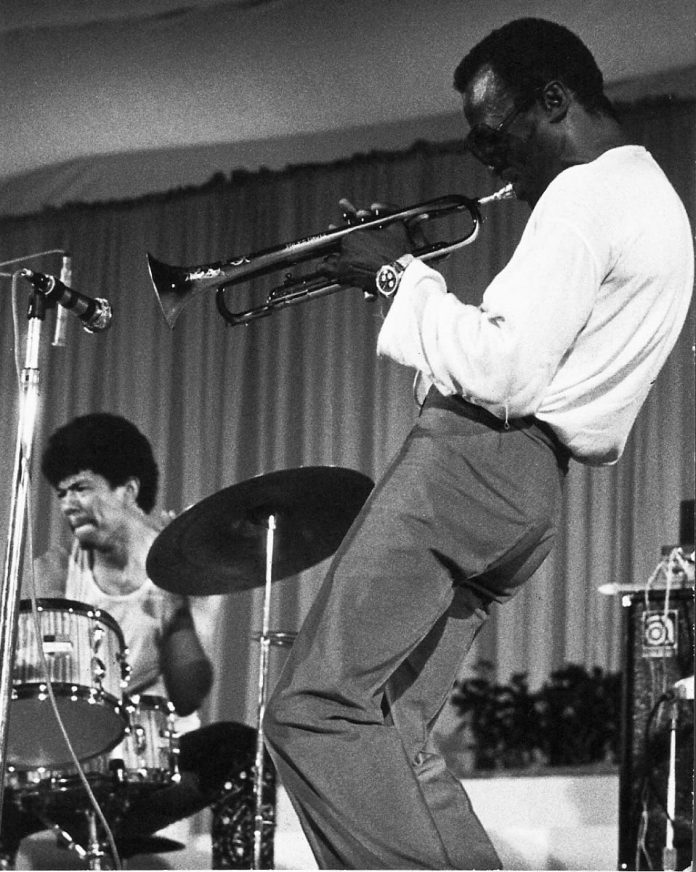

A packed and highly enthusiastic house greeted Jack DeJohnette for a drum clinic at Ronnie Scott’s late last year. It was part of a series of European clinics given by a drummer with the most diverse experience of jazz and rock drum styles, and a name featured high in numerous polls.

DeJohnette didn’t follow the kind of demonstrative style one might expect of a clinic. Rather than play phrases and analyse them, he offered a comprehensive workout that lasted about 75 minutes non-stop, exploring every aspect of pace, volume, rhythm and orchestration. It became a one-man free jazz concert, and at the same time a demonstration of an invincible technique that elicited huge applause. Without a frame of reference in the form of rhythm and melody from other instruments, my interest wandered, but the purpose of the clinic – a study of technique – was amply served by this marathon performance.

Then came the question and answer session. PR men waited in trepidation – what would follow – an embarrassing silence or a successful presentation for Sonor drums? The earlier exuberance of the audience didn’t betray its promise, and DeJohnette spoke in a soft drawl for about half an hour about his technique and art.

DeJohnette has played drums for about 18 years, although his first instrument was the piano. He fell into playing drums by accident at high school: “I couldn’t play piano in a marching band so I had to switch to something else.” The same was true of the concert band, where DeJohnette first played double bass then percussion in the absence of a piano.

‘There are a few other drummers around who try and make the drums sound more melodic too – Max Roach is one of them, and one of my favourite drummers. He’s also a good composer, and one of the first guys to tune drums in the forties and fifties’

“My first inspiration came from an album called ‘But Not For Me’ with the fantastic legendary pianist Ahmed Jama! and a drummer called Vernel Fournier who played brushes, so I ran out and bought some. “Then a friend left his kit in my basement, so I took my records downstairs, played along with them, and learnt the rudiments from a book. After that I started going to Chicago jam sessions, getting introduced to musicians who’d take me under their wings and give me instruction and guidance. I’ve been playing drums ever since and the more I play them, the more I really dig them, so I hope to continue searching and exploring and trying to create fresh ideas in music for everybody to listen to and enjoy.”

DeJohnette used a Sonor ‘Signature’ set for the clinic series, a customised version of which is being prepared for him. He has also used a Sonor Phonic kit for many recordings.

He explained his preference for Sonor drums:

“I like the resonance of the wood; the kit’s also very beautiful to look at, and the shells have a deeper resonance and greater projection. Also, the hardware’s very sturdy and very heavy, so if you can afford to have some friends help you carry it around … but once it’s in place, it’s not going anywhere.

“One of the reasons I switched to Sonor drums is for their endurance – they really hold up under a lot of pressure. They also have a very distinctive sound as compared to maybe a Gretsch or Rogers drum. Gretsch tend to ring a lot – these tend to maintain more of a pure tone, for me, anyway. Over seven years I’ve been playing them, and I’ve grown with them, so I want to continue playing them as long as they make them.”

Naturally many questions were directed to DeJohnette’s technique. How did he develop his left-hand abilities?

“Just a lot of practice. One exercise for that is to practise playing without the hand or fingers around the stick, because the power comes from the wrist. Practise triplets with accents on the first beat holding the stick in this way and that’ll develop the hand as a fulcrum. I’ve developed a thick padding there now, so that I don’t have to grip real tight. It just needs a gentle pressure, so the stick is free to bounce and I can catch the rebound on every stroke. Practise those triplets slow at first, gradually building up speed and power.”

The same advice applied to the rapid ride cymbal work with the right hand – starting slow, turning the beat around and building up speed. Jack has also employed the ride cymbal beat as a means to developing a fast right-foot beat. Rather than always play distinct beats with the right hand and foot in the classic style, he let the bass drum follow the ride cymbal beat.

“I did it slowly at first, gradually getting faster, then tried playing independent of what was happening with the rest of the kit. Try practising ride cymbal beats with your foot, both with the right hand and without it. It depends on your coordination, but I found it the most natural way to develop it.”

The keynote of DeJohnette’s overall approach to drumming, and one often reiterated was the importance of relaxation to allow an uninhibited creative flow:

“When you’re playing real intense music, the tendency is to tighten up from the emotion, but all that does is cut off circulation to the parts of the body that need blood and oxygen. Also you don’t want to tighten the muscles and get cramp, so the obvious thing is to aim for the reverse – the right mixture of tension and relaxation. Then you can play for a long time intensely or quietly. When your body’s relaxed your ideas can flow, and you don’t have to worry about getting tired. I get a lot of power from keeping my breathing slow.

“Once I get something down that I’ve been trying to do for some time, I invariably try and forget about it, switching onto automatic pilot. I don’t want to have to think about what each hand is doing. Instead I try and create a spontaneous dialogue between my hands, feet, mind and emotions. The subconscious takes over and I can be more spontaneous.”

Melody is fundamental to DeJohnette’s conception of drumming, and a question about drum tuning brought a lengthy response that illustrated DeJohnette’s view of the role of percussion within the ensemble – which goes far beyond simple timekeeping.

“Tonight the tuning hasn’t been critical since there are no other instruments, but there are various ways of tuning that I use. These Sonor drums have dampers fitted that allow you to control the ringing so that you can get just the number of overtones you want.

“Drums can be tuned to a scale, a major triad, diminished scale, fourths, or sometimes I just tune them in relation to each other without the piano – say descending in minor thirds or seconds.

“One interesting thing about tuning in relation to an ensemble is that if you tune your drums down to get a funky ringing sound, no matter how hot they mike your kit, it never comes across as strong as the other instruments; but if you tune your drums up, out of the register of all those bottom end instruments, then you’ll come through. It’s okay for a recording to tune the drums down, because it’s isolated and they can muffle it or put you in a baffle, but on stage all those low sounds go through the PA and merge together, coming out all muddy without distinction.

“So tuning helps. This is a musical instrument, believe it or not. It’s akin to the piano, but just doesn’t have as many keys – although you can use concert toms and get two or three sets of scales if need be. I tuned this set melodically so there’s always some kind of melody going on. The cymbals to the drum set are like the sustain to the piano, so when I’ve got something going with my foot or left hand I can hit a cymbal here or there to give some connection, some flow to the ideas.

“There are a few other drummers around who try and make the drums sound more melodic too – Max Roach is one of them, and one of my favourite drummers. He’s also a good composer, and one of the first guys to tune drums in the forties and fifties, having studied classical music, classical percussion and timpani. But we’ve still got a lot of progress to make. I’m also trying to bring it more to the front as an independent instrument, not just in accompaniment.”

The next step in DeJohnette’s crusade for the drum as solo voice can be heard in a forthcoming release from ECM by his band Special Edition. It’s titled ‘Tin Can Alley’ — which I’m told is no reflection on Sonor drums.

Report by Mark Gilbert