It’s not easy to be a successful ex-prodigy. In wider musics than jazz, many a boy (or girl; pace, Greer) wonder has spent near-lifetimes living up to – or living down – the curse of an over-auspicious debut. No room for gradual, graceful maturation here; whosoever outstrips ordinary mortals at age 10 often keeps being expected to do so, in the face of ever-stiffer competition from the non-prodigies, at age 20, 40 or longer.

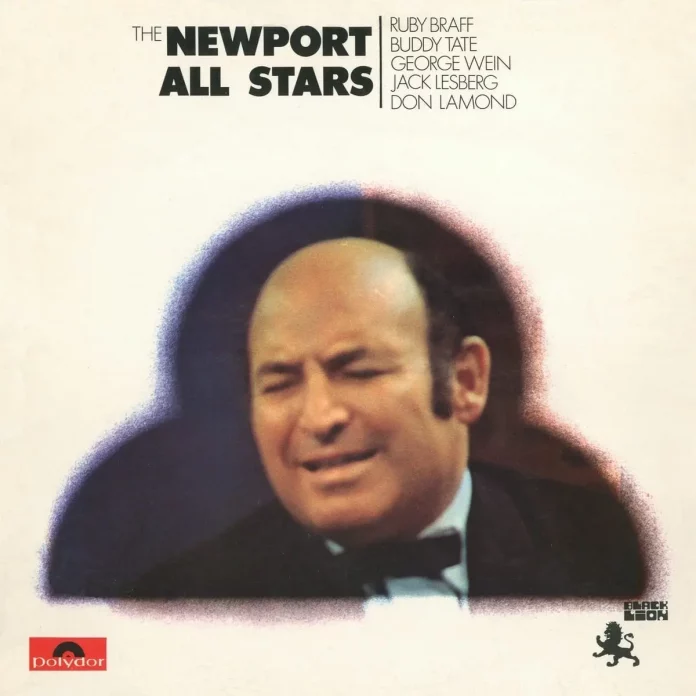

Ruby Braff was no kid when those now-legendary Vic Dickenson Vanguards appeared in the shops; he’d been around Boston quite awhile, ripening in company with Vic, Pee Wee and other dignitaries up from local 802. But with Jeepers Creepers, Russian Lullaby and the rest, he arrived: a new, authoritative voice, a musical individualist to be heard and pondered.

Now, 20 years on, the prodigy is long since an adult; on the basis of this 1967 recording and several others, plus occasional appearances in this country, there has not been a lot of development. Even in the best of Braff’s performances here, a thoughtful Body And Soul, there is a disturbing complacency, a static quality often found in the playing of Bud Freeman and other men far older than Ruby. The figures, the approach, are still boy-wonder Braff; but now the man is a hardened professional, and appears to have taken on little added depth with the years. On the contrary, he has become almost predictable.

This need not be so. The recent appearances of Billy Butterfield in this country were an enlightenment in this respect. Butterfield, at 53, gets better and better, his jazz more and more intriguing – all with a tone capable of coating even grotty old Hammersmith Odeon in purest sterling silver.

Braff apart, the record does well by Tate, whose breathy balladeering on Surrender is in the noblest of tenor traditions and who elsewhere shows himself a highly skilled, if not startingly individual, soloist.

George Wein has always been the man with the gigs, perhaps explaining why his competent but consistently uninteresting piano has appeared in the company of some of jazz’s greatest older generation names. To allot him a four-minute feature on Please Don’t was simply an indulgence. Drummer Lamond plays stiff, unresponsive time which more frequently holds up the action than promotes it.

In sum, 40 minutes of disappointing music.

Discography

Take The A Train; These Foolish Things; My Monday Date; Body And Soul (20 min)—Mean To Me; I Surrender Dear; Please Don’t Talk About Me When I’m Gone; Pan Am Blues (20½ min)

Ruby Braff (cnt): Buddy Tate (ts); George Wein (pno); Jack Lesberg (bs): Don Lamond (dm). London, 28/10/67.

(Polydor Select 2460 138 £1.95)