“The times I played solely bebop, it was my sole way of starving”. So philosophised Laurie Morgan, drummer and herald of modern jazz, who passed away on 5 February.

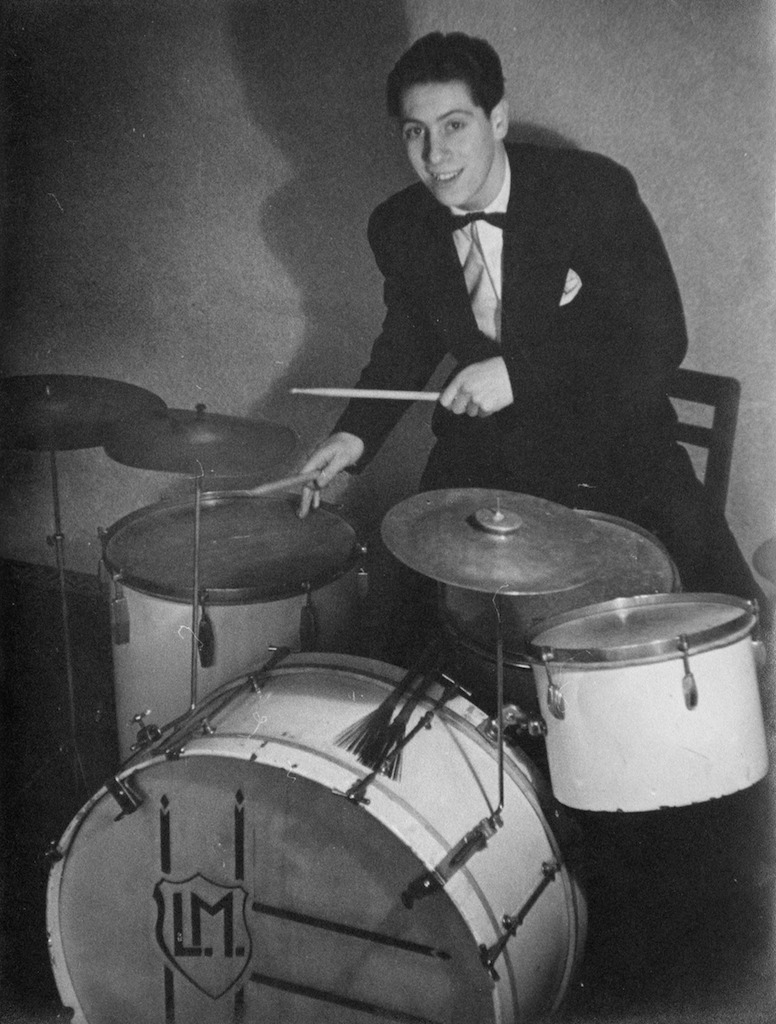

Laurie was born in 1926 to Jewish parents in Stoke Newington. When he was 10 and living in suburban Southgate his dad bought him a drum kit. By 1940, Don Rendell – his sax held together with rubber bands – and pianist Denny Termer were visitors. The teen trio jammed in the parlour; Laurie’s mum made tea.

In 1941, guitarist Stan Watson joined to form a variety quartet, The Rhythm Racketeers. With established musicians now conscripted or playing for troops, the West End opened up.

Soon 15-year-old Laurie was keeping immaculate time on show tunes and dance numbers at The Orchid Room, London’s ritziest nightclub. Then he worked US forces bases, accompanying the live act of perhaps the world’s number-one star, Jimmy Cagney.

In 1947, on the cloakroom record player at Old Compton Street’s Fullado Club, Laurie first heard Charlie Parker. “It was a clarion call”, he said. Aged 21, he flew to New York, becoming the first British jazzman to witness Bird and Dizzy Gillespie live. At 52nd Street clubs, the drummer got close enough to talk to his new idols.

Laurie bussed it to California, wandered Yosemite National Park, and communed with West Coast college boppers. In Los Angeles, he stayed with movie juggler Val Setz, whom he’d met doing the US camp shows. Laurie then returned to New York, and home on the Queen Mary.

From Ray Nance’s House of Note record store he had bought impossible to get bebop 78s. Hearing these discs became manna for London’s aspiring modernists.

He also shipped a trunk full of the latest Hollywood fashions for men, a gift from Setz. Other Soho musicians loved these clothes, so from their own American travels shipped back more. It was a sure influence on London’s first generation of male boutiques, such as Cecil Gee.

In 1948, Laurie and confederates started working out bebop for themselves at Mack’s Rehearsal Room in Great Windmill Street. Sessions drew audiences, so the musicians started charging. Club Eleven, Britain’s first modern-jazz club, was born. Laurie propelled Johnny Dankworth’s group; Ronnie Scott’s men, plus guests, shared the bill.

Here, in 1949, Benny Goodman’s pianist, Teddy Wilson, scouted Laurie to play London Palladium and possible European shows with the King of Swing. “Teddy chose me because I wore a beret and sunglasses”, laughed Laurie.

“He thought I looked the typical modernist, and wanted some of that in the show. In fact, I was disguising a head injury I got diving into the Serpentine!” However, the Musician’s Union stopped the 22-year-old drummer playing as his dues had lapsed.

In the 1950s, Laurie formed his Elevated Music ensemble with pianist Stan Tracey, which toured Europe. He introduced new Jamaican altoist Joe Harriott to London’s scene, and drummed in bands led by Leon Roy, Harry Hayes, Ambrose and Dizzy Reece. Starting that decade and for the next three, Laurie played small gigs with Club Eleven’s bebop decoder, pianist Denis Rose.

Laurie experimented and pioneered. Around 1960, he joined the collective playing Chelsea’s Café des Artistes. This included Beat poets Mike Horovitz and Pete Brown plus jazzers Tracey, Bobby Wellins and Dick Heckstall-Smith and future blues players, Alexis Korner, Graham Bond and Ginger Baker. Their New Departures happenings mixed improvised jazz and poetry, and toured colleges and jazz festivals.

Laurie wanted a jazz that could speak the true British experience, evoking its places and history. In 1961, with tenorist Wellins, he composed ethereal Culloden, foreshadowing Tracey’s Under Milk Wood suite.

At the nascent National Theatre, from 1964 to 1976, Laurie was resident percussionist and then assistant musical director. He worked on classic and avant-garde accompaniments for shows helmed by Sir Laurence Olivier and Franco Zeffirelli. A natural showman, Laurie often appeared on the stage, a drummer in a Shakespearean army or costumed band. He loved and learnt the Bard.

At home, in the 70s, when the local flats had problems with its bored adolescents, Laurie helped turn the empty house opposite into a community centre. Here, and later in London schools, he taught music.

From 1975-2000, Laurie played with Guyanese pianist Iggy Quayle and Jamaican bass player Coleridge Goode. An institution of the jazz underground, the Iggy Quayle Trio anchored all-comers sessions at Dingwalls in Camden, where punk-violinist Nigel Kennedy was one to join the jams, and at Finsbury Park’s Stapleton Tavern.

In the 80s, they managed their own Sunday-afternoon residency at a north London bowling club. Gigs were mini-festivals, family picnics and games spilling onto the grass. They then moved to The Kings Head, Crouch End. Here the trio, then Laurie and son Paul, held the spot for 35 years.

Laurie met Betty at Club 11 in 1949. The two married in 1954, had three kids, and were together forever more. In 2012, the couple retired to Sussex, where Laurie loved to watch the robins, tits, doves, pigeons and pheasants visiting his garden. This bird is free…

Later this year there will be a celebration in London of Laurie Morgan’s life and work. Those interested in attending should email sfmorgan@btinternet.com for details.