Writing in the 1920s, and most likely aware of only the most diluted and commercial forms of jazz, Sufi Inayat Khan declared his belief (in the book Music) that jazz ‘does not trouble the soul to think of spiritual things; does not trouble the heart to feel deeply.’ Had he lived long enough, one wonders what Khan might have made of the extraordinary range of spiritually potent music which Keith Jarrett has committed to record over the past 25 years – music which has been partly inspired, ironically enough, by Sufi ideas of inspiration and ecstasy.

This first full length study of Jarrett is distinguished by the same qualities that made Ian Carr’s previous monograph on Miles Davis such an enjoyable and valuable document. Close biographical focus is interwoven with a broad sociological perspective, and musical analysis delivered in reader-friendly but penetrating style. Musicians such as Jack DeJohnette, Gary Peacock and Jan Garbarek and ECM producer Manfred Eicher complement Jarrett’s own reflections, which range from highly specific observations on the jazz life to quasi-philosophical ruminations on the nature of musical communication.

The author has something fresh to say about all aspects of Jarrett’s career, from the early days with Art Blakey, Charles Lloyd and Davis right through to the classical recordings and the superb Standards trio of recent years. He is particularly good on the outstanding Belonging quartet (with Scandinavians Garbarek, Danielsson and Christensen) of the mid to late 1970s, offering some astute points of comparison with Jarrett’s other great quartet of the time, featuring Americans Redman, Haden and Motian. (Curiously, Carr eschews any mention of either Prayer, Jarrett’s exemplary duet with Haden from the 1974 Death And The Flower release, or the thematic relation of Great Bird, from the same release, to the much longer Survivor’s Suite ECM session from 1976, analysed in some detail).

Jarrett’s search for what he calls the state of musical ecstasy, or trance – whereby the flow of improvisation comes from the deepest layers of the self, rather than ‘off the top of the head’ – has often yielded great rewards. However, it has also brought him periods of uncertainty and depression. One of the most revealing parts of the book is the lengthy study of Spirits, the double LP which Jarrett recorded at his home studio, playing a variety of folk instruments: coming from somewhere deep in his unconscious, the music healed him of a particularly paralysing depression. (Jarrett’s relation to such 19th century American transcendentalists as Thoreau and Emerson becomes apparent enough here, as elsewhere, although the connection is not examined by Carr.)

Like Jarrett, Carr sees music as part of the totality of life, and in a closely argued final chapter, shows little patience with critics who have tried to diminish Jarrett’s importance with one small-minded adjective or another. As Carr suggests, not the least aspect of Jarrett’s multi-faceted achievement has been his refutation of both reductive critical pigeon-holing and outmoded ideas of ‘high’ and ‘low’ art. It is an achievement which has long merited the sort of diligently researched, enthusiastic appraisal which Carr offers here.

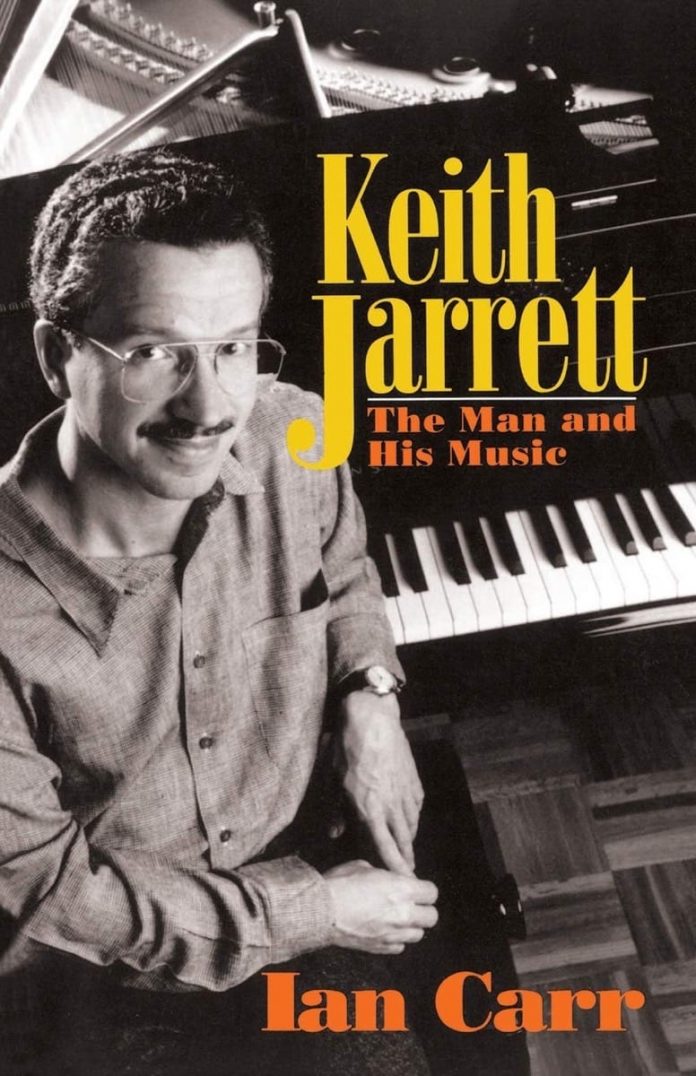

Keith Jarrett: The Man And His Music by Ian Carr. Grafton Books, 1991, hb, 223pp, 2 col, 20 b & w photos & discography, £17.99. ISBN 0-246-13434-8