This is one of a series of taped interviews with musicians who are asked to give a snap opinion on a set of records played to them. Although no previous information is given as to what they are going to hear, they are, during the actual playing, handed the appropriate record sleeve. Thus in no way is their judgment influenced by being unaware of what they are hearing. As far as possible the records played to them are currently available items procurable from any record shop.

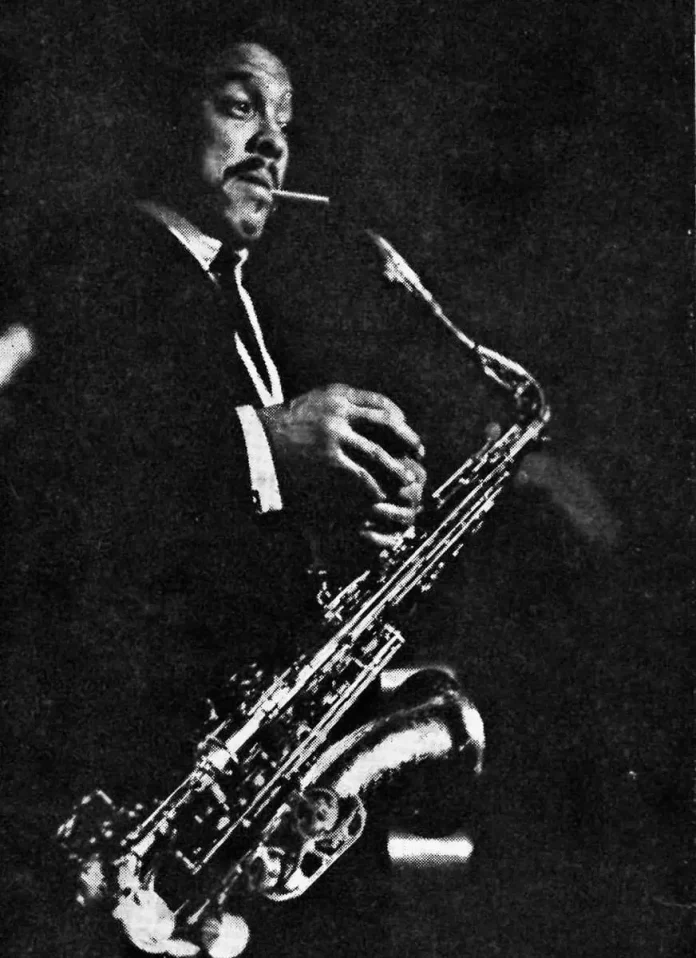

A born and bred Chicagoan, Johnny Griffin is a tenor player whose style is very much in the tradition of the musicians from the Windy City. Possessor of a fantastic technique and a prodigous imagination, Griffin is one of the best to emerge from what has been called the hard-bop school. A highly humorous character, Griffin enjoys life to the full – and jazz being a very great part of his life, he enjoys that as well. Has worked with Lionel Hampton, Thelonious Monk, Arnett Cobb and of course Art Blakey. – Sinclair Traill

Cobb’s Idea. Arnett Cobb. Vogue EPV 1054

I’d know that sound anywhere. Arnett was with Lionel Hampton when I was with the band. And what a parade that band was; I took over from Dexter Gordon, and we had some wild times. Arnett and I used to stage some ferocious tenor battles out front – crowds used to love it. Then I left Lionel and when I returned Arnett had also left. Then in 1951 I joined Cobb’s own small group, playing baritone and only sometimes tenor.

Shine On Harvest Moon. Coleman Hawkins-Ben Webster. Blue Saxophones. Columbia 33CX 10143

Ben and Hawk. Well as far as I am concerned it was Hawk who first gave the saxophone its legitimacy. The tenor in particular before Hawk took it up had been looked upon rather as a joke – an object of buffoonery. I know that Hawk himself says there were others before him, Bud Freeman and I see here he mentions Happy Cauldwell – but as far as I am concerned Hawk was first! As far as Ben is concerned, when I first started playing it was on alto saxophone and I played much in the manner that Ben Webster used. I played very rough and gruff, and growl – very forceful. That was on the tunes with any tempo to them – on the slow ones I leaned more towards Johnny Hodges. I was just a kid of course. And that was the way I played until one day I heard a record by Charlie Parker. I was around sixteen at the time, when someone played me that Hootie Blues by Jay McShann. And there was an alto solo by Charlie Parker that completely turned me round. Funnily enough no one knew then who it was playing that solo, but I remember it so clearly. It really stuck in my mind for it was one of those things that affects the whole course of one’s life.

Mood Indigo. Thelonious Monk. Monk Plays Ellington. Riverside 12-201

I’ve worked with Thelonious twice. First time at the Beehive in Chicago, that was in 1955, along with Wilbur Ware and Wilbur Campbell, and then again in 1958 at the Five Spot in New York. But I’ve been knowing Thelonious many years before then. From 1948 to 1950 I spent a deal of time around Thelonious and Bud Powell and Elmer Hope in New York. I was paying my New York dues at the time, and so I spent most of my days, and nights, listening to the pianists. I like listening to piano and I didn’t want to listen to the saxophonists too much as I didn’t want to be over-influenced by the Charlie Parker faction, who had already influenced me greatly. I didn’t want to listen too much to Lester Young, Coleman Hawkins, Dexter Gordon or Don Byas. They were all very influential to me, but I didn’t want to overdo it, so I spent my time with the pianists. Thelonious, Bud and Elmo were great friends and were always together, so I and Walter Bishop used to hang around them all the time. Sometimes I’d take time off and go and listen to the trumpet players, like Fats and Diz, but I shied away from the saxophones. I was also lucky enough at that time to be able to listen to the master, Art Tatum. Thelonious, you know, always had a running joke with me. We’d be sitting around all feeling pretty good and Thelonious would say: “I used to play just like Art Tatum, you know, but it just wasn’t my style to play that way.”

20 Ladbroke Square. Buddy Tate-Clark Terry. Prestige SVLP 2014

I knew Clark before I ever even had a union card. I was just a kid playing and maybe making a dollar for the night somewhere – at the Vincent Hotel in Chicago, that’s where it was – and Clark he was on leave from the navy band. We was playing this date and this guy in navy uniform he comes up to the stand and says can he sit in, and we said fine – and it was! Up to that time I had never seen any trumpet player use a hat to muffle his horn, but Clark used his sailor hat on the bell of his trumpet and got a different sound – he knocked us all out that night. Otherwise than being a wonderful musician, he is such a beautiful person. If you have a record date in New York, and want a brass choir or anything, just ring Clark Terry and he’ll fix it; no trouble. He arranges so many jazz dates in New York that you can almost call him a jazz record-date contractor. His own style of playing is so very definite, and so very different. Strong, yet full of delicacy, and in addition to making a different sound, don’t forget that Clark has a different approach – and that’s really something.

Tate sounded good on that record, but I don’t know too much about him. I know him of course, but our orbits haven’t crossed too often. I heard him with the Basie band, but back in Chicago he didn’t have the prestige that Hawkins, Ben Webster, Don Byas, or Lester Young had. But they were the people who overshadowed most of what was happening in those days. I myself was very influenced by Don Byas, for the man had such a colossal command over his instrument that he affected me in almost the same way that Art Tatum did. I hope to meet him next week, the first time since 1946! My friends who have returned from the continent tell me that he is still playing as fantastically as ever – I am certainly looking forward to hearing him again. You know Don, like Johnny Hodges, plays so easily that he gives one the impression that he doesn’t care. But it isn’t true! I’ve seen that man play – he’s tricky like that; I’ve watched them both and they’ve played so well for so long, they’ve just got it – that’s it boy got it! I remember one night in New York.

‘Don [Byas] was stoned out of his mind; could hardly hold his head up. . . He tells some friends of his to pick him up and place him carefully on the low bandstand and to hand him his instrument. Which thing they proceeded to do. Well Don started to play and it was like something I have never heard before – fantastic!’

Lucky Thompson, you know, always wanted to play more saxophone than Don Byas; well he came in a joint one night when Don was stoned out of his mind; could hardly hold his head up. So Lucky decided it was his night and he gets up on the bandstand and plays beautifully, and you know Lucky Thompson can really play! But Don Byas, he tells some friends of his to pick him up and place him carefully on the low bandstand and to hand him his instrument. Which thing they proceeded to do. Well Don started to play and it was like something I have never heard before – fantastic! Stoned as he was, he played the most tremendous tenor I have ever heard. And poor Lucky, who don’t drink or smoke or anything, he just shrugged his shoulders and said with a smile: “Just you listen to that drunken bum there – nobody can ever beat him!”

Pennies From Heaven. Frank Sinatra-Count Basie. Reprise R 1008

He’s a great tenor player is Eric Dixon – ole Big Daddy they call him. You know every time I hear him I think he should be with the Ellington band, for he and Paul Gonsalves have such a close affinity in their approach to jazz. That Don Byas melodic approach to jazz. Benny Golson has it too. There is not much tongueing done, it’s more loping. I like to tongue – to push out the notes if you see what I mean. But they like to play with that fine melodic tone, it is almost a sweet tone – it’s a different approach. I love it, but I don’t play that way. Sinatra, well he’s really something isn’t he? Not perhaps a jazz singer as such, but a fabulous performer and such a lovely person. The Basie band, I feel they don’t get much chance these days. They have been more or less relegated to being a dance band. I think it happened ever since Joe Williams was there singing his Everyday Blues. They became more of a dance band than a jazz band. It’s not like the Basie band of old, who used to get up there on the stand, make up some arrangement and then go! There was a wonderful spirit of continuity there, which to me is such an important part of jazz. Of course they are still a very good band, a very good band indeed, but they have been forced by circumstances to become rather more commercial than they were in the past.

Mademoiselle De Paris. Duke Ellington-Midnight In Paris. CBS BPG 62120

Well, there’s the all-time, all-time great! His perception and mastery of construction is quite unique in itself. He is able to take a tune, an ordinary tune like that and treat it with a depth that no one else would ever dream of. He can take an artist and put a dressing around him that puts him in his true perspective – that really sets him off to his best advantage. Duke Ellington, and I must include Billy Strayhorn, they can both do that thing. Geniuses, both! I have listened to that band and have heard them play the same tune, the same arrangement night after night, but it never sounds the same, it is always something fresh. Of course the core of that band, the men who have been with Duke for so many years, they know each other so well that they can always match what the other is playing. They may not talk to each other, but they have such a sympathy with each other musically that they are able to change those arrangements around without any preconceived plan. Duke just sits there and directs from the piano and he can alter that sound by the smallest alteration of a piano note. And the band instinctively know just what to do and when to do it. The only other big band to really excite me was that big band that Dizzy had, that was a wow! But Duke’s music, like the classics, doesn’t date – you just can’t date it. Other bands play period music, their older arrangements sound that way – but not Duke. In a hundred years from today, that tune you have just played will sound as fresh as it is now. The other person who springs to mind in the same connection is Thelonious Monk – his music is also to me quite dateless. Actually, you know, Thelonious and Duke Ellington have a tremendous lot in common. And I mean not only their approach to writing jazz, but also their approach to the piano. Just wonderful.

Are You Real? Art Blakey. Blue Note 4003

Art Blakey, ah!! Well, what can I say about Art Blakey than he is one of the most dynamic, fantastic, extrovert people in existence. A tremendous percussionist and a wonderful person lo work with. When I was working with him we always had something in common – a war! Those fantastic pressure rolls of his used to blow us front line men right off the bandstand. 1 was always telling him to throw those drum sticks away before he made me spit blood! His drumming is just too much. I remember once when I was working with Thelonious – I had been working with him all summer – I was on my way to Birdland where I worked on my night off from Thelonious. Well it was Labor Day, I remember, and I decided to take a real night off, my first night off for four months – I’d get home early and get some rest. You know how it is, hanging around all the time with Art Blakey, Thelonious, Philly Joe and the others, getting juiced and all that – so I decided to have some real sleep. It was Labor Day, a holiday day. Anyway, on my way home I had to pass Art Blakey’s house, so I thought I had better just call in to pay my respects to the ladies of his family, his wife and her sister. I used to room with them before I joined Monk’s quartet and so we were all very close. Well, it was in the afternoon and whilst I was there saying my respects, Art happened to get up. Well we started to argue. Art started telling me how important were the drums and I, feeling rather contrary, kept telling him that the drums were just nothing. This was around 2 o’clock in the afternoon, and we opened a bottle of cognac. By the time Babs Gonsalves joined us, several bottles later, we had got up quite an argument. Well he, quite unnecessarily, decided to become an agitator, and drove us to further points of argumentative discussion, and to help us get really stewed at the same time. So come about 10 o’clock, I had forgotten all about that rest I was going to have, and we were all getting hot. Art he said he’d show me how important the drums were, and I said I could do without drums at any time. Anyway, I told him he was getting old and beyond it and was almost at the stage when he couldn’t hold a drum stick. Well, somehow he got to having a fifty dollar wager as to who would do what to whom on the bandstand. So Art Blakey and I decided to go out and have warfare with each other. We started at a place up Sugar Hill called Branca’s. Ram Ramirez was in there playing and we must have driven him near crazy. I got on the stand and started playing all by myself – it sounded fine to me. Art he just sat at the bar, consuming cognac and saying it sounded terrible without drums! So eventually I left the stand and Art took over and started in to play drum solos. Well we were both pretty loaded by this time, and Art Blakey he suddenly dropped a drum stick. That’s it, I shouted – you owe me fifty dollars! But he wouldn’t pay and anyway we were having fun you understand, so we decided to go to Count Basie’s. Well, Eddie Lockjaw Davis was playing there at the time, and directly he saw us, he said he wasn’t going to let us play. But Erroll Garner was also in there, feeling pretty mischievous himself. So he suggested that Lockjaw and myself should have some warfare. But when Art and myself joined them on the stand, we still had this thing going and so the whole thing was a complete chaos – Art was trying to outdo me, I was trying to outdo him, Eddie was trying to outdo us both, and Erroll he was just laughing himself sore. As I said it was chaos. But we managed to last out ’til closing time and I don’t suppose it sounded too bad. But I never got that fifty dollars from Art, tho’ I am always reminding him that he did drop that drum stick and so I was the winner.