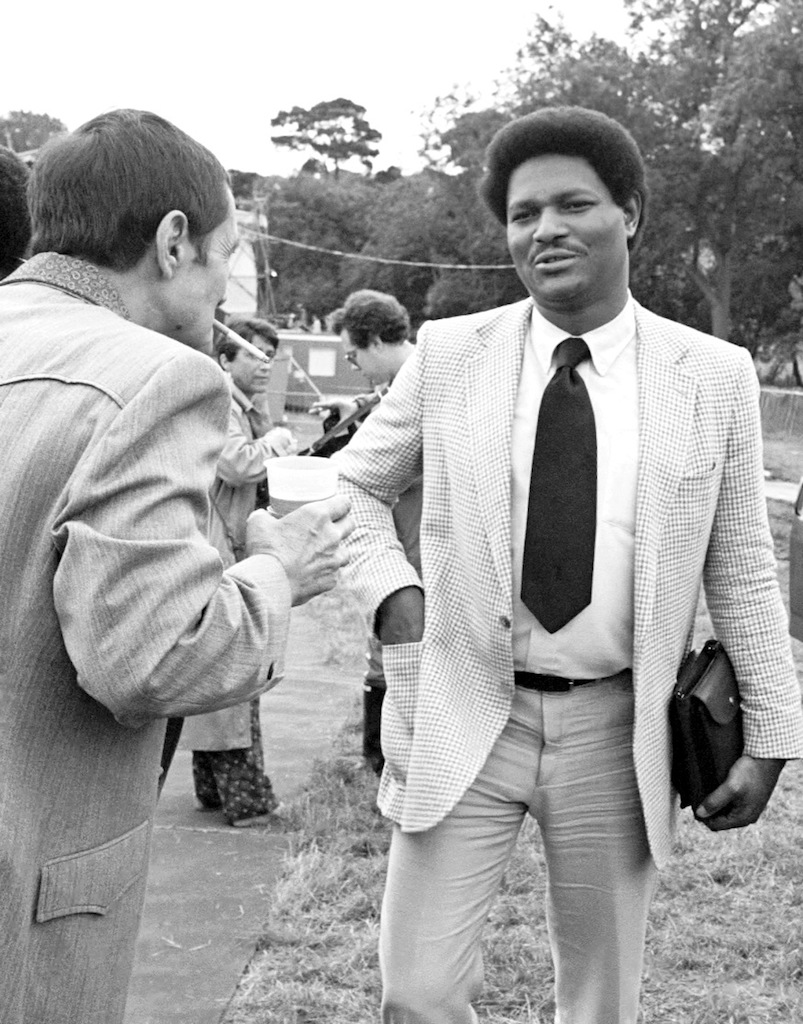

I’ll never forget the early occasions when I saw McCoy Tyner in concert. The first time was at Ronnie Scott’s in London, where I sat virtually at the end of the piano, opposite to McCoy at the keyboard end. As a young music student I’d never before heard a sound like that from a piano, and even now some 35 or so years later, I’m not sure I’ll ever hear the like of it again. The second occasion was at a Summer Jazz concert at the Corn Exchange in Cambridge, in the late 1980s/early 90s, and when Tyner’s trio came on to follow the excellent young British support band, it sounded in some ways rather like a masterclass from the more experienced American musicians – Tyner’s band quickly lit up the room with its insistent, rolling grooves, easy swing, wild solos, and even catchy tunes.

McCoy Tyner, a giant of jazz piano, and, I would argue, of 20th century piano as a whole, died 6 March 2020, but unlike some other recent jazz casualties, it seems that it was not from the coronavirus. He is survived by his wife Aisha, his son Nurudeen, three grandchildren and siblings Jarvis and Gwendolyn-Yvette.

He was born 11 December 1938, and, like his neighbours, the piano-playing brothers Bud and Richie Powell, hailed from Philadelphia. Tyner long outlasted Bud and Richie in terms of lifespan, but something of them seems to have continued in his music. Tyner was always a fan of Bud and Richie, at times utilising Bud’s bebop “shell” chords, typically of root and 7th and root and 3rd (mostly when he played standard tunes rather than his own compositions), and also being influenced by the percussive and sometimes dramatic nature of Bud’s playing. It would also seem possible that he initially got the idea for constructing chords in 4ths from Richie, who liked to play suspended chords. Here, unlike conventional major and minor chords, the 3rd was replaced by the 4th and gave the effect of the chord just hanging there, neither major nor minor, suspended in harmonic air. This was unusual in jazz in the very late 1940s and early to mid 1950s. However, said Tyner, “I never copied what he did, but I certainly appreciated it”.

‘I was drawn to different types of composers. For instance, I liked Debussy, and I liked Stravinsky’s music and a lot of Ravel … I just liked hearing different intervals and different voicings’

I recall the late author, teacher and pianist Lionel Grigson (himself quite a fan of Tyner) telling me in the mid 80s that he thought Tyner was over-recorded. Well yes, even by then he had quite a discography under his belt, but I’m not so sure that he was so much over-recorded as under-documented in the written word. There are some notable exceptions among writers, including Ben Sidran, Len Lyons, Sami Linna, Stanley Dance, Ethan Iverson, Alyn Shipton, and Ted Panken, who were genuinely interested in Tyner, but it does seem that he was often under-appreciated, and in some cases completely misunderstood. Tyner’s style isn’t entirely about that thundering left-hand and fast pentatonic scale phrases in the right-hand. Yes, that might be our first thought about him, but in contexts where he played standard tunes in his own groups and for band leaders other than Coltrane, he had a whole array of other skills to offer, with subtle and complex reharmonisations and a light overall touch, both when he was younger and sounding rather like Herbie Hancock (or was it the other way around?) and when he was older and at times sounding a little like Oscar Peterson.

The harmonic and improvisatory innovations that have led to our general impression of what McCoy sounds like should be seen not as revolutionary, but rather as adding to his clearly extensive understanding of the evolution of jazz piano. He demonstrated this in his playing. His influences were broad enough to range from the much earlier work of Earl Hines, Art Tatum and Duke Ellington to Bud and Richie Powell, Thelonious Monk, Red Garland and Horace Silver.

In an interview with Tyner for Keyboard magazine, interviewer Bob Doerschuk said “Many pianists, in imitating your style, seem content to just pile fourths on top of one another”. Tyner answered: “Well, there are other things involved. It’s not just a pile of fourths. I play a lot of fifths in my left hand, you know, and they do the same thing as fourths: They open up the sound. I don’t close my sound in, and that allows me to play other things superimposed on the chord, since there is a lot of space between the intervals. But there are thirds, seconds, octaves and clusters there too. When I put clusters together, there may be fourths in there, but there are also seconds, thirds – it’s a mish-mash of a lot of different things”.

Ben Sidran, in a 1985 interview with Tyner, refers to the pianist’s style at the age of 19: “…even then, you had an identifiable style that didn’t sound like all the other piano players at that time. You had tremendous technical facility, obviously, but there was something about the intervals you played, I suppose, that just jumped out. How did you develop that intervallic sense at such an early age? What did you do? Tyner replies “I was hearing different harmonically, when I was very young … I was drawn to different types of composers. For instance, I liked Debussy, and I liked Stravinsky’s music and a lot of Ravel… I just liked hearing different intervals and different voicings”.

As well as the classical tinge, there was also a strong Latin tinge in Tyner’s playing, and he in turn influenced pianist Michel Camilo amongst many others. It can also be easy to forget the quality of Tyner’s compositions – e.g. Passion Dance, Search For Peace (both from his Blue Note debut album), and Walk Spirit, Talk Spirit which I’ll come back to below.

Sami Linna, in a very recent doctoral dissertation entitled McCoy Tyner, Modal Jazz, and the Dominant Chord, has an alternative view of what it is that McCoy actually did with his note and chord choices

Sami Linna, in a very recent doctoral dissertation entitled McCoy Tyner, Modal Jazz, and the Dominant Chord, has an alternative view of what it is that McCoy actually did with his note and chord choices, compared to the generally accepted understanding that McCoy was using quartal harmony, modes, pentatonic scales and “out” playing or side-slipping. Linna says “Tyner doesn’t seem to come up with melodic material by actually utilizing modal scales and scale sequences. Instead, he achieves modal sounds by making use of dominant chords and II-V progressions from other keys”. I only have a fairly limited word count here, as opposed to 80,000-100,000 words, so there’s no real space to discuss this any further for now, but after having just a brief look at what the dissertation has to offer, it seems well worth a thorough read. However, it’s also worth noting that the generally accepted theory of what McCoy did has enabled many pianists to imitate him, whether closely or just as a hint, so perhaps it wasn’t too far from being correct.

Unlike a number of his contemporaries in the late 60s and early 70s, Tyner never diverted from the piano to use electro-mechanical pianos and synthesisers, either instead of or as well as the acoustic piano, a factor which may have contributed to him getting little work at the time. He did however sometimes play harpsichord and celeste (both acoustic instruments) on his album Trident, which may well seem less surprising once you’ve read what’s below.

Most research and pedagogy in jazz (because it’s a music that originated largely from an aural tradition that then developed to include more notated sources) has concerned itself with working out what notes have been played, why they’ve been played, and labelling the way in which they’ve been used. However, in the case of McCoy, amongst others, we should have a closer look at the musician’s performance techniques, particularly in terms of articulation – I think that a considerable part of why McCoy sounds so individual and distinctive is because of the completely contrasting playing techniques he uses in the left and right hand. What he does with them simultaneously is quite a feat in terms of technique.

The left hand typically plants low fifths and octaves with a hard attack, and initially with the sustain pedal depressed, and then it jumps immediately up into the middle range to place open-sounding chords in fourths, sometimes played with tremolando – overall, something like a cross between the left-hand function in stride piano and the left-hand of some of Chopin’s Nocturnes, albeit with a much heavier touch

As an example, take a live group performance by McCoy from the 1970s of his own tune, the aforementioned Walk Spirit, Talk Spirit (which sounds like it could have been a jazz anthem for the late 1960s), and watch what he actually does with his hands when he solos (see YouTube link below, starting around 6:50). The left hand typically plants low fifths and octaves with a hard attack, and initially with the sustain pedal depressed, and then it jumps immediately up into the middle range to place open-sounding chords in fourths, sometimes played with tremolando – overall, something like a cross between the left-hand function in stride piano and the left-hand of some of Chopin’s Nocturnes, albeit with a much heavier touch. Also note his quite low seating position on the piano bench, which typically is the height at which most players would seek to sit if wanting to play without too much attack, and also achieve a nice tone for lyrical passages, which debunks some opinions about Tyner being heavy-handed – Glenn Gould and Bill Evans sat in a similarly low position at the piano.

However, in complete contrast, the right hand often plays staccato rather than legato, particularly when utilising pentatonic scales, and avoids using the thumb (with it dropped back and hanging down, away from the surface of the keys). The resulting effect, coupled with Tyner’s oft-discussed note and chord choices, sounds quite unlike anything else in piano music, ever. The reason why the right hand plays staccato is because of the finger patterns that can and can’t be used when not using the thumb. Smooth movement through a string of notes to make a phrase on the piano keyboard, conventionally requires the thumb to move under other fingers at times, in order to extend the range of notes that can be played. However, the right-hand technique that Tyner utilises here is similar to that used in early harpsichord playing, so that’s why it’s perhaps no surprise that Tyner plays harpsichord on the aforementioned album Trident.

Anyway, I’ll leave you with contemporary pianist Ethan Iverson’s words, briefly summing up McCoy’s huge contribution to jazz, and his lasting effect on generations of jazz pianists: “McCoy’s influences are discernible, but in the end he sounded absolutely like no one else. As the Coltrane group grew more popular, Tyner’s approach travelled like a shockwave through the community. No one – not Art Tatum, not Powell, not Monk, not Bill Evans – dropped a bomb on jazz pianists quite like McCoy Tyner. There was pre-McCoy and post-McCoy, and that was all she wrote”.