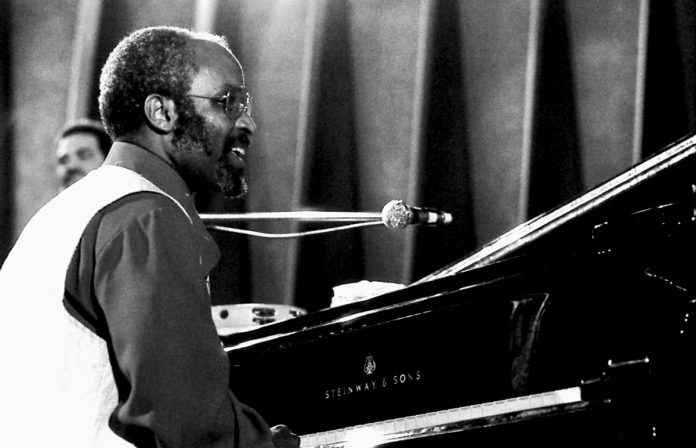

Pianist, composer and educator Junior Mance died in his New York City home on 18 January. He was 92, and had been in failing health for several years. His wife, Gloria Clayborne Mance, told friends “I know the world has lost a jazz legend, he was undoubtedly a very loving, happy and unforgettable person. I have lost my soul mate.”

In his long and distinguished career, Mance made over 50 albums as leader, and appeared as sideman with such major figures as the Adderley brothers, Gene Ammons, Dizzy Gillespie and Benny Carter. From 1954 he toured with Dinah Washington for two years, and in 1958 joined Dizzy Gillespie’s band. He also accompanied Joe Williams and Jimmy Rushing. In 1988 he was appointed to the faculty of the Jazz and Contemporary Music Programme at the New School University in New York City, and taught a young Brad Mehldau. Mance was inducted into The International Jazz Hall of Fame, in 1997 in Tampa, Florida.

Born Clifford Junior Mance, Jr. (“Junior” became his life-long nickname) in Evanston, Illinois in 1928, he was encouraged by his father to play boogie woogie and stride piano. (Years later, when Mance had evolved as a fleet-fingered bop-inflected pianist, his father chided him to “work on your left hand”). His mother had wanted her son to study medicine at Northwestern University in Evanston, but allowed him to enrol as a music major at Chicago’s Roosevelt College. When he discovered that the college did not offer tuition in jazz, he left, embraced and participated in Chicago’s flourishing musical night life, and listened to the recordings of Meade Lux Lewis, Albert Ammons and Pete Johnson. His later pianistic influences were Earl Hines, Art Tatum, Teddy Wilson, Bud Powell, Ahmad Jamal and Oscar Peterson.

In 1947 he made his first recordings with Gene Ammons’ band, and then spent two years with Lester Young, whom he greatly admired both as an individual and a person. “He wasn’t like a bandleader. He hung out with all of us. He was so down to earth. On the road he’d knock on our door every day to find out how we were.” Drafted into the US Army in 1951, Mance was befriended by “Cannonball” Adderley who helped him to get a placement in the 36th Army Band at Fort Knox, Kentucky. Discharged in 1953, he began a one year engagement at the Bee Hive Jazz Club in Chicago, playing with bassist Israel Crosby and drummer Buddy Smith. He also accompanied visiting musicians including Charlie Parker, Coleman Hawkins, “Lockjaw” Davis and Sonny Stitt. Norman Granz gave Mance his first recording session in 1959, which resulted in the Verve LP Junior with bassist Ray Brown and drummer Lex Humphries.

In the following decade, favouring the trio format, Mance recorded for the Capitol, Atlantic and Sackville labels, and in 2007, he and Gloria formed their own label, JunGlo. Their first release, Live At Café Loup, featured him with Hidé Tanaka on bass and Jackie Williams on drums. The group, with the addition of violinist Michi Fuji (another of Mance’s New School students) toured the US, Japan, Italy, and Israel in 2013. His last recording, For My Fans: It’s All About You, was released in 2015, after Gloria raised over $6,000 to finance the project. Outstanding among Mance’s prolific studio and live albums are The Soulful Piano Of Junior Mance (1960), Junior Mance Trio At The Village Vanguard (1961), Junior’s Blues (1962) and Blue Mance (1995).

The late Stanley Dance, who first heard Mance’s trio (with Keter Betts and Jackie Williams) play on one of the popular Floating Jazz Festival cruises in the 1990s, was surprisingly impressed. The trio “were playing with tremendous zest and authority, as if they had been together for years, not days. There were great rolling crescendos, exultant riffs hammered home with gospel-like enthusiasm, and long sighing diminuendos. Mance was clearly happy with his companions, and they with him”. Equally adept at boogie and blues, standards and stride, Mance infused them with a distinctive character and colouration. Baritone saxophonist Andrew Hadro who played with him offered this tribute: “As long as you were there to play, he was your friend. If you wanted to play some blues, you were cool. The only thing he liked almost as much as playing was hanging out, laughing and telling stories from his decades playing jazz everywhere and with everyone.”