Morrissey-Mullen Band / Holdsworth and Co / Paraphernalia

Starting with Morrissey and Mullen, the programme seemed destined to a warm response, and although I found their material a little drawn out and remeniscent of the Crusaders at times, the playing was competent throughout.

Holdsworth and Co. proved to be the shock of the afternoon, judging by the hasty retreat that half the audience in the stalls made after the first number. This harsh treatment of a band on their London debut could well be put down to the complexity of the music attempted by the trio, as well as the virtually inaudible vocal from Holdsworth. However, I sat and watched the whole set, and ultimately found it the most interesting of the afternoon. Special mention must be made of Gary Husband’s fine piano solo on the Gordon Beck composition Stop Fiddling which also featured great playing from bassist Henry Thomas. Their last number, Where is One, demonstrated their potential beyond any doubt, and Holdsworth showed his guitar technique to be going from strength to strength.

Barbara Thompson and Paraphernalia seem very much in vogue at present, with a successful album, “Wilde Tales”, and recent television exposure to their credit. All of their set met with rapturous applause and I felt special mention should be made of the flute on Summer Madness and the excellent bass from Dill Katz on Frilly Bolero. I did, however, feel at the end of the day, that all three bands had little to do with fusion, jazz rock, jazz funk, whatever label must be applied, and that whilst Thompson strived for pleasant melodies and is quite obviously highly proficient at her art, most of her music is rather cold.

Mitt Gamon

Company

Almost two weeks of jazz came to a successful conclusion with three concerts by Company. They featured a new name on the roster in George Lewis, and gave notice that their own record company will be issuing a permanent reminder of the events that took place. As always with Company events, the formula changed each night. I caught the final performance and it proved to be an unqualified triumph for all concerned.

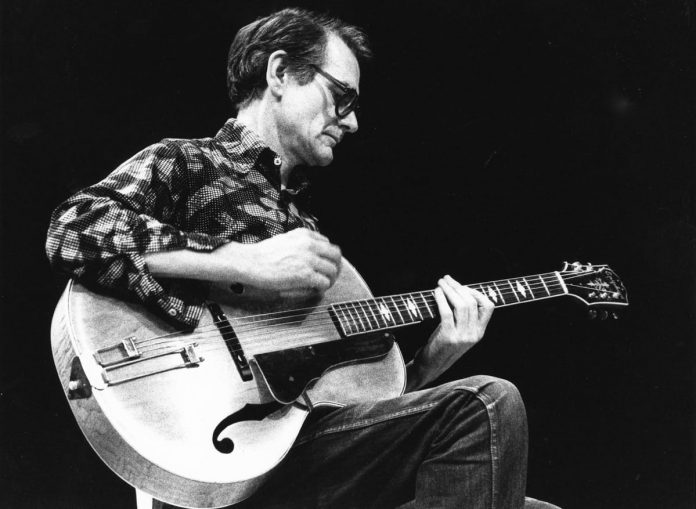

Records by the young trombonist had perhaps prepared us for a man concerned with this composing skill and the more formal aspects of the music, yet he fitted into the free flowing atmosphere of Company with ease. He shared the opening duo with guitarist Derek Bailey and the contrast between his softly contoured free development and Bailey’s jaggedly provocative line was ideal. The Englishman wisely chose the acoustic instrument in this set and, with his note dying rapidly he achieved an exaggerated definition and offered an urgency that worked well with the slurring legato of the horn.

The second set teamed the sophistication of Dave Holland’s educated bass with the probing, rhythmically unpredictable saxophone of Evan Parker. It turned out to be another stimulating contrast of styles, with the soprano/cello duet a particular success, and with Parker settling for his effusive rather than his more fragmented line.

The final set featured the full quartet and, even more than others, it captured the spirit of Company. It produced sparkling, four-voice polyphony with no individual effort of more value than the others. In fact, it provided a fitting end to a festival that had its early administration problems, but had managed to come through, thanks to group effort and a brave as well as sensible programming policy.

Barry McRae