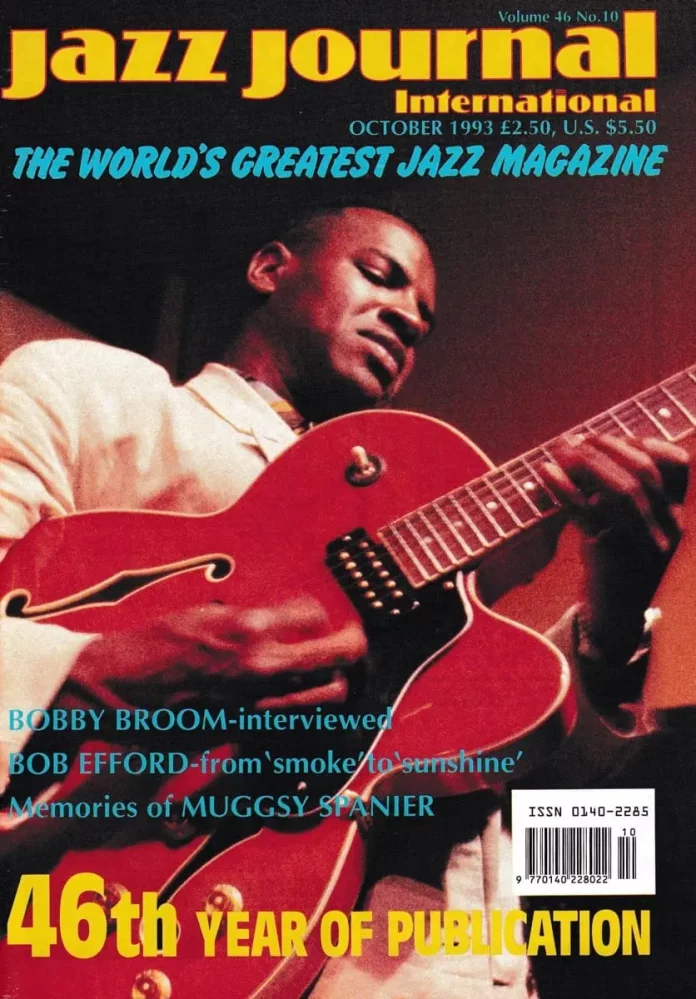

To the casual observer, Bobby Broom might easily be mistaken for one of his first inspirations, George Benson. Sporting a similarly mellow-toned deep-bodied jazz guitar, he has toured and recorded with such soul-funk luminaries as Dave Grusin, Tom Browne and Rodney Franklin, and in 1981 he led his own date for Grusin’s MoR label GRP. However, he neither sings nor scats, and nor does he share Benson’s latterday preoccupation with moonlit romance. Instead, a few distractions apart, he has concentrated on playing guitar and building on the legacy of Wes Montgomery and Grant Green. Cubism, a recent issue by Ronnie Cuber on Fresh Sound (FSR-CD188) bears ample testimony to his achievements in the straightahead mode. Added to a vigorous blues and bop style are the harmonically abstract Coltrane and Tyner touches which Montgomery, Green and Benson seem largely to have missed. The combination of this colourful modern syntax with the traditional virtues of a hot, percussive attack, a strong melodic sense and warm, imaginative comping has enabled Broom to develop a new perspective on a style that might have been thought unimprovable.

Broom’s appearance in London in May as part of Courtney Pine’s American Band was another in a long line of star assignments that have included Art Blakey, Kenny Burrell, Stanley Turrentine, Max Roach and Miles Davis. In fact, Broom started at the top, playing Carnegie Hall with Sonny Rollins at the age of 16.

‘I was doing an off-off-Broadway play, Young Gifted And Broke, both acting and playing, when Sonny Rollins’s guitarist happened to be in the audience and asked me to audition. Sonny asked me to go on the road, but I couldn’t go, so he called me to do this concert at Carnegie Hall with Donald Byrd.’

Rollins wasn’t quite Broom’s first gig, but he did his dues-paying in some distinguished company. Like most players, he got his start sitting in with local groups, and ‘local’ being New York, the groups happened to be led by Al Haig and Walter Bishop Jnr.

‘Al Haig had a steady gig three or four nights a week at a place on the East Side. I sat in one night and he just asked me to keep coming around.’ Broom knew this was a great opportunity to learn and be seen, but like any learning process it seemed to involve a measure of bluff: ‘He’d say: “You know this tune?”, and I’d say “I mighta heard it before,” and he’d say “Well, just pick up on the second chorus”. So that’s how I learned a lot.’

Despite meeting the rigorous demands of gigs with Haig, Bishop and Rollins, Broom, born in New York on January 18, 1961, had not been a cradle bebopper. He’s a good example of the idea that a taste for crossover can lead to the ‘real thing.’

‘I started playing, I guess, when I was about 13 or 14, but I never really cared much about jazz. I had a teacher that was a jazz player and he used to tell me who to listen to. I’d blow him off, until I heard somebody like Grover Washington or something, and that attracted me to the word if nothing else. Then I heard George Benson and started to realise there was a lineage and history and just tried to listen to as many records as I could. I went to the High School of Music and Art, which didn’t have a specified program for guitar, since guitar is not an orchestral instrument. So they had me play upright bass for the first year, until I got into the jazz band.”

Although the seventies were hardly fat years for jazz, Broom found in the work of soul-jazz artists like Washington and Benson a route to the blues and hard bop. He had little time for the rock-oriented fusion that held sway during his teens.

‘I was into Herbie, but I didn’t really like fusion just because it moved around so much. I could never get into the groove long enough before they were going on to something else. I was just attracted to the particular style of guitar playing which was George Benson and Wes and Grant Green, rather than Al DiMeola’

‘I had a lot of friends that were into fusion – Chick Corea and Return to Forever were big, and Mahavishnu and Herbie and The Headhunters. I was into Herbie, but I didn’t really like fusion just because it moved around so much. I could never get into the groove long enough before they were going on to something else. I was just attracted to the particular style of guitar playing which was George Benson and Wes and Grant Green, rather than Al DiMeola and people of that more rock-influenced style. That’s just the way I leaned, and I went back from Wes to hearing about Charlie Parker and Sonny Rollins and early Coltrane.’

Broom’s own investigations of jazz were reinforced by various spells in formal education. After the High School of Music and Art, he followed the time-honoured route to Berklee School in Boston, but only stayed a year. He enjoyed the company of players who would later make their mark, such as Victor Bailey. Branford Marsalis, Marvin ‘Smitty’ Smith and Terence Blanchard, but since all attention seemed focused on New York, he decided he would go home and meet the rest when they got there.

While at Berklee he had played in a recital for pianist James Williams, and the association was to prove a good investment. Back in New York, Broom found that Williams was playing with Art Blakey.

‘He told me go and get your guitar, so I started sitting in with Blakey, and this was around the time that Wynton was coming around and sitting in too. Wynton had an Afro out here and everybody was wearing overalls. Blakey wore overalls and a work shirt. Then the next thing you know, everyone had on ties and suits.’

At the same time, the other side of Broom’s dual musical personality had led to gigs with Tom Browne, the jazz-funk trumpeter, and Broom found himself in a dilemma.

‘Blakey asked me to join the band and told me I was an official Messenger now. So that was cool, but Tom Browne was getting ready to go on the road, and had done his record, so I chose to go with Tom. A lot of the jazz guys got on my case. I think they liked the way I played and didn’t understand why I would go with Tom Browne rather than Blakey.’

Surprisingly, given Browne’s high commercial profile, money was not at the root of Broom’s decision.

‘I have to say it was kind of a personal thing. I had heard that there was some kind of drug involvement in that band, and I was deathly afraid of drugs. So I went with Tom and started recording with him, and we did Funkin’ For Jamaica, which was big, and from being associated with Tom I was signed by GRP and in 1981 I released a record called Clean Sweep. I didn’t really follow it up, I didn’t tour with it, but it kinda got my foot in the door.’

‘There was always buzzing around about the Miles gig, and I think maybe his road manager one night in a drunken stupor told me: “Yeah, you know, after Stern, you’re gonna get the Miles gig.” This is like 1982, and five years later Darryl tells me to send a tape’

Another call from Sonny Rollins took Broom back into the hard bop arena for three or four years from 1982, but at the same time he was involved with Japanese funk saxophonist Sadao Watanabe, Rodney Franklin, and ‘all that GRP stuff’. A period of disillusionment was followed by a move to Chicago in 1984 and a resumption of his studies, this time at Columbia College, where he completed a BA in Music. Later came teaching posts at the American Conservatory of Music, now Roosevelt University. However, Broom had by no means retired from public performance, and from 1985 he played and recorded with Kenny Burrell’s jazz guitar band. Before long he was busy enough to face difficult decisions again. It began when his friend, the bassist Darryl Jones, told him: ‘Miles wants you to send him a tape.’

‘I had been hearing about playing with Miles ever since living in New York. I used to hang around 55 Grand St all the time, with Mike and Leni Stern and all that. There was always buzzing around about the Miles gig, and I think maybe his road manager one night in a drunken stupor told me: “Yeah, you know, after Stern, you’re gonna get the Miles gig.” This is like 1982, and five years later Darryl tells me to send a tape. So I made this tape of me playing my version of rock guitar – what I thought Miles wanted to hear, and it sounded good, but it wasn’t truly me. So he heard the tape and said “Yeah, come on to New York.”

‘It was a weird situation though, because right then the first Kenny Burrell record came out and we had our first gig with him. I told Kenny I wanted to do this Miles gig, and he gave me a real hard time. So I called Miles and told him I gotta do this gig with Kenny Burrell, and he was cool.

‘I did five gigs with Miles. He was looking for guitar players and he couldn’t find one. He went through a bunch at that time – Robben Ford, Hiram Bullock, and then me. And then he got Foley after that. To have had that experience was cool, the money would’ve been great too, but you can’t have everything. And I kind of felt I was getting bored after the fourth gig. I just don’t think it was particularly my bag, or a situation I was comfortable with.’

Despite Broom’s reservations about playing with Miles, there are elements in his playing – chromaticism, chord substitution, outside playing – which recall earlier Miles sidemen, and one in particular.

‘Well, truth be told, I listened a lot to Scofield, although I don’t think I ever tried to transcribe a whole lot of that stuff. I was the same way with George Benson when I was a kid: “Look, I’m not gonna be able to play this shit so I’m not gonna even worry about it. I’m just gonna listen to it and if I can pick up a few things here and there I’ll learn ’em.”

‘I have worked on extending my ear, and people tell me that all the time, about being outside, and I laugh because for such a long time I didn’t know where to begin to take my playing in that direction. I laugh because I used to wanna know what they meant when they said play outside. I’d play something up a half step but that didn’t cut it for me. So I just practised and studied and just tried to come up with a concept for extending the chords.

Of Slonimsky: ‘I got that as a high school graduation present and I couldn’t find anything that I could relate to any chord until I got to the section on bitonal arpeggios, and it made sense. So it’s just that one little thing I’ve been milking to the hilt’

‘I think a lot of it is just relative harmonies. Musicians all know that if you got a major chord you can play in its relative minor, so I just try to extend that, maybe going to the dominant seventh in the key of the minor chord, then to its minor seven flat five, and vice versa when the chord’s a minor. And then there’s some stuff from the Slonimsky book I apply that to. I got that as a high school graduation present and I couldn’t find anything that I could relate to any chord until I got to the section on bitonal arpeggios, and it made sense. So it’s just that one little thing I’ve been milking to the hilt.’

Just as Broom’s playing mixes the old and new, so his sound is a combination of the classic jazz guitar tone and contemporary electronic technology. An endorser of Yamaha guitars, he plays both their full-bodied model and a 335 style guitar. Talking with George Benson has made him even more aware of the subtleties of tone inherent in the hollow-bodied guitar.

‘George has a closet full of L5s, and he was telling me you need to play an L5 because of the way the wood resonates, and it’s true. You get those older guitars with that rich wood, even unplugged you can hit a string and it rings. You don’t hear any metallic thing from any part of the guitar. It’s all wood and nice, warm sounds. I’m just becoming aware of that kind of stuff. So one day, when I have nothing better to do, I’ll start collecting.’

The other element in Broom’s sound, one which helps give it an edge and presence, is his amp set-up.

‘The set-up I had on that Cuber record was really nice, and I was starting to get a lot of compliments. It took me years and years to get that sound. I was using this Carver power amp, a Peavey programmable preamp, a Quadraverb and a couple of Gallien-Kruger speakers. I tried different things and just really liked the warmth of that.’

Selected discography

Sonny Rollins: No Problem and Reel Life (Milestone)

Dizzy Gillespie: Endlessly (Impulse)

Kenny Burrell: Generation and Pieces Of Blue & The Blues (Blue Note)

Ronnie Cuber: Cubism (Fresh Sound)

Bobby Broom: Clean Sweep (GRP)