I suppose that characteristics like the voluptuous and beautiful qualities of Stan Getz’s playing and the electrifying bustle of Coleman Hawkins shepherd the general listener easily into the beginnings of an appreciation of the great creative talents of such musicians. Having swallowed the bait, understanding of their inventive and other qualities follows automatically.

The mysterious vacuum that Miles seems to play in, the grand majesty of an Armstrong, the roaring intensity of Coltrane, and the poised warmth of Buck Clayton – all these are ear-grabbing elements which attract and captivate new listeners.

…it is doubtful if any of the avant-garde musicians of today would have the technical ability or musical perception to create anything on the lines of Lennie’s Crosscurrent

But one can be a great musician without possessing the out-going trademark which gains the voters. I suppose that in the dread pop field it would be known as a lack of show-biz appeal. People like Clare Fischer, Lennie Tristano, Lee Konitz and now our own Charlie Burchell (who is Charlie Burchell, you ask – stick around, kids) have all been prepared to opt out of public image-seeking and, although they’ve fought an uphill and often losing battle, seem to regard their music as such a precious thing that, rather than compromise it in any way, they’ve preferred to settle for the large and ungenerous cold shoulder offered by the great jazz public to anyone without a trademark or, in the case of some less-deserving successes, a gimmick.

Of course, chance is a fine thing. It probably favoured Monk who, on the face of it, would be far less acceptable to the g.j.p. than Bud Powell, a contemporary who trolled quietly into an unlauded end, while Monk, flying dizzily in the face of the logics of popularity, trundled to the heights of success and reaped all the financial rewards that the craftily directed Brubecks and Manns attained by stroking the pulse of the lower strata of the g.j.p. But the disasterous neglect of Powell, who was responsible for more influence on jazz over the last 25 years than any one man should be, is no concern of ours here. Bud is dead to everyone except posterity.

Warne Marsh is alive and, it is to be hoped, well somewhere in the United States. Marsh was first heard over here on some 78s recorded for Capitol under Lennie Tristano’s name. These few discs, which teamed the tenor player with Lee Konitz, showed Konitz, Tristano and Marsh to be way ahead of their time at the end of the 40s. True, Tristano’s group was moving in a direction which on the face of its appeared undigestible to the average jazz listener – even the musicians of the period, awed by the intensity and complexity of the Tristano team’s invention, acknowledged but were unable to be influenced by the new music. So, for once, a brilliant and inspired move forward in jazz was acknowledged but, because of its transcendental accomplishment, was feared and not incorporated into the mainstream of jazz.

Listening to those old 78s now, one realises that Tristano and his men introduced a whole new approach to jazz which is still, almost a quarter of a century later, too good for any of your run-of-the-mill jazz musicians to get with. Indeed it is doubtful if any of the avant-garde musicians of today would have the technical ability or musical perception to create anything on the lines of Lennie’s Crosscurrent. But the Tristanos spawned a whole off-cut of musicians (Charlie Burchell is one of the latest) who got the message and were content to sacrifice the kudos to retain the integrity of the form and their invaluable membership of what must be the most exclusive and one of the most artistically rewarding clubs in the whole of jazz.

Despite Ornette’s trumpet playing and all the self-sycophantic rubbishings of the free-formers, technique combined with invention and emotion still survive in jazz without the mandatory imposition of showmanship. For, throughout all these years since Crosscurrent, the Tristano school has continued underground, working for, to paraphrase the guv’nor, Lennie’s pennies, but showing a determination for survival which would break the heart of a Canadian seal-clubber.

Warne Marsh is the prototype, the inspiration and the martyr. He’s like Joan Of Arc without the Palladium trappings. Completely devoid of showmanship, trademarks or gimmicks, he is probably one of the greatest tenorists of the last quarter-century

Warne Marsh is the prototype, the inspiration and the martyr. He’s like Joan Of Arc without the Palladium trappings. Completely devoid of showmanship, trademarks or gimmicks, he is probably one of the greatest tenorists of the last quarter-century, and ranks with Hawkins, Lester Young, Getz, Rollins and Coltrane – arguably none of them are his peer, in the same way that one cannot value any one of them against the other.

Marsh, like his contemporaries, refuses to go out and look for a public – if they want him, they must come and find him. It’s been this way for twenty years, and yet his music, heard today, is as advanced and as rewarding as anything our new young bloods are putting out, and a darned sight more mature and accomplished.

Fortunately he has a friend in the British bassist Peter Ind, himself an offshoot of the Tristano cartel, who combines a similarly frightening ability on his instrument with such an intense love for his music that I hope I never meet him – I’ve been like this for so long that I don’t want to be changed.

Peter’s devotion to this particular corner of jazz – and ‘corner’ seems a minor word for such a field, has pushed him into risking what on the face of it is not a glowing commercial venture. This is the induction of the Wave record label, which features in the main jazz that Peter was able to record during his stay in New York over the last decade. Mark Gardner reviewed the initial issue of seven LPs in our March issue. I would like to endorse and expand his enthusiasm for all the issues, but with particular emphasis on three of them (obviously not many of our readers are going to be able to afford the whole lot, although anyone that can is well advised to).

The Warne Marsh (Wave LP 6) is wonderful, but it is run very close by Sal Mosca and Peter Ind (Wave LP 2), which at last gives a decent exposure to one of the great pianists of the post-bop era (a pity that someone can’t do the same for Johnny Acea and Joe Albany).

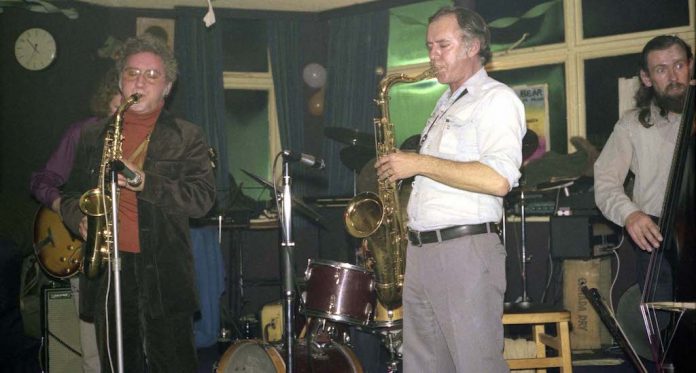

Trying to avoid a strain on your resources, let me select particularly the album from the 1969 Richmond (Yorkshire) Jazz Festival (Wave LP 5) which includes Ind and Bernie Cash on bass, Derek Philips (beautifully complementary to the other musicians and a most original voice on guitar) and the aforementioned Charlie Burchell on tenor. Burchell is a Marsh disciple (it must have rubbed off via Ind?), and the abilities he displays here come as a huge refreshment from the ‘traditional’ modern tenors on the one hand, and the beserk ones on the other. Of the new names, only Jim Philip has impressed me so much, and Burchell, like Coe, Morrissey, Scott and Hayes, continues a line of Englishmen who have challenged strongly in world terms on this instrument.