Purists may feel duty-bound to view John Scofield with suspicion, but they need not worry: Scofield’s music is not a fusion but a natural evolution. To many ears it is a distillation of all that is best in modern jazz – a jazz that has evolved side by side with rock for two decades and borrowed naturally and unconsciously from all that is vital and expressive in both forms.

At 31, Scofield has an impressive curriculum vitae by any standards. He has worked with Gerry Mulligan, Billy Cobham, Gary Burton and Chet Baker, among others, and his vocation of the last three years – his own trio with bassist Steve Swallow and drummer Adam Nussbaum – was interrupted in November last when he joined the Miles Davis band.

In the beginning, jazz was not preeminent in Scofield’s reckoning. Born in Ohio on December 26, 1951, but growing up in Connecticut, he came into teenage just as the Beatles heralded the rock boom of the sixties. At 12 he got his first guitar and played in rock bands – ‘a normal kind of background’ as he puts it. Then he heard urban blues and at 14 started taking jazz lessons from local teacher Alan Dean. His friendship with Dean gave him access to plenty of jazz and blues on record, and he was able to hear live jazz in New York. Among others he saw Muddy Waters, Jimmy Reed, Larry Coryell, Wes Montgomery and an important early model, Jim Hall.

‘The problem with the guitar is you don’t breathe on the instrument. You sit and practise the hardest things – long extended lines – and then sometimes the practice gets in the way of the performance’

Scofield was sure from his mid-teens on that he wanted to play jazz, but even now he finds it difficult to classify his own music: ‘It’s hard to pinpoint anything – the terms are rough. I’m just an exponent of all the elements I’ve listened to, like BB King, Otis Rush and all of mainstream jazz – I’ve made that my real study.’ This eclecticism must be thanked in part for Scofield’s arresting individuality, but there is another more specific reason: ‘I didn’t copy so much from guitar players. Some things I copied right from horn players or pianists. You copy something, never get it quite right, and it comes out a little different. Also, in the sixties there weren’t that many guitar players that were playing the real hip shit, except John McLaughlin, and that was the very late sixties.’

Of course there is nothing new in guitarists copying from other instruments – jazz guitarists from Charlie Christian onwards have done it – but in Scofield’s case, the horn players and pianists were of a contemporary generation: when he talks about ‘mainstream jazz’ he includes Miles Davis and John Coltrane.

One might forgive Scofield for being blasé about post-Christian jazz guitar playing: he spent 1970-73 at Berklee College Of Music in Boston, consolidating technique and theory, and he owns to having served a mainstream apprenticeship from age 15. Certainly he is not uncritical of jazz guitar conventions: ‘One of the problems with jazz guitar players is that they got so much into playing even eighth notes that it became a little boring, a bit like Paganini. We all have that tendency, because it’s hard to do and that’s what you practice. What I like about players like Miles, Lester Young and Parker is that they are very natural. When they hear a long extended line, they play it. They don’t play stuff they don’t hear, and I think that’s important. The problem with the guitar is you don’t breathe on the instrument. You sit and practise the hardest things – long extended lines – and then sometimes the practice gets in the way of the performance.’

Ears weened exclusively on bebop guitar are likely to feel uncomfortable when first they hear Scofield’s playing, but that is not the intention: ‘It’s not that obvious a gesture, but I guess I don’t want to sound straightahead. In improvising, there’s a fine line between being boring and being pretentious. If you’re boring you take the easy route. If you’re pretentious you play anything flagrantly to sound different. I’d like to straddle the middle line and make it sound natural. The subconscious will take care of everything if you can get that flow going.’

‘I just listened to some players who played notes that weren’t in the little book of scales. I tried to emulate that and it became normal, so that now I can’t tell what’s right or wrong anymore – it’s just tension and release’

New listeners might not immediately hear Scofield’s playing as ‘natural’ because he uses unfamiliar dissonances. But there is method in the apparent madness: ‘I really do believe in true melody as opposed to experimentation. A lot of the weird things I play are for the sake of rhythm, and that’s one of my favourite things. I don’t think of dissonance so much as that there are things incorporated in my playing that others might conceive of as dissonant. I just listened to some players who played notes that weren’t in the little book of scales. I tried to emulate that and it became normal, so that now I can’t tell what’s right or wrong anymore – it’s just tension and release.’

The uninitiated will now have gathered that Scofield is not interested in random improvisation; he does not play ‘free jazz’. Although his framework may initially seem so flexible as to be non-existent he is essentially interested in patterned music. Furthermore, although he might criticise the excesses of post-Christian jazz guitar playing, he does not dismiss the basic harmonic material.

‘It takes a long time to learn how to play straight diatonic harmony. It’s funny – at first you think it’s going to hang you up because you can only play uninteresting things, but the more you learn to play on a tune like Stella By Starlight or Confirmation, the more interesting movement you find in the chords. That really takes a long time, to get that together.’

Scofield’s efforts to get it together outside of Berklee began with playing a Chet Baker/Gerry Mulligan reunion gig at Carnegie Hall in 1974. This was followed by a two-year stint with Billy Cobham, which if it did little for Scofield’s mainstream chops, certainly gave him plenty of opportunity to ‘rock-out’. His playing during this period can be heard on the 1975 album Funky Thide of Sings (Atlantic K50189). The music is emblematic mid-seventies jazz-rock, at times tasteful and at times dwelling on lumbering cops and robbers themes. Scofield is featured as rhythm and riff player in typical funk style, and the wah-wah pedal betrays the album’s vintage. His solos are mainly rockish in tone and phrase, but two tracks, Panhandler and Thinking Of You find him overstepping the bounds of rock ‘n’ roll propriety and hint broadly at a musical personality that does not conform happily with generic preconceptions.

After two years of thrashing things out with Billy Cobham (later George Duke and Billy Cobham), Scofield’s next assignment could hardly have been more contrasting. He spent a year (1977) with vibist Gary Burton and both the job and the year were turning points. The job helped him to find general acceptance as a sideman and his leaders have included Charlie Mingus, Ron Carter, Jay McShann and the renascent Chet Baker. An album recorded with Baker in 1977 (You Can’t Go Home Again – A&M Horizon SP 726) again finds him in a fast and funky context on a rejig of Cole Porter’s Love For Sale, which is arranged to feature an extended modal blowing section over a funk bass line, resolving into a straight swinging chorus. This is fusion at its most literal, and while at times it sounds rather incongruous, the solos are worthy. Scofield has come on apace and is now garrulously conversant with his own special vocabulary of maverick notes – those outlandish dissonances that help define his style. This album also shows that not only can he swing with the rest of them, he can do it alone. Rhythmic audacity is intrinsic to his line.

With burgeoning sideman credits, it was not long before Scofield was invited to front his own band. The offer came from Germany in 1977, and Scofield took with him Richie Beirach (p), George Mraz (b) and Joe La Barbera (d). Testimony to the excellence of this quartet can be found on Scofield’s first album as leader, John Scofield Live (Enja 3013), recorded in Munich in November 1977. The enthusiasm of the local audience shows why Scofield has returned frequently to Europe.

It is also an accurate reflection on some superb music. It differs from earlier recorded Scofield in that half the record is devoted to his own compositions and the whole thing has a post-Coltrane flavour. All the players are sympathetic to this cause, and the band have an easy rapport. This, together with the modal emphasis of the compositions, makes for relaxed and expansive playing. Scofield’s Gray And Visceral, with its broody minor key vamp and major release has all the harmonic movement it needs. Some of the best action is in the spaces between the notes, and Scofield’s Milesian bent is most evident here. Swooping, tumbling and climbing back up again, the players avoid modality’s tedium trap and produce plenty of dynamic and melodic variety. Richie Beirach’s Leaving gives us an example of a favourite Scofield device, aptly described by critic Chip Stern: ‘Scofield can be lush and introspective, but he isn’t above kicking over a metaphorical beer bottle mid-rhapsody just for a change of pace.’ So, in the middle of a swinging minor passage, Scofield inserts a bright country blues figure that throws the solo into sharp relief.

A year later, another album was recorded under Scofield’s leadership – this time in the studio. Rough House (Enja 3033) was recorded in Stuttgart in November 1978 by a band featuring Hal Galper (p), Stafford James (b) and Adam Nussbaum (d). It follows modal recipes similar to those employed on the Live album. However, without belittling Richie Beirach’s singular contributions on that record, it must be said that it is Hal Galper’s piano playing that distinguishes Rough House. His inventive, melodic and swinging style can best be heard on the title track, with its Tyner-like climaxes and cascading releases. This track also illustrates Scofield’s storytelling skill, his solo here having some powerful call and response patterns.

Two other tracks show the group’s ability to imbue intrinsically simple harmonies with as much colour as any set of standard changes: Ailleron‘s tension and release lies in the resolution of a stuttering theme into a straight swinging section with Giant Steps type changes, but it is Galper’s Triple Play which proclaims the quartet’s strongest qualities. It has plenty of well-held climaxes and rhythmic variations and some fine solos. Scofield’s solo fields all his best moves: it is considerately paced, makes free use of the blues and rock vocabulary and shows the importance of rhythm in his phrasing. Furthermore, this solo falls across a breathtaking change of time in the sequence – a change which Scofield’s solo line appears to initiate and reinforce. The solo begins over a swinging 6/8 rhythm, which then alternates with 4/4. Eventually Nussbaum picks up the 4/4 strongly on the snare and the whole unit converts to the rock-steady shuffle beat. This apparently spontaneous transition creates a feeling of tremendous resolution after the preceding ambiguity and is for me one of the highest points on the album.

Scofield recorded in a similar context a year later (1979) with Nussbaum and Galper, with Wayne Dockery on bass. The Galper-led album Ivory Forest (Enja 3053) naturally places most emphasis on the leader’s excellent playing, but Scofield can be heard in party mood on the Latin My Dog Spot, going angular and free-ish in parts of Rapunzel’s Luncheonette and essaying his acapella talents on Monk’s Mood.

In the same year, Scofield showed his continuing allegiance to the funk on the Arista album Who’s Who (AN 3018). The very mention of that term might upset some of our older patients, but this is not the bitter commercial pill they might suspects. Simply, it shows that Scofield still values the style and is able to adapt it to his own tasteful design. He is accompanied by Kenny Kirkland (p), Anthony Jackson (elb), Steve Jordan (d) and Sammy Figueroa (pc) on all but two tracks, where he works with Dave Liebman (s) Eddie Gomez (b) and Billy Hart (d), in a post-Coltrane style.

And so we come to the final and most significant phase of Scofield’s career – a phase that in Scofield’s own opinion has produced the first albums he has been happy to listen to again. This seems logical when one remembers that the John Scofield Trio, formed in 1980, presents Scofield matured, his various influences smoothly integrated. The trio’s three albums feature Scofield playing Scofield, rather than Scofield playing Coltrane, Miles, BB King, Jim Hall or any other obviously derivative style.

Steve Swallow plays electric bass in the band, but as Scofield explains, his importance is almost extramusical: ‘Swallow’s been one of my major influences. He’s one of the best writers around, but he’s really pulled towards me writing tunes for this band, because he wants me to develop as a writer – a little bit like my guru. I write the music for us to play together, with Swallow in mind from the inception.’

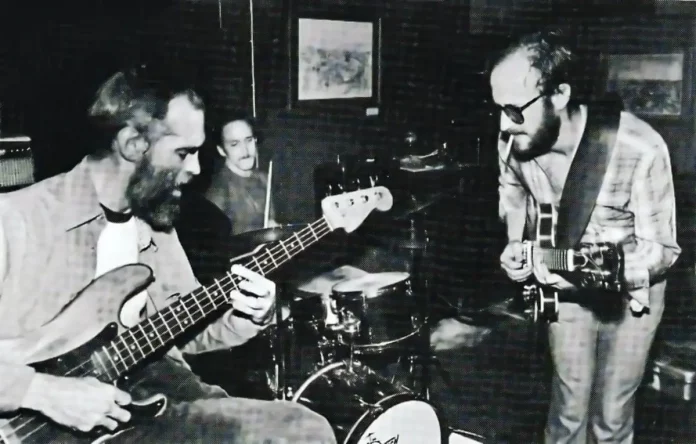

The trio’s originality is evident on their first album, Bar Talk, recorded in August 1980 (Arista Novus AN 3022). It’s not rock, not funk, not straightahead solo-over-rhythm. In every respect the band pulls together as a trio unit, the three elements bound into an inimitable whole. Nobody coasts and rarely does anybody play straight when they can bend or accent time and melody. The six Scofield compositions demand this flexibility, so that, for example, Swallow rarely walks the bass line – more often he is strumming chords or staggering the rhythm. This happens in conjunction with the excellent drummer Adam Nussbaum, so that the two together set up patterns of ebb and flow in the rhythm section. Scofield’s work is superb, and his solos on Beckon Call, New Strings Attached and Fat Dancer all serve to illustrate his kaleidoscopic brilliance.

The trio’s most recent recordings derive from a three-night stand in a Munich club in December, 1981. Shinola (not an oriental guru but a brand of shoe polish) was released in 1982 on Enja 4004 and features generally more subdued material than its predecessor. Five Scofield originals are joined by the Jackie McLean tune Dr Jackle. The overall atmosphere is balladic and the album requires some pretty close listening. The programming could have been stronger, with alternation of ballad and driving pieces; as it is things are rather lopsided. Nevertheless, the medium-paced Rags To Riches is full of typical Scofieldian ambiguities and red herrings, Dr Jackle is a good hard bop blow, and the power held in check through most of the album is released in one salvo on the maverick Shinola, which is unambiguously 1980s music. One suspects a certain irony is intended in this overblown rock rave up, but whatever, Scofield produces climax after climax, only narrowly delivering order out of chaos – exciting stuff!

Shinola’s sister album, Out Like A Light (Enja 4038) is better programmed and generally more outspoken. Last month’s Jazz Journal carried a review of this record that was almost complete; it omitted only to mention that Out Like A Light is the best illustration yet of Scofield’s prismatic talent. His solo on the modal Holidays displays the colours of all his influences refracted into the natural and coherent single shaft of light that is Scofield’s distinctive sound.