This is flawed music. At those moments when the fusion works, a beauty of both depth and proportion results. But Gibbs, as many of the composers who walk the line between jazz and more formal musics, appears often unable to keep his overall vision of a work in focus.

All too often, valuable motive material is allowed either to lapse undeveloped, as in Tanglewood, or to dissipate itself in extension across greater length than its content allows.

Tanglewood begins with great promise, Pyne’s trombone introducing a theme which strongly evokes the pastoral setting of western Massachusetts in summer. The brass are all sunlight and clear mornings, the forward motion spirited and irresistible. But somewhere in the round of extended solos which follows – Lowther’s lyricism being a standout – the thread is dropped. The piece ends inconclusively in the bleatings of Roberts’ tenor, as though Gibbs had been unable to make up his mind how to resolve it, or had somehow lost the central idea with which he began.

After the meaningless bombast of Fanfare, cello and strummed guitar evoke a hauntingly melodic frame of reference for Sojourn. But that is all it is; the content remains essentially static, is extended rather than actually developed, and finally slips away into directionless twitterings by the reeds. Again, promise unfulfilled.

It is only with Canticle, commissioned for a July 1970 concert at Canterbury cathedral, that Gibbs introduces, develops and sustains a coherent pronouncement. In an elusive, yet effective way, it seizes the Dasein of the church, on both physical and symbolic planes. It is a work of expansive, brooding beauty, fitfully lit in the blues and reds of stained glass. In its structural balance and very tonal relevance it must be counted a major work, one on which Gibbs can be judged. Favourably so.

The set ends disappointingly with Five, a jazz-rock excursion for Spedding which struck me as a pointlessly repetitive bit of space-filling, coarse after the majesty of Canticle.

Gibbs will achieve in time the balance and consistency of focus which are the hallmarks of a major composer. If there was any doubt before that he is certain to grow into such stature, Canticle should be enough to dispel it. For that work alone, this is a record to own.

Discography

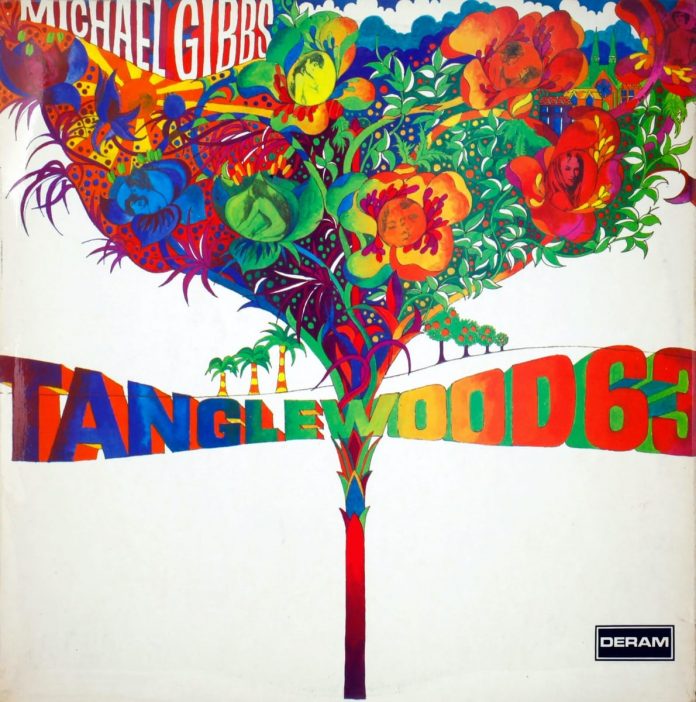

Tanglewood 63; Fanfare; Sojourn (24 min) – Canticle; Five For England (21 min)

Collective personnel: Kenny Wheeler, Henry Lowther, Harry Beckett. Nigel Carter (tpt); Chris Pyne, David Horler, Malcolm Griffiths (tbn); Dick Hart, Alfie Reece (tubas); Tony Roberts, John Surman, Alan Skidmore, Stan Sulzman, Brian Smith (reeds); John Marshall, Cllve Thacker (dm & perc); Frank Ricotti (vb); Chris Spedding (gtr); Roy Babbington, Jeff Clyne (bs/elec-bs); Mick Pyne, John Taylor, Gordon Beck (keyboards); Tony Gilbert, Michael Rennie, Hugh Bean, George French, Bill Armon, Raymon Mosyley, Geoff Wakefield (vn); Fred Alexander, Allen Ford (celli). London, Nov. 10/12, 1970, Dec. 2/23, 1970.

(Deram SML 1087 £2.19)