Sixty-two years on from Ornette Coleman’s startling album The Shape Of Jazz To Come, the shape of things in Miguel Zenón’s tribute is Coleman played with more virtuosic relish. There’s also a concentration of tonal range in having tenor saxophonist Ariel Bringuez replacing TSOJTC’s cornettist Don Cherry, who played trumpet on Coleman’s Something Else! the previous year. What Zenón doesn’t have, in accordance with Coleman stricture, is a chordal instrument.

Coleman’s flight from “imprisoning” chord sequences, especially the chords that changed almost before you’d realised they’d been struck, seems to have been not a foretaste of the future but a way out that has taken few other forms. One of them was “freedom” without the responsibility of knowing when enough was enough; another was the liberty to appropriate other genres. But had Coleman’s structural freedoms been simply replicated, as they are on this album, then the shape of jazz to come didn’t change much. Jazz has changed, however – a lot – and more might be ascribed to Coleman for that than is customarily acknowledged.

Zenón clearly understands that in dispensing with some features, Coleman had to find replacements. One is the cohesiveness that results from the way the musicians build contrapuntally on the responses of the others in the group. On the second track, appropriately titled Free, the two saxes set off in voluble conversation, with the motoring bass and drums (Demian Cabaud and Jordi Rossy respectively) supporting lengthier solos by the saxes in The Tribes Of New York. The head of Free, too, also illustrates how virtuosity can more easily admit humour as the frantic dialogue powers down and the quirky intro returns.

That Coleman’s “free” revolution was not that far removed from the style from which it sought to extricate itself is evident in Giggin’, with its bebop-like theme. The lengthy solos of Zenón and then Bringuez have logic, an intrinsic sense of swing, and a recognition of pedal-point modality. Dee Dee shows how structure, to be made variable in this edgy style of jazz, often involves a lot of work, the whole chart a seemingly endless intertwining of alto and tenor taken at a lick. All the tunes are chosen from different Coleman recordings. Broken Shadows, from the 1971 album of the same name, here involves alternate swopping of the theme by one sax as the other festoons around it and Cabaud’s arco bass threads a way through. Rossy throughout is attentive to the rhythmic patterns set up by the two principals; he and Cabaud, however, might have been allowed to do more with their release from constraint.

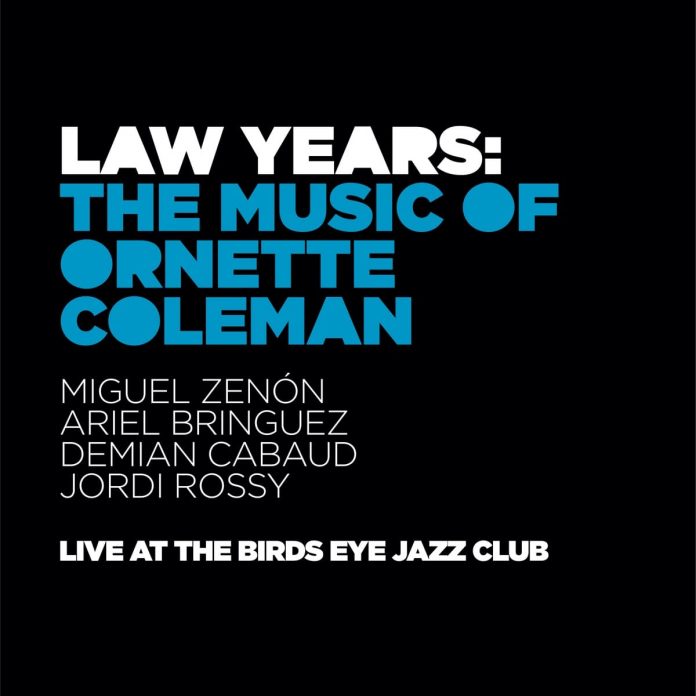

This is an international quartet – Zenón (from Puerto Rico), Bringuez (Cuba), Cabaud (Argentina), and Rossy (Spain) – playing for the first time and after a residency at a European club, the Bird’s Eye in Basel. As both a warm tribute and mastery of a style it could hardly be bettered.

Discography

The Tribes Of New York; Free; Law Years; Giggin’; Broken Shadows; Dee Dee; Toy Dance/Street Woman (58.11)

Zenón (as); Ariel Bringuez (ts); Demian Cabaud (b); Jordi Rossy (d). Switzerland, May 2019.

Miel Music 7 (digital only)