In a toilet at Billy Berg’s club in Los Angeles, a man named Dean Benedetti is waiting to make a secret recording of Charlie Parker’s solo during the first set of the evening. When a number ends without a Parker contribution. Benedetti searches for the altoist and finds him surrounded by the remains of a meal in the dressing room, in the act of consuming a second helping of the same. A waiter arrives to replenish the booze Bird is using to wash down the food. He has words about his lateness with the club owner. He unpacks his horn, and finally makes a flamboyant entry into the clubroom and plays a triumphant solo on the last tune of the set.

These events are from the first chapter of ‘Bird Lives!’, and they add up to the most effective appetiser for the main course that I’ve ever read in any book. Russell makes brilliant use of the novelist’s technique of accumulated detail: the Mexican food Parker’s eating is faithfully described, we learn minute details of his appearance, the unpacking of the Selmer alto is lovingly dwelt on, and the build-up is exciting enough to lend the description of Bird’s eruption into the club nearly as much impact as his actual playing. And it’s this urgent quality of the writing that makes Russell’s book so remarkable; stages of Bird’s career are described in terms heavy with anticipation, in an exhaustively detailed and close-packed style that is informative while making respectable once more that hoary publisher’s blurb stand-by, ‘compulsive reading’. Try for instance the account of the nights the young Parker spent in Kansas City’s Reno club, eyes glued to Lester Young’s fingers.

The book represents, probably, the furthest point along the road to understanding Charlie Parker that anyone’s likely to reach; to be more conclusive we would need the man himself among us, and Russell has had to stop short at explaining the dichotomy between the heights Bird reached in his art and the mess he made of his life. Attempts were made while he was still alive, but Russell counters the question ‘Psychotic or psycho-path?’ by questioning the validity of the ‘psychiatry game’ when applied to black Americans. It’s a question that urgently needs attention, and it’s not one that can be answered by pointing to racialism alone; plenty of white Americans have ended up like Parker, and the implied over-simplifications of Parker’s problems would seem to be manifestations of the white liberal deference to all things black and beautiful which also emerges when Ross expresses the opinion that ‘with very few exceptions (Beiderbecke and Jack Teagarden, perhaps) white players have been imitators, codifiers and exploiters’.

One must resist the temptation, though, to use small parts of the book as pegs on which to hang long and dubiously relevant arguments; ‘Bird Lives!’ is neither a sociological treatise nor a critical history of jazz, except inasmuch as in either case an examination of the particular inevitably illuminates the general to an extent. Russell’s aim has been to paint a portrait of one man. and if he hasn’t managed to fully explain his character he’s managed to make us believe that such a complex man existed, which previous, sometimes contradictory reminiscences have failed to do convincingly. ‘Bird Lives!’ is certainly, as Stanley Dance remarked in our April issue ‘the best biographical or auto-biographical work yet published about a jazz figure’, and I haven’t really done it justice in this short space; it’s very, very highly recommended.

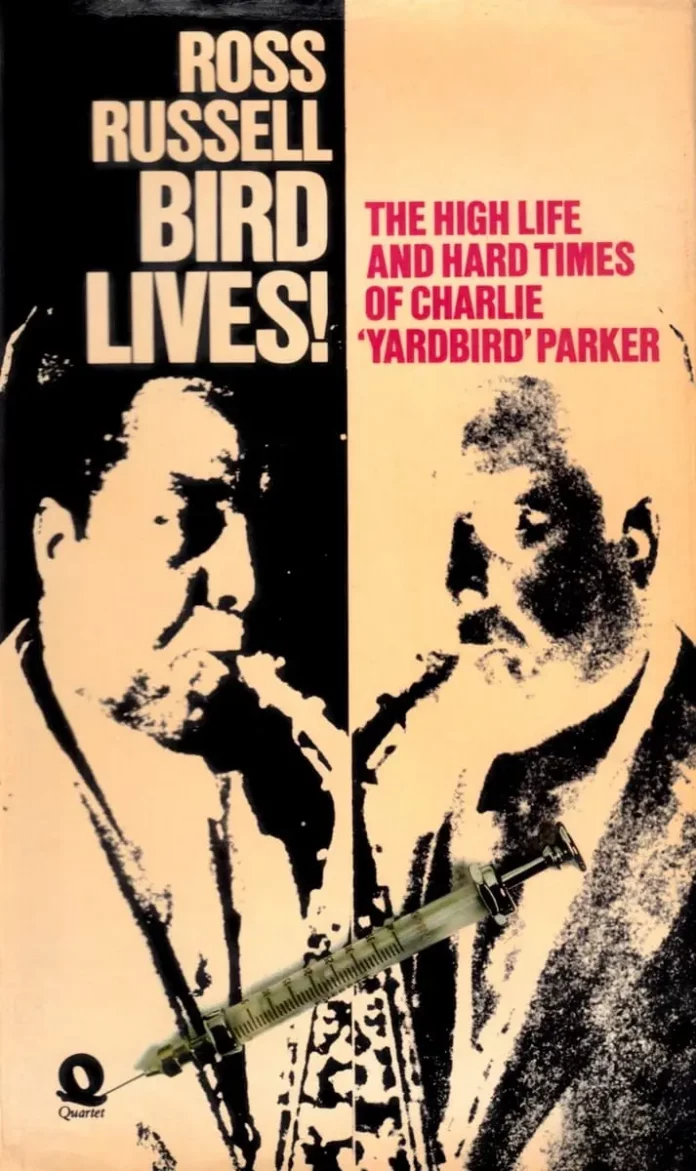

Bird Lives! by Ross Russell (Quartet Books, £3.75 casebound, £1.75 midway, 404 pp, illustrated)