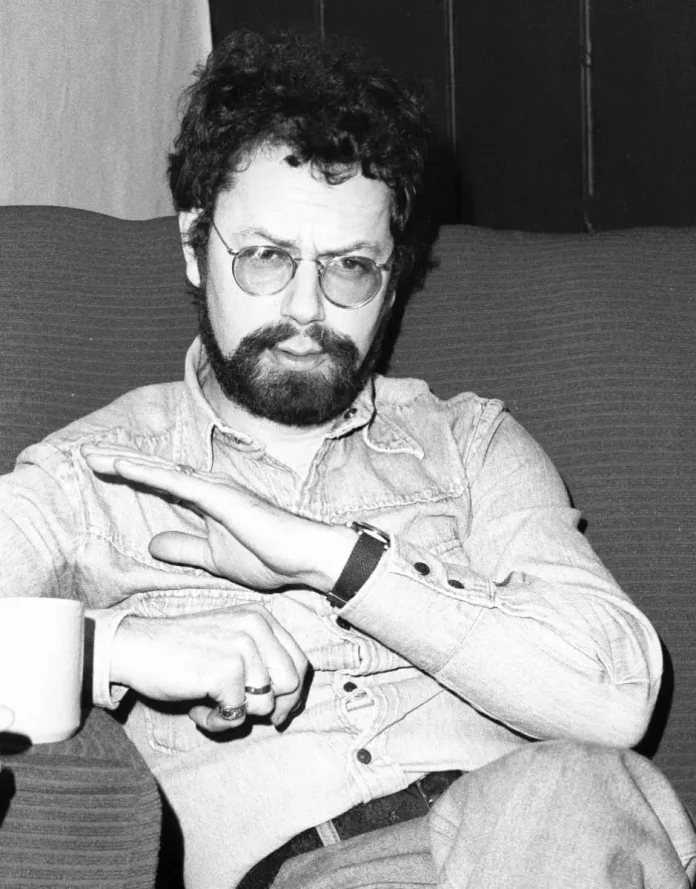

Ian Carr, jazz trumpeter and guiding light of Nucleus, is a highly individualistic musician, an articulate apostle of British jazz and a tireless advocate on behalf of those who believe that the home-grown product is as good as anything being played anywhere else in the world today.

Carr admits that as the leader of a particularly successful and remarkable bunch of musicians his opinions are not always impartial. But they are well reasoned, convincingly expressed and worth examining as pointers to a musical philosophy which is perhaps not as recognised in this country as it should be.

Like Quixote, Carr has a dozen mental windmills to tilt at – musical ignorance, the Musicians’ Union, pay for musicians, the scant regard for jazz exhibited by the national press, BBC et al – and he goes for each of them doggedly, snapping peevishly at their iniquities rather than blasting them with any stern conviction. Indeed, one suspects that his rage at these institutions is perhaps the slightest bit counterfeit, masking a slight affection for his targets although not detracting from his annoyance at their worst excesses.

Carr’s credentials are well-enough documented; from 1963 to 1969 he co-led a quintet with Don Rendell which for three years won first place in the Melody Maker jazz poll. Composer, musician and leader, Carr is a sometime journalist and a would-be author. He is writing a book about his life in jazz and about jazz as music. He is busy. He is successful and he is totally sceptical of any suggestion that his achievements are a matter for self congratulation.

A constantly recurring theme in his conversation is his disillusion with the interest in jazz in this country.

‘The way this affects me is that I get journalists come from all over the world and seek me out to do interviews and this applies to a lot of other British musicians as well. Whereas you rarely get interviewed at home.

‘Among the controllers of the media there is incredible ignorance; there is ignorance about rock music and pop music and also about jazz’

‘The fact remains that among the controllers of the media there is incredible ignorance; there is ignorance about rock music and pop music and also about jazz. Now rock and pop are fashionable so a producer can get away with murder and put something very rough on and because it’s in the fashion, it works. Whereas a producer who wants to put on jazz is really sticking his neck out.

‘Some jazz is of potential majority interest, some is minority and there is no distinction in the minds of the programme controllers between the two. To them it is all potential majority music and if it does not work on a majority level then that’s it – no jazz.’

Carr admits that Nucleus would never get a hearing on television’s ‘Old Grey Whistle Test’ which has become a rather precious showcase for art rock. But he would like to see the kind of format used by John Peel developed for television which might include jazz and classical music mixed together.

‘We want to break down barriers,’ he says. ‘We would like programmes that would have some rock, some classical and some jazz – the whole gamut of music on one programme.

‘We have nothing on television that is anything like that. Although I have done half an hour on Brussels television at peak viewing time of uninterrupted music with no announcements on at least two occasions in the last twelve months. Now in England I have never done more than 16 minutes on BBC2 at a non-peak time. It is absurd not to be able to do this kind of thing and in the long run the development of the music is going to be slowed up.

‘We realise that we will never appeal to teenyboppers. But there are more and more literate people and there is an audience for the kind of thing we are doing with Nucleus. It is quite a substantial one and with a little bit of preaching and a little more exposure, it could become very substantial indeed.’

Carr admits, with tongue in cheek, that he thinks all of his records are failures – ‘although magnificent ones’. He also admits that some of the material played by Nucleus has come off brilliantly and presumably accounts for the success of the group in Belgium, Germany and Japan.

Of his own roots Carr has little to say other than that he started playing traditional jazz, graduated to a Howard McGhee-ish sound and from there became his own man.

‘I admire guys like Miles Davis. He makes every note count and really tries to live it all the way. I admire people who really try to develop a built-in attitude that they ought to look for something fresh all the time.

‘Davis makes every note mean something although technically there are better trumpet players. But it’s a question of the craftsman and the artist. If you look at, say, Maynard Ferguson, he is twice or six times the craftsman and really only half or a quarter the artist. In a sense it does not matter how much technique you have got or how little if you are really saying something with your whole being.

‘I find a lot of interesting work being done by some English trumpet players: Kenny Wheeler, Harry Beckett and Henry Lowther and there are lots of younger guys like Marc Charig. I get something from all these people.

‘I am not so interested in the kind of music that is played by Chicago or Blood, Sweat & Tears. If I want to listen to really basic music that is vital as well, I would go to Howlin’ Wolf with his electric Chicago rhythm section. I also like Sly and the Family Stone because they have a fantastic feel. I also admire the Beatles and Mick Jagger who seems to be a very interesting guy.

‘I have also been to see The Who playing their album “Tommy” which I enjoyed although the volume was almost too much for me. But there is something in all these areas which is interesting and is happening.’

Would Carr consider working with The Who or a similar group? ‘I would certainly work with The Who if it was a mutual give and take operation. If it was just me having to go all the way with them I would not do it. I could certainly work again with the Animals, whom I knew very well, and with Alan Price who is an old friend of mine.’

Carr believes that a great deal of pop and rock music is becoming increasingly boring, limited, as it is, in its techniques. ‘A lot of it is extremely pretentious and the techniques are often pathetic.’

Although he sees no definite way ahead for Nucleus, Carr wants increasingly to draw upon modern classical composers. ‘I now want to listen to Bartok. I have only heard random pieces of his in the past, but I would now like to hear more.

‘I would like to possess more records by Gil Evans who has got that kind of influence and I really like Stravinsky. I have just read through the score of “The Rite of Spring” and in it I found that he uses a flatted tenth, a very bluesy chord in rock-blues music, which we use a lot.

‘What we do in Nucleus is simply to have one note which is a root and over that note we can play literally anything. That is the kind of freedom that we are interested in. Not total freedom where you don’t even have a root’

‘But I could never do totally without the ostinato bass rhythms. I always want, at some point, to have them in – the sheer rhythmic guts of the music. It requires incredible imagination to think up a really good, original, and vital riff which is only really a melodic and rhythmic fragment. But to get a good one is very hard without it sounding trite, corny or too pretentious.

‘Among my favourite things that big bands are doing now are, of course, Gil Evans, Monk, and Thad Jones and Mel Lewis. On Monk’s album “Four in One” the solo that he has transcribed for the line up is the most difficult thing I have ever heard from the point of view of just being able to play it physically. It is very exciting as music but not at all easy.

‘What we do in Nucleus is simply to have one note which is a root and over that note we can play literally anything. That is the kind of freedom that we are interested in. Not total freedom where you don’t even have a root, but we have one note and over it we have complete harmonic choice. We are interested in the building up of tension and in the releasing of it. In a lot of avant garde jazz I find tremendous tension but never a real release. So for me, totally free music has no drama. In about 1965-66 I spent a lot of time playing it and made an album doing it with John Stevens. When I finished with the old quintet, one of the things I decided was that never again would I play that kind of free jazz for a whole evening. As a part of something else it’s great – but it is only one part of the whole musical language. But I like to use the whole language which also includes rhythm, harmonies and everything else.

‘Of course, I like Ellington particularly and not only for his writing but for the feel of his music. His piano playing is fantastic from the rhythmic point of view and for its sound textures and pacing and spacing.’

The next major step for Carr is a specially commissioned work which will be played in the Queen Elizabeth Hall next year with a larger than usual line up very much like that used on his ‘Solar Plexus’ album.