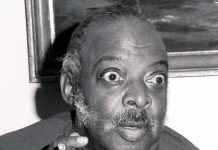

One of the cornerstones of my vinyl collection is a 1958 Decca release entitled Mad About The Man. It could only be a celebration of the words and music of Noel Coward, whose 1932 composition Mad About The Boy has been performed and recorded by singers as dissimilar as Joyce Grenfell and Anita O’Day. That roster includes, perhaps surprisingly, Carmen McRae, whose centenary fell in April of 2020.

She was acclaimed as a world-class jazz singer and pianist and not someone we would immediately associate with the three-quarter time sentiment and veddy veddy Britishness of Coward. Nevertheless, aided and abetted by Ray Bryant (piano), Ike Isaacs (bass), Specs Wright (drums), Charlie Shavers (trumpet) and the subtle charts of Jack Pleis she makes a more than decent fist of the even dozen numbers that comprise Mad About The Man.

The album was one of more than 60 she left us despite a relatively late start. She was in her mid 20s when she cut her first record, a single, in 1946 and it was another eight years before she embarked on what would turn out to be a remarkably consistent series of albums for several labels – Decca, Kapp, Concord, Bethlehem, Atlantic.

Though she never had a hit and/or award-winning album she was ranked firmly by the cognoscenti as the fourth member of the outstanding female jazz triumvirate of Ella Fitzgerald, Sarah Vaughan and Billie Holiday (the latter her principal influence). Just how highly she was esteemed by fellow musicians is illustrated by an observation by Miles Davis who noticed a billboard in San Francisco announcing an appearance by Ella Fitzgerald which referred to her as the “Queen of Jazz”. “If Ella Fitzgerald is the Queen of Jazz”, he growled, “what the fuck is Carmen?”

Born in Harlem and raised in the Bronx she began studying piano at eight in a home filled with recordings of top jazz musicians. In her late teens she became friendly with pianist Teddy Wilson and his then wife songwriter Irene Hitchings who introduced her to several leading jazzmen including Billie Holiday who had a lasting influence on Carmen and recorded an early McRae composition, Dream Of Life, in 1939.

By now an accomplished jazz pianist McRae spent several years in her late teens and early 20s making a name for herself as pianist at Minton’s Playhouse, where bebop was being developed and where she met her first husband drummer Kenny “Klook” Clarke, whom she married in 1944. Keyboard stints with big bands led by Benny Carter, Count Basie and Mercer Ellington (with whom she cut her first record in 1946, Ellington’s own composition Pass Me By – no connection with the Cy Coleman-Carolyn Leigh number with the same title which they penned for Lucille Ball’s Broadway show Wildcat) kept her in steady work throughout the 1940s.

After several years’ equally steady work in Chicago she returned to New York in the early 50s where finally, well into her 30s, she embarked on the vocal career for which she is best known, thanks to a recording contract she signed with Milt Gabler. She went on to garner endorsements such as “Carmen McRae is indisputably one of the greatest vocalists the idiom has ever produced” (Will Friedwald) and “She’s always given me the feeling that she respects lyrics as much as she does music, and that, I think, is the secret of her strength: the balance she maintains between the two” (Gene Lees).

A smattering of album titles should be sufficient to spark warm memories – Torchy, At The Great American Music Hall, By Special Request, Carmen For Cool Ones, Afterglow, Book Of Ballads, Something To Swing About. These are timeless sessions that feature her with every combination from trio to full orchestra, sometimes her own piano and sidemen including Dizzy Gillespie, Mundell Lowe, Joe Pass etc.

A live gig by McRae was a complete experience; not one to suffer fools she thought nothing of pausing in mid-song to give someone a tongue-lashing and then pick up where she left off without missing a beat, witness the poor woman talking at ringside at a gig in Frisco: Carmen leaned down from the stand, fixed the woman with a lava-filled stare and said “Either I’m gonna come down there and you’re gonna come up here or you’re gonna let me finish this song”, and that was one of her milder rebukes.

Which brings us back to Coward. Although his plays are revived constantly and performed internationally, his songs, with the exception of Mad About The Boy, are largely ignored by jazz performers. Yet from the first he has displayed an ability to swing that remains undetected – try playing say Sigh No More, Time And Again, or Half-Caste Woman without the words if you don’t believe me. McRae was astute enough to spot the potential in Coward and parlayed that into one of her finest albums.

In conclusion: we Brits like to claim that Americans have no concept of irony and find themselves floundering in its presence. There is at least one American able to refute that: asked point-blank by The New Yorker for a comment on her notoriously salty public utterances McRae replied sweetly and succinctly “That’s bullshit”.