The obituary by Bob Weir of long-time Jazz Journal critic Barry McRae that appeared in our final printed edition – December 2018 – necessarily covered the facts of a much-admired critic’s life, but perhaps respectfully failed to embrace the sheer personality of the man himself. For Barry McRae was a force of nature, an ebullient and enthusiastic fan of jazz, who wrote like a dream and entertained and informed us all in the process.

His demeanour always seemed to say: “What fun! Aren’t we all lucky to enjoy this great music!”, yet his wealth of anecdotes and stories and his woeful dress sense – an often medallioned chest revealed through a partially unbuttoned shirt – hid a serious intent. Jazz was his passion, even if his income was from flogging gin.

He turned up to most gigs with a new album in one hand and McRae’s Moniker in the other: this was a brown-paper covered, large-format, hardback notebook in which he accumulated signatures and inscriptions from jazz musicians around the world. I was lucky enough to be asked to sign up in Volume Five – I have no idea how many volumes there were, or whether there was a hierarchy of importance, with Billy Bang – one of his many heroes and friends – in Volume One and humble scribes bringing up the rear in Volume Five – but it was a warm and typically friendly gesture from a man whose company you always sought out.

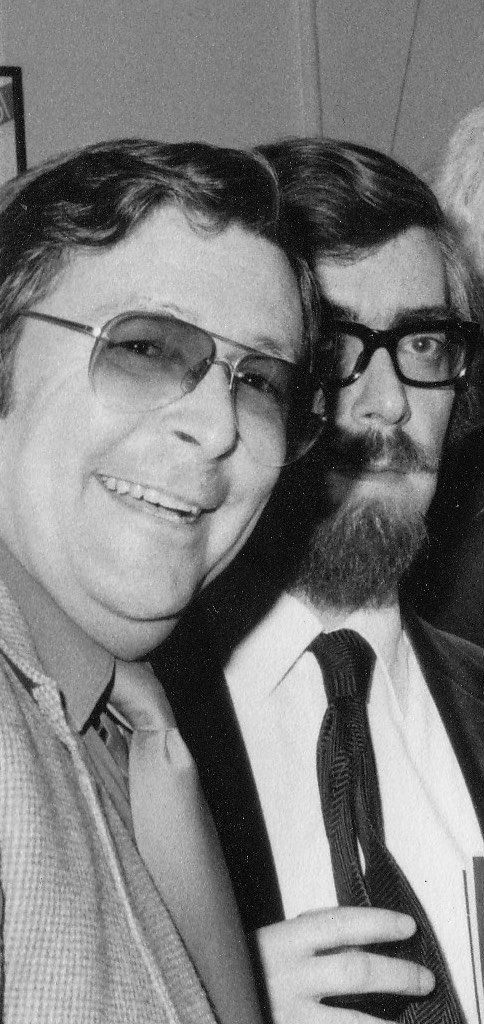

In that company, you were always exposed to his bragging, for Barry was a fund of fine stories. When in New York, often with his great friend the photographer David Redfern, he would stay in the (infamous) Chelsea Hotel. One morning he walked out of his room and into a film shoot, delighted to discover later that it was one of the first promo videos made by the then unknown Madonna. For all his bragging, however he hid a guilty secret, and was suitably embarrassed by the revelation in The New Grove Dictionary Of Jazz that his real moniker was Barrington Donald McRae, no less. When was the last time you ever came across a Barrington in real life?

Barry had no musical training that I know of, and played no instrument, but his criticism was both informed and insightful, explaining what the music was about and why it was important. He never resorted to personal prejudices and ignored all current fads. His ears were as wide if not wider than any modern critic’s: perhaps in this country only Charles Fox and, more recently, Richard Cook, covered the entire waterfront of jazz as he did. To show what I mean, check out these two extracts from The Jazz Handbook, which he wrote in 1987 (and which deserves a reprint, by the way, albeit with new material added to bring it up to date).

“Certain instrumental styles in jazz do not make high technical demands on the player, calling for an economy of delivery rather than a facile show of skill. The obvious example is the tailgate trombone style with its wholly collective role and its position as the hub of the New Orleans ensemble. Rarely asked to carry a melody line, the tailgater is there to add colouration in the form of smears, glissandi and underlying bass harmonies”.

and:

“It was as a solo trombonist on the European circuit that he began to make his mark in the seventies … His vocabulary of voice and trombone accents remained the same, but the scope of his bucolically relaxed improvisation was somehow broader. To prove his links with the distant past, he played his breaks with the alacrity of a Dixielander and delivered his glissandi with the near alcoholic slur of the tailgate primitives”.

Two trombonists of two very different generations and musical styles, Kid Ory in the 1920s, Paul Rutherford in the 1970s, yet Barry summed up both perfectly, understanding their differences yet finding common ground in their instrumental approaches. Whatever he wrote, he made it seem effortless, but, as Bob Weir rightly stressed in his obituary, Barry worked hard at his craft. His reviews were never lengthy or verbose, but in their succinct style told you all you needed to know, and so much more. You read a McRae review to be better informed, even if the musician or band was a stranger to you.

What most distinguished Barry as a critic was that he always listened forwards. Not for him the old styles and revivals, the endless repetition of existing repertoires: he pursued the modern every time. In writing for Jazz Journal, which when he started contributing reviews and articles in 1960 was a very conservative magazine, he produced a monthly series of articles with varied titles – Avant Courier being the most longstanding – that promoted modern jazz in all its variety.

In his outstanding book, The Jazz Cataclysm (1967, reprinted 1985) he wrote his manifesto, an eloquent, informed summary of music in the 1950s that “observes the jazzman’s quest for freedom and especially examines the style of jazz known as ‘free form’. It applauds jazzmen who put personal expressiveness before musical niceties and who, in many cases, suffered unemployment because of their ideals”. Hence the revelatory chapters on Ornette Coleman and the message of the drums, as well as the fine concluding chapter on ‘free form’, including Sun Ra, Don Cherry and Albert Ayler.

One of the reasons Barry gave for stopping writing a few years back was that he heard nothing new in jazz any longer, nothing that interested or excited him. Without the new, jazz meant little or nothing to him. It was our loss, for I am sure he would have found much to critically admire and enjoy as jazz heads joyously into its second century of achievement and adventure.

Some Barry McRae articles:

JJ 02/69: Ornette Coleman – New York Is Now

JJ 05/69: Melody Maker Poll Winners Concert, April 1969

JJ 05/69: Colosseum at Wood Green Jazz Club, 1969

JJ 05/69: Alice Coltrane – A Monastic Trio

JJ 04/79: Derek Bailey / One Music Ensemble