In the introduction to Ms Golia’s book Coleman is quoted as saying: “The theme you play at the start of a number is the territory. And that which comes after, which may have very little to do with it, is the adventure.” It explains Coleman’s style of music and philosophy concisely but probably meant little to those people who found it difficult to accept.

The first part of the book deals comprehensively with living conditions and the extreme poverty of the part of Texas where Ornette grew up and played his first R&B gigs. It will be of interest to people interested in the 1930s social scene but most likely less so to jazz enthusiasts.

Part two covers Coleman’s music-driven trajectory, as the author puts it, from Texas to New Orleans, to Los Angeles and New York. In Los Angeles he met Sonny Rollins for the first time and the two of them headed for the coast and blew saxophone music out to sea. He found a home in New York and from there commuted regularly to Europe taking his brand of free jazz with him and distributing it. Part three deals with Ornette’s homecoming to Texas and the inauguration of The Caravan of Dreams, the theatre, concert hall and performance centre which he opened with a week’s engagement for his group.

There is coverage of Ornette’s initial breakthrough in 1958 and the recordings of his classic quartet in 1959. The long engagement at the Five Spot Café in NYC is put into perspective: although the run was phenomenally successful in terms of numbers attending, many musicians, not to mention the public, found Coleman’s music incomprehensible. Perhaps saxophonist Jackie McLean’s verdict, quoted in this book, sums it up best: “You spend your life making a three-piece suit that’s incredible and this guy comes along with a jumpsuit and people find it easier to step into a jumpsuit than to put on three pieces.” No doubt McLean’s comments referred mainly to musicians who found it easier to play “free” than do the difficult stuff played by Parker, Coltrane, Rollins and company but a lot of jazz fans seemed to jump on the bandwagon just because it was the latest thing.

Ornette’s early struggles for recognition are covered and there is much about his 70s and 80s activities, including his trips to Morocco where he met and recorded with the musicians of Joujouka. He played in Africa with local musicians and found the experience liberating. Around this time, he also met and became friendly with novelist William S Burroughs, who was to fiction what Ornette was to jazz. There was a new, freer approach in both cases where the rules were jettisoned.

Although the book covers Coleman’s life in great detail I wonder if a little more attention could have been given to his early, phenomenal success in 1959-1961 and the great contribution of the sidemen that supported him. It is sometimes overlooked how important the work of those musicians was in adapting to Ornette’s music and finding ways to accompany him. It was Ornette’s vision and his alone but without the contributions of Charlie Haden, Billy Higgins, Eddie Blackwell, Jimmy Garrison and Scott La Faro, where would he have been? Can anyone imagine Ornette playing in 1959 with a standard swing or even bop rhythm section behind him? Don Cherry too was crucial to Coleman’s early success. He and Coleman seemed to magically breathe together on those brief ensembles.

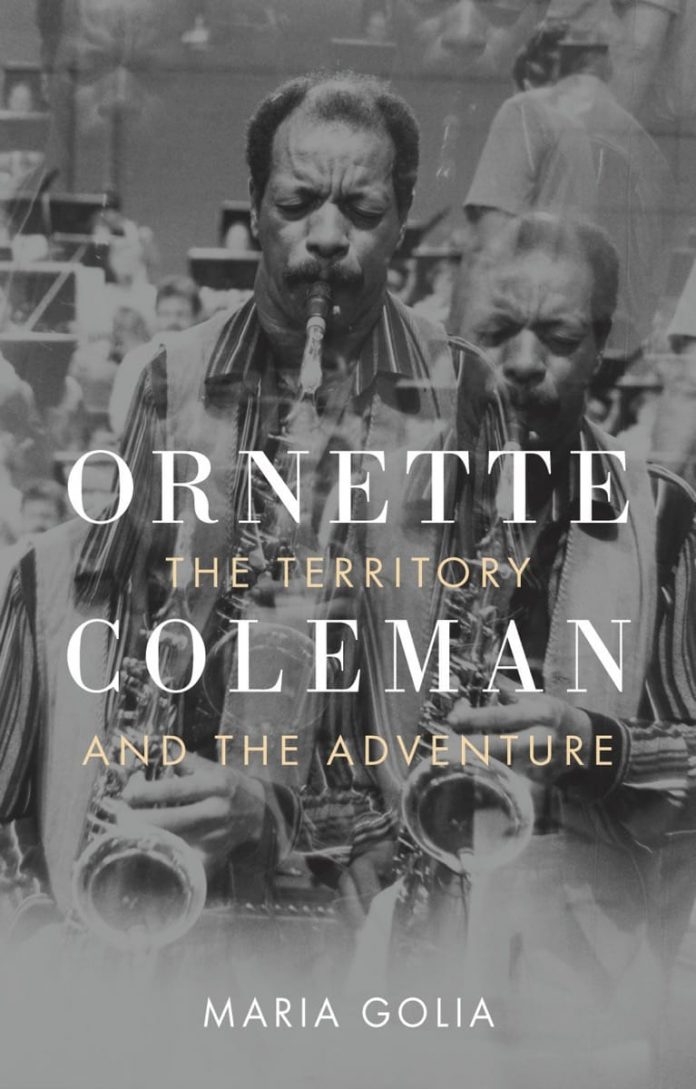

Ornette Coleman: The Territory And The Adventure by Maria Golia. Reakion Books Ltd, hb, 368pp, £16. ISBN 978-1-78914-223-5