Given the rough ’n’ ready quality of early sixties Motown recordings, it’s a miracle that anyone should have been able to decipher the playing of then unknown bassist James Jamerson. But apparently fledgling bassists around the world tried to nail the bottom end of the stream of r’n’b and soul singles spilling from Berry Gordy’s primitive Detroit studio. And now, thanks to Dr Licks, we can hear why. This fascinating biography and analysis handsomely augments the growing evidence of Jamerson’s enormous gifts and justly canonises him as a pioneer of the electric bass and probably its most influential player.

‘If, as Earl Van Dyke says, much of Motown’s material was ‘crap’, it was frequently redeemed by the work of its jazz-loving rhythm sections, and in particular by James Jamerson’

Much of the colour and character of Jamerson’s action-packed lines derived from his early immersion in jazz. Like key Motown pianist Earl Van Dyke, he wanted to be a famous jazz musician and began his career on the upright bass before switching reluctantly to the electric – an instrument he grew to love – around 1961. One of his first models was Ray Brown, and he remained a lifelong fan of the Oscar Peterson trio. He also jammed and studied informally with such Motor City jazzers as Hank Jones, Barry Harris, Kenny Burrell and Yusef Lateef. It was a collision between this apprenticeship and the back-beats of Motown which led Jamerson to a novel synthesis. As Dr Licks observes: ‘Gone were the stagnant two beat, root-fifth patterns that occupied the bottom end of most R&B releases. Jamerson had replaced them with chromatic passing tones, Ray Brown style walking bass lines and syncopated eighth-note figures – all of which previously been unheard of in the popular music of the late fifties and early sixties.’

Jamerson became an integral part of the Motown sound, and by the late sixties, when Motown was the biggest black-owned company in America, he enjoyed a $52,000 a year retainer plus overtime, bonuses and club fees. However, in his success lay the seeds of failure. Proud of his achievements, he was constitutionally incapable of adapting to changing fashions. He knew one patently successful way of playing the bass and saw no reason to alter it. When slapped and popped roundwound strings became the style of the day, he remained resolutely a one finger pizzicato player, the dull flatwound strings on his ’62 Fender Precision often several years old. As Motown expanded, it took on additional bassists to cope with the workload, and though still highly revered, the territorial Jamerson grew resentful and sought solace in alcohol. During the late seventies he fell into a tragic decline, becoming moody, violent, unreliable and finally incapable. He died in 1983, aged 47, after spells in hospital and a mental health centre.

Happily, Jamerson’s magic still leaps from the grooves of countless mid to late sixties Motown recordings (listen, for instance, to the way in which he transforms the simple two-chord riff of Stevie Wonder’s Uptight), and almost half of Dr Licks’ book is devoted to a scholarly analysis of his style. This includes 49 bass line transcriptions which are played on two accompanying tapes by such Jamerson progeny as Marcus Miller, Anthony Jackson and John Patitucci.

If, as Earl Van Dyke says, much of Motown’s material was ‘crap’, it was frequently redeemed by the work of its jazz-loving rhythm sections, and in particular by James Jamerson. And what he took from jazz he returned, revitalised, to the mainstream. There is hardly a electric bassist today who is free of a debt to him.

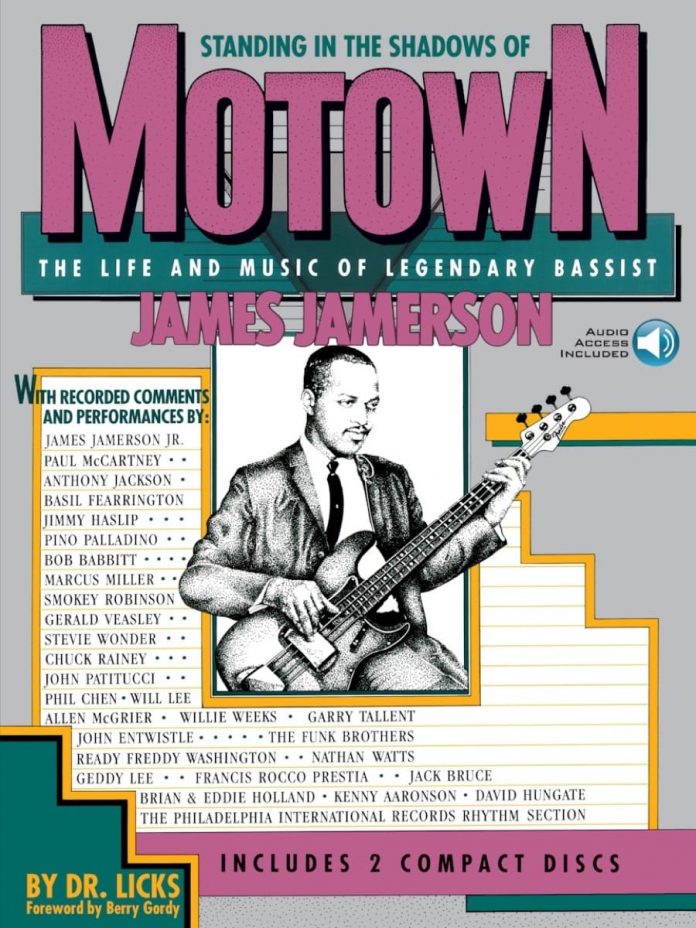

The Life And Music Of Legendary Bassist James Jamerson, by Dr Licks. Dr Licks Publications, pb, 191pp and two cassette tapes, £19.95. ISBN 0-88188-852-4. UK distribution by IMP, Woodford Green.