The days when drummers were the people in the background who just kept time are way past. With men like Art Blakey, the percussionist was liberated, and it became possible for a musically literate drummer to lead a group. One of the most impressive examples in this country is Jon Hiseman’s Colosseum, of which Barry McRae (May 1969 Jazz Journal) has said, ‘Hiseman is undoubtedly the leader. Something of a musical bully, he edges his men into the areas he requires and, in so doing, turns his group into a pop version of the Jazz Messengers.’

Barry’s remark brings up another point about Colosseum – the question of rock music and its relevance to jazz. This is an issue which has been the subject of many heated comments, in this magazine as elsewhere, and the reader might well think that all the arguments for and against had, at this stage, been well-voiced. Nevertheless the fact that a musician of the stature of Miles Davis is currently absorbed by pop techniques surely demonstrates that this is no peripheral issue, but one of the central questions of today’s – and tomorrow’s – music, which cannot be hastily dismissed.

Hiseman, who comes from a family of musicians and entertainers, began his career by playing ‘washboards, paint-cans and things’, though by 1961, when still at school, he had a set of drums that ‘roughly resembled a modern kit’. He played the piano and violin, from which he gained a knowledge of musical rudiments, but he soon realised that his chief interest was the drums. His style developed by listening to records and then trying to imitate what he heard. He must have gained his brilliant technique quite early, for he claims that after he’d mastered some phrases he found that two drummers were used on the record he was copying.

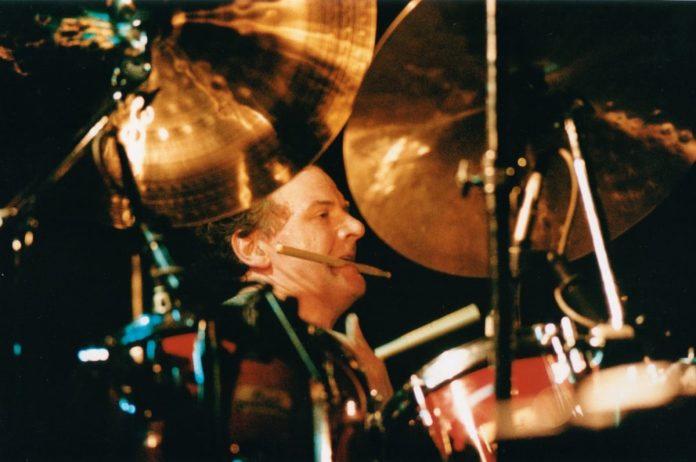

He dislikes using the hi-hat for regular timekeeping, as is favoured by most post-bop drummers, and so found that he wasn’t using his left foot much. He experimented with two bass drums of different tones, but later settled on his present arrangement of having them both of the same pitch, in effect using the two drums as one. Hiseman’s style is very fast and hard hitting, though its loudness should not be mistaken for lack of subtlety. He succeeds in producing a variety of tone colours while maintaining a firm beat, whether explicit or merely implied: ‘I am not interested in freedom for its own sake. I just don’t want to go tick-tock all the time. Actually, I keep time – in my head anyway – even in what sound like completely free bits. But the point is that time is too limited in its emotional range. And I like to communicate emotion. I can do this by building tension and relaxation, by making some bits edgy and getting others to float along. You can produce tone-colours that either sharpen the music or else blunt it.’

Hiseman is a strong player who needs to work with equally powerful musicians. ‘Good jazz must be a dialogue – a group should not be dominated by one musician, least of all a drummer’, he explained to me recently, going on to describe how difficult he found it searching for people stronger than himself. His teaming up with Mike Taylor was an ideal partnership. Taylor’s stark, austere piano style and Hiseman’s explosive drumming complement each other perfectly, as the LP by the trio (1) shows. Around the same time (1967) Jon took over from Ginger Baker in the Graham Bond Organisation. He was delighted to work with Bond and says that the band which included Dick Heckstall-Smith (later to become an important voice in Colosseum), was ‘the strongest thing I’d come across – I was a relative weakling’. Jon’s plans at this time were to work concurrently with Bond and Mike Taylor. The latter was a very underrated musician who did not get many gigs, so Jon could have managed this arrangement quite easily. Taylor’s tragic suicide, which seems to have been brought about by his utter despair that his music was not being accepted or understood, left Hiseman playing solely for Bond.

A period with Georgie Fame followed, which Jon now acknowledges as ‘a retrogressive step’, and before long he was making plans to form his own band. Before getting one together he was approached by John Mayall who was in the process of re-forming his Bluesbreakers. Still intent on having his own band, Jon accepted Mayall’s invitation on a temporary basis, and in the few months they were together looked around for members to complete his own group. During his spell with Mayall the ‘Bare Wires’ album (3) was made, marking a high spot in Mayall’s career as well as bringing Hiseman to the attention of a wider public. When this particular version of the Bluesbreakers split, Jon took with him sax-player Dick Heckstall-Smith and bassist Tony Reeves, and teamed up with keyboard man Dave Greenslade and a young singer/guitarist to form Colosseum. The reason for using a heavily amplified instrumentation was not so much because Hiseman wanted to make it on the pop scene, but because it is only with such a line-up that he can put everything into his drumming without completely dominating the music. The first album (4) shows the band in its early stages: as with Jon’s own playing the physical impact is exhilarating but does not obscure the inventiveness and subtlety which can only come from years of experience and hard work.

Good as the group’s debut record was, it was the combination of their live performances and the second LP, ‘Valentyne Suite’ (5), which brought them deservedly wide acclaim. By this time they had really found their style and were playing better than ever before. The title track, a suite in three movements, remains the best thing of its kind to have been recorded by a British group. Regretfully lack of space precludes a detailed analysis here – suffice it to say that it is cleverly structured, giving a variety of contexts for improvisations from all members of the band. The composition has sufficient variety to be interesting in itself, yet remains open enough for the musicians to have a good blow – which they all do. It was interesting and exciting to see how, over months of live performances, the suite grew and developed.

Apart from all the work with Colosseum, Jon found time to be active in other musical settings. He played on Jack Bruce’s album (6) which, together with Colosseum’s ‘Daughter of Time’ due out this month (November), he considers the most important thing he has done. And, of course, we should not forget his work for the New Jazz Orchestra. Jon and Neil Ardley have been the organising forces which have made this one of the best of the semi-regular big bands, and the records (7) and (8) demonstrate Hiseman’s skill at propelling a large ensemble.

He looks like being busy for some time yet. Colosseum has just undergone personnel changes and is about to embark on a tour of Britain and Europe. During this time Jon hopes to be able to compile tapes for a live LP. He could probably afford to retire tomorrow, but he assures us there’s not danger of that: ‘We just enjoy working’, he says.

Recommended records

(1) Mike Taylor Trio – Trio, Columbia SX6138 (1967)

(2) Graham Bond – Solid Bond. Warner Bros 3001 (1966)

(3) John Mayall – Bare Wires. Decca SKL4945 (1968)

(4) Colosseum – Those Who Are About To Die Salute You. Philips (1969)

(5) Colosseum – Valentyne Suite. Vertigo V01 (1969)

(6) Jack Bruce – Songs For A Tailor. Polydor 583 058 (1969)

(7) New Jazz Orchestra – Western Reunion. Decca LK4690 (1965)

(8) New Jazz Orchestra – Le Dejeuner Sur L’Herbe. Verve VLP 9236 (1968)