If there is one way in which jazz musicians prove to be superior to critics as human beings it is in the fact that they rarely criticize one another. Frank Kofsky has here produced a book to help prove the point. It is full of highly personal and often irrelevant attacks on his fellow American critics and this weakens the excellent case he has to put. In many ways it covers ground already charted by LeRoi Jones’ ‘Blues People’ but tends to be prosaic where Jones is passionate.

His worst fault is that he deliberately ignores the truth in an attempt to see the avant-garde as a music that has grown with the black communities. He claims that lack of support for the music is due to factors such as discrimination in clubs, price levels that exclude the poor strata of American society and the artlessness of record companies. Nobody would deny the almost exclusive role played by the Negro in jazz evolution, nor the existence of the factors listed above. The fact remains that Free Jazz has been played in coffee houses and garret clubs with admission free. Yet all save a handful of the young Negros would prefer to go to the discotheque next door to listen to R&B and Tamla Motown sounds.

I also suspect that Kofsky’s knowledge of earlier jazz, forms is sketchy. For him to support the theory that Bix Beiderbecke had little influence shows a lack of perception. His strange definition of atonality also suggests a lack of familiarity with Schoenberg and throughout there is a feeling that he knows jazz only since Charlie Parker.

His worst crime is to try to rewrite jazz history around John Coltrane. He attacks Martin Williams for what has always seemed to me an accurate assessment of the changing face of jazz. He also claims melodists (which Coltrane never was) such as Albert Ayler and Byron Allen as followers of Trane rather than of Ornette Coleman. This undervalues Coleman and, I suspect, tends to set rational observers against the brilliant and influential Coltrane. The tenor man, along with Rollins, whom Kofsky barely acknowledges, played a vital role in the re-directing of jazz. It was Coleman and Taylor who gave the lead in Free Jazz and it is significant that Coltrane’s greatness in the late fifties was matched with a certain mediocrity when he moved into an alien style in the sixties.

This is probably the most vitriolic review I have ever written, but Kofsky is the kind of racialist we can do without. If he ever gets to see this piece, I am sure that he will take my criticism as fascist extremism. The fact is that I hate the entrepreneurs and spongers of the jazz world as much as he does. I champion his right to accuse reactionaries of setting the jazz world at each other’s throats. What I regret is his own self righteousness and the way in which he attempts to put words in Coltrane’s mouth. I am delighted that Trane refused to be led.

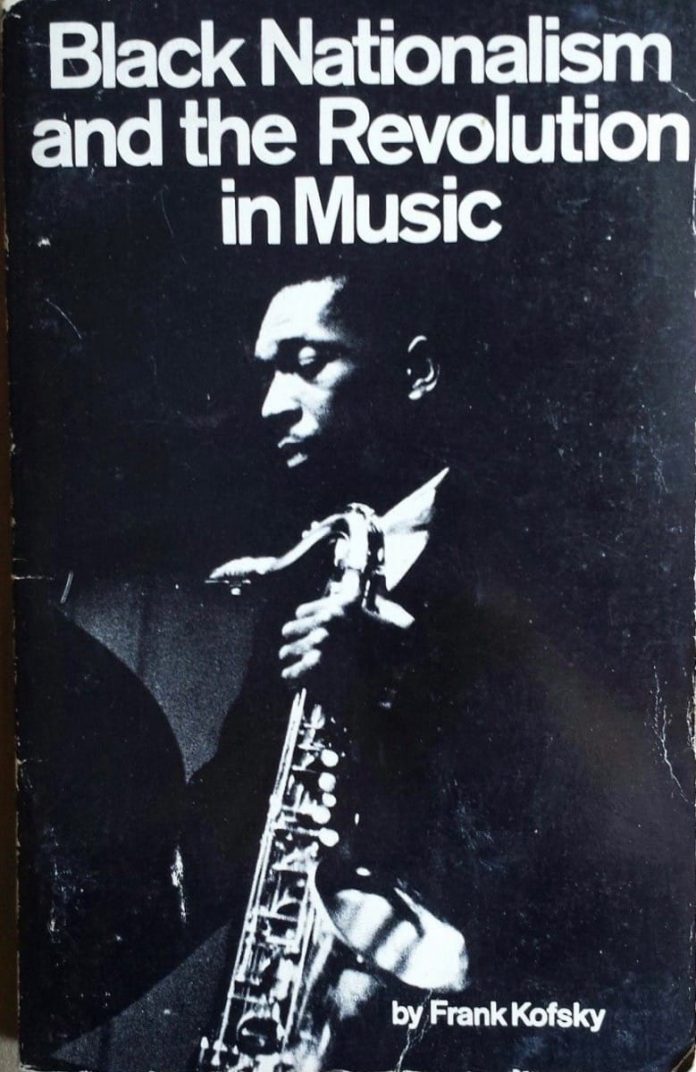

Black Nationalism And The Revolution In Music by Frank Kofsky. Path Finder Press, New York; £3.30 hard; £1.15 paperback. Distributed in Britain by Leder Books, 28 Poland Street, London W1V 3DB.