service in Europe), he enrolled at Boston University, graduating with a degree in history in 1950, by which time he was working as a pianist in and around Boston. In 1959 he married Joyce Alexander, a bio-chemist of African-American descent. After her death in 2005 he remembered: ”We could have been put in jail in 25 states when we got married, but in Boston we never had a problem. In 2002 they donated one million dollars to Boston University to endow the George and Joyce Wein Chair in African-American Studies.

Wein received many honours and awards for his services to jazz, including France’s Legion d’honneur and appointment as a Commander of Arts and Literature. Two American presidents – Jimmy Carter in 1978 and Bill Clinton in 1993 – invited him to perform at the White House. In 2005 he was named a Jazz Master by the National Endowment for the Arts. He received honorary degrees from the Berklee College of Music and Rhode Island College of Music, and was a lifetime Honorary Trustee of Carnegie Hall. His extensive discography includes George Wein (Atlantic, 1955), Wein, Women And Song (Arbors, 1955), Newport Jazz Festival All-Stars (Atlantic, 1959), Tribute To Duke (MPS, 1969) and Tribute To Count Basie (RCA, 1974).

His co-written (with Nate Chinen) autobiography, Myself Among Others: A Life In Music (2003), was voted the best book about jazz by the Jazz Journalists Association. In over 500 densely-packed pages of sometimes repetitious or florid prose, he offers some rueful reflections on his varied activities and vignettes of his favourite artists including Ella Fitzgerald, Dinah Washington, Sarah Vaughan, Frank Sinatra and Bob Dylan. His highest praises are reserved for John Hammond (the patrician record producer who “discovered” Billie Holiday and Count Basie and helped Wein when he was in financial difficulties), Duke Ellington (whose career he helped relaunch at the 1956 NJF) and, above all, Louis Armstrong. When Louis made a surprise appearance at Storyville, shortly after it opened, Wein recalled that this event “forever changed my life. I knew that I had to be part of his world”. He also discourses on Miles Davis’s sickle cell anaemia and cocaine addiction, and his falling out with George Avakian over the latter’s failure to include him as musical director in the list of credits for Jazz On A Summer’s Day. “I literally could not bring myself to believe that they had cited Avakian for musical direction – when I produced every minute of music on that stage. It was an insult. I left that theatre livid.” One press review not unfairly called the book “a sprawling mix of biography, anecdote, philosophy, hard-won lessons and musical history”. It might have added that it was also compulsively readable.

Wynton Marsalis accurately summed up Wein’s significance and character: “As a young pianist and club owner, he understood quality, worshipped the giants of the music, and created a revolutionary Festival [sic] format that offered the widest range of jazz to much larger outdoor audiences.” He added that Wein “loved telling stories about Bird, Duke and all of the greats, engaging in spirited debates on a variety of subjects, and was an optimistic supporter of young talent”.

In his autobiography, Wein confessed “It’s just by accident that I became a jazz producer. In the long run, it’s the music. I call that the raison d’être. That’s why I’m here”.

In September 2021, Jazz Journal republished George Wein – In My Opinion from JJ September 1961.