At 4 p.m. on a quiet Friday afternoon this fall, a group gathered at the Olmstead Recording Studio to record Jimmy Giuffre’s new trio. Besides the leader and his clarinet, there was pianist Paul Bley, a decidedly inner-directed man whose heavy sandals clacked noisily on the steel ladder connecting the studio and the control booth. (“Olmstead, get that sound on the record!” a visitor suggested.) And there was bassist Steve Swallow, barely dry behind the ears professionally – but it is said those young ears are already among the fastest in jazz.

‘I like the pastoral – the country. I like peaceful moods.’ But then he began listening to Thelonious Monk. ‘I heard an element in his music – a way of stating things with conviction that was clear and sure’

Fast ears are what a player needs in Giuffre’s music, for it is often almost totally improvised, except for a memorized statement of the theme. The players ad lib their melodies, sometimes without reference to chorus lengths, chord patterns or any other pre-set structures. The soloist is free to shift his tempo or his key as he wishes, and the others must follow him. They do, immediately. In fact, they seem to anticipate each other even in the most unexpected turns.

The Giuffre trio had just ended a week at Trudi Heller’s Downtown Versailles club in New York. Giuffre felt that after such nightly experience at improvising they were ready to record, and he asked Verve’s artist and repertory man Creed Taylor to set up a session.

“It’s like an instrument, this room,” said Giuffre, warming up his clarinet. He had chosen Olmstead’s studio himself; Verve, like several other companies, does not maintain its own recording facilities but leases them for individual sessions. Giuffre had asked Taylor for this particular one, which tops a ten-story building on 40th street in mid-town Manhattan. A high-ceilinged room painted in pale blue, it displays several irrelevantly ornate Ionic columns on one wall. “It’s half of the old penthouse living room,” says proprietor Dick Olmstead. “It belonged to William Randolph Hearst.”

Olmstead’s is also probably the world’s only split-level recording studio; the glass-enclosed control booth is set about 20 feet above the studio floor, at one end of the room. It houses the engineer’s panel, and will accommodate several visitors.

Olmstead wandered around the studio arranging his microphones. Giuffre cocked his ears for an echo after one of his clarinet phrases. “Yes, this room is an instrument. Listen.” Swallow plucked a note on his bass and attended the reverberations.

Olmstead climbed up to the booth and slid over behind his complex board. Creed Taylor was at his elbow. Below, on the studio floor, Olmstead had placed one mike close in on Bley’s piano, while Giuffre and Swallow were sharing another.

Taylor was there to represent the record company and help Giuffre. He was discreetly quiet, knowing it was best to let Giuffre run the date himself. Unofficially present were Giuffre’s wife of only a few weeks, Juanita; young Perry Robinson, a former clarinet pupil of Giuffre’s; a photographer, who at first respectfully declined to enter the studio while the tape was rolling; and three friends of the Giuffres who dropped in.

“The name of this piece is Whirr,” said Giuffre. “Spell that,” Olmstead said over the speaker, as he bent over his log.

Giuffre pretended to be puzzled. “Well, I will.” He looked at the ceiling. In the booth his wife began to laugh. “W-h-i-r-r-r-r-r . . . ,” he trailed off.

“Blues in B flat,” cracked Swallow, naming the most basic jazz form.

They began fast. Giuffre was playing high and fingering rapidly. “He’ll show those critics!” someone whispered to Mrs. Giuffre. (Because in his early days Giuffre seldom played high notes, a French critic had quipped that Giuffre’s pupils needed a second instructor for the upper register.) At one point Bley hit the bass strings inside the piano with the heel of his hand to get an abrupt sound. And Giuffre got a brief effect like rushing wind by blowing across one of the stops of his clarinet.

“I think that’s it.” said Giuffre at the end of the piece.

Giuffre’s music has obviously come a long way in the past few years. Most people who know him probably first heard of him when he wrote the highly successful piece Four Brothers for the 1949 Woody Herman band. This was the “cool” Herman Herd, and the brothers were a shifting foursome of saxophonists: combinations of Stan Getz, Herbie Stewart, Zoot Sims, Al Cohn, Serge Chaloff and Giuffre. A second wave of fame came in 1957, when he formed the original Giuffre “3” of The Train and the River, Swamp People, and similar impressionistic pieces. Although his music was then gaining him considerable prestige and respect (he had begun winning fan magazine polls on clarinet), Giuffre gradually became dissatisfied with the restrictions his style placed on the players.

“I like the pastoral – the country,” he has said of these times. “I like peaceful moods.” But about then he began listening to Thelonious Monk. “I heard an element in his music – a way of stating things with conviction that was clear and sure. And he played without any restraint – he played it immediately, right in front of you. I also noticed it in Sonny Rollins’ music, this same kind of statement. I got interested in this and started to work on it … I discovered a lot of things … I was holding back a lot of things … I was afraid of hitting certain notes … I worked – and finally got up enough nerve to throw the rock off the cliff and just play anything I wanted to play when I wanted to play it. It was a revelation.”

In all, Giuffre spent more than a year pursuing the idioms of Thelonious Monk and Sonny Rollins. The result was the new Giuffre style that his current trio plays, but to anyone who has followed his career it also seemed like a revelation. This music incorporates the impressionistic moodiness, the textures, and the compositional refinements of the earlier Giuffre “3”. But it also has a new freedom and immediacy. Now, Giuffre the studied composer and Giuffre the player who wants to make strong, spontaneous and uncompromising statements are closer together than ever.

Down in the studio, the trio was ready for the next take. “This is called Afternoon. It feels like a lazy afternoon,” Giuffre explained, half to suggest a mood to the players. “I’ll spell it for you,” he said, smiling up toward Olmstead and Taylor, “A-f-t . . .”

“All right!” Olmstead smiled.

They began with no setting of tempo. Bley was soon answering Giuffre’s improvised phrases in a spontaneous, far-out counterpoint. Swallow looked as if he might drop his bass, he was so acutely involved in the music.

After the number, the trio climbed up to the recording booth for the playback of Afternoon. Giuffre squinted as he listened.

“Let’s try that one again,” said Giuffre, as Olmstead shut off the tape. “For me – you guys were fine.”

Bley protested: “I thought you sounded good.” Giuffre quickly affected a comic pompousness: “I always sound good, but I can do better.”

They clambered down to the studio again. Bley clacked down the steel stairs as Giuffre, behind him, suggested “Let’s leave the chord progression out of this one on the solos. I like the piece but I get tired of that progression. Let’s just play.”

But Giuffre was persuaded that he had played well, and they decided to return to Afternoon later if they felt like it.

They were now about to record Flight. And again they began without a tempo signal; Giuffre merely quietly said “Okay, downbeat,” as the tape began to roll.

There was a goof in the brief written introduction. “How much after you do I come in?” Bley asked.

“Two and a half beats,” said Giuffre. They tried again, twice. Bley interrupted himself on the second. “If I count it, I seem to come in earlier.”

“Oh, I forgot. You come in a beat and a half before me.”

Above, Mrs. Giuffre looked at her husband and laughed quietly; she was around when the pieces were first written.

They started to play. Bley suddenly went into a medium tempo, an easy, rocking jazz groove, and Swallow, too, was on it immediately. Toward the end, Bley surreptitiously reached inside the piano again. The finish of the piece was a long note which Giuffre held softly over the piano’s sustained reverberations.

During the playback, Giuffre asked Olmstead “Dick, can we hear that piece again, on monaural?”

“I don’t know why you want it in stereo at all,” someone remarked. “I mean with the unity you guys have.”

“It still sounds better in stereo to me,” said Bley.

“Sure, you have a whole mike to yourself,” said a visiting musician friend.

The second playback began. Swallow softly clapped his hands to the music and looked at Bley, smiling. At the end of the take, Giuffre’s voice was heard. “I’ll spell it for you, W-h-i-r-r-r . . .”

Some of the pieces seemed to have little of the quality of jazz in the conventional sense. The trio’s work does suggest contemporary chamber music, but only able jazz musicians deeply committed to spontaneity could improvise this way

Some of the pieces seemed to have little of the quality of jazz in the conventional sense. The trio’s work does suggest contemporary chamber music, but only able jazz musicians deeply committed to spontaneity could improvise this way. And only musicians committed to an individual exploration of their instruments and of the personal sounds they can make with them could play this way. No classicists would qualify.

“Everything seems to be going so well,” Swallow was telling Juanita. “I can’t believe it. It must really be going badly. I feel like when I was in school, if I finished a test and handed it in before anybody else.”

Over in a corner Giuffre was earnestly chatting with a new arrival: “At first I didn’t know whether we could get along with piano in place of guitar, but Paul is fine.”

“Are you kidding? You got this Swallow playing guitar parts on his bass!”

“Hey Paul,” said Giuffre, turning to the door, “did you hear a string that’s out of tune on the piano there toward the end?”

“On that piece?” Bley laughed. “Who could know? No, it was muted. I had my hand on it.”

“Well,” said Giuffre, as they went downstairs to the studio, “the next thing I’d like to do is record with this group and an orchestra.” Bley nodded enthusiastically.

Swallow’s voice was picked up from below on the open mikes. “So few notes on that last one. Sometimes with this group I sound like something from the twenties.” They ran through the theme of a piece called Ictus written by Bley’s wife, Carla. The trio had tried to include it on a previous LP but gave up after 18 unsuccessful attempts to get a good version on tape.

“This time it’s going on in one take,” someone whispered to Creed Taylor. He was right.

Swallow watched intently as Giuffre invented his coda, so he would know when to come back in for a last bass phrase. Giuffre unexpectedly pulled his last note out of the air at the end of an abruptly asymmetrical phrase, and Swallow was right on it. Bley concluded with something of his own. No sooner had Olmstead shut off the tape than everybody broke into laughter at the humorous appropriateness of it.

The playback got immediate approval. “Now I think this next one should he very loose,” Giuffre said, throwing his arms in all directions. “You know – very nondirectional. This is called The Gamut,” he announced to Olmstead.

During his solo, Bley began to hum his melody as he ad libbed. Neither Olmstead nor Taylor objected. They both agree with Giuffre that it’s part of the music as the trio makes it.

Again, Giuffre listened to the playback with his eyes half shut. This time Swallow’s eyes were on him, as they had been while they were playing. Suddenly everyone realized that all three of them at one point had spontaneously fallen into playing a little traditional jazz phrase. “Yeah that’s a good figure there,” said Bley quietly. Later he turned to Swallow. “You see, when we set him up, that Giuffre really plays a good solo.” They laughed and then listened carefully to the way Bley had finished the piece with an unusual sound from the piano.

“We ought to end with that,” said Giuffre.

Creed: “You mean end the record!”

“Yes,” said Giuffre and Swallow in unison.

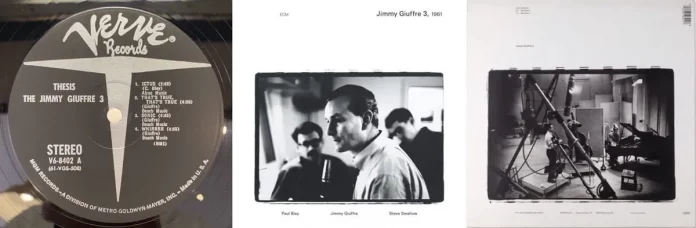

Giuffre looked at his watch. “Hey, we’ve still got the studio for half an hour, haven’t we, Dick? Let’s hear it all back again. We’re all finished. We’ll call this album Thesis.”

“Finished now”!”

“Sure. After all, we only did one piece twice; there isn’t much choice to make, and there’s no editing. I’ll spell it for you. F-i-n-i-s-h-e-d.”

(This article originally appeared in FM/Stereo)

Related discography (courtesy jazzdisco.org)

The Jimmy Giuffre 3

Jimmy Giuffre, clarinet; Paul Bley, piano; Steve Swallow, bass.

Olmsted Sound Studios, NYC, March 3, 1961

23493-3 Used To Be Verve V/V6-8397

23494-3 Emphasis Verve V/V6-8397; ECM (G) ECM 1438/39

23495-1 Brief Hesitation –

23496-1 Venture –

23497-5 Trudgin’ –

23498-6 Jesus Maria –

23499-3 In The Mornings Out There –

23500-8 Cry, Want –

23501-4 Scootin’ About –

Afternoon ECM (G) ECM 1438/39

* Verve V/V6-8397 The Jimmy Giuffre 3 – Fusion

* ECM (G) ECM 1438/39, ECM 1438/39 (CD) Jimmy Giuffre 3, 1961

The Jimmy Giuffre 3

same personnel.

Olmsted Sound Studios, NYC, August 4, 1961

61VK267 That’s True, That’s True Verve V/V6-8402; ECM (G) ECM 1438/39

61VK268 Ictus Verve V/V6-8402, VE-2-2514; ECM (G) ECM 1438/39, :rarum 8015

61VK269 Asphalt (as The Gamut) Verve V/V6-8402; ECM (G) ECM 1438/39

61VK270 Sonic –

61VK271 Carla Verve V/V6-8402, VE-2-2514; ECM (G) ECM 1438/39

61VK272 Whirrrr –

61VK273 Goodbye Verve V/V6-8402; ECM (G) ECM 1438/39

61VK274 Flight –

Me Too ECM (G) ECM 1438/39

Temporarily –

Herb And Ictus –

* Verve V/V6-8402 The Jimmy Giuffre 3 – Thesis

* ECM (G) ECM 1438/39, ECM 1438/39 (CD) Jimmy Giuffre 3, 1961

* Verve VE-2-2514 Various Artists – Masters Of The Modern Piano (1955-1966)

* ECM (G) :rarum 8015 Carla Bley – Selected Recordings