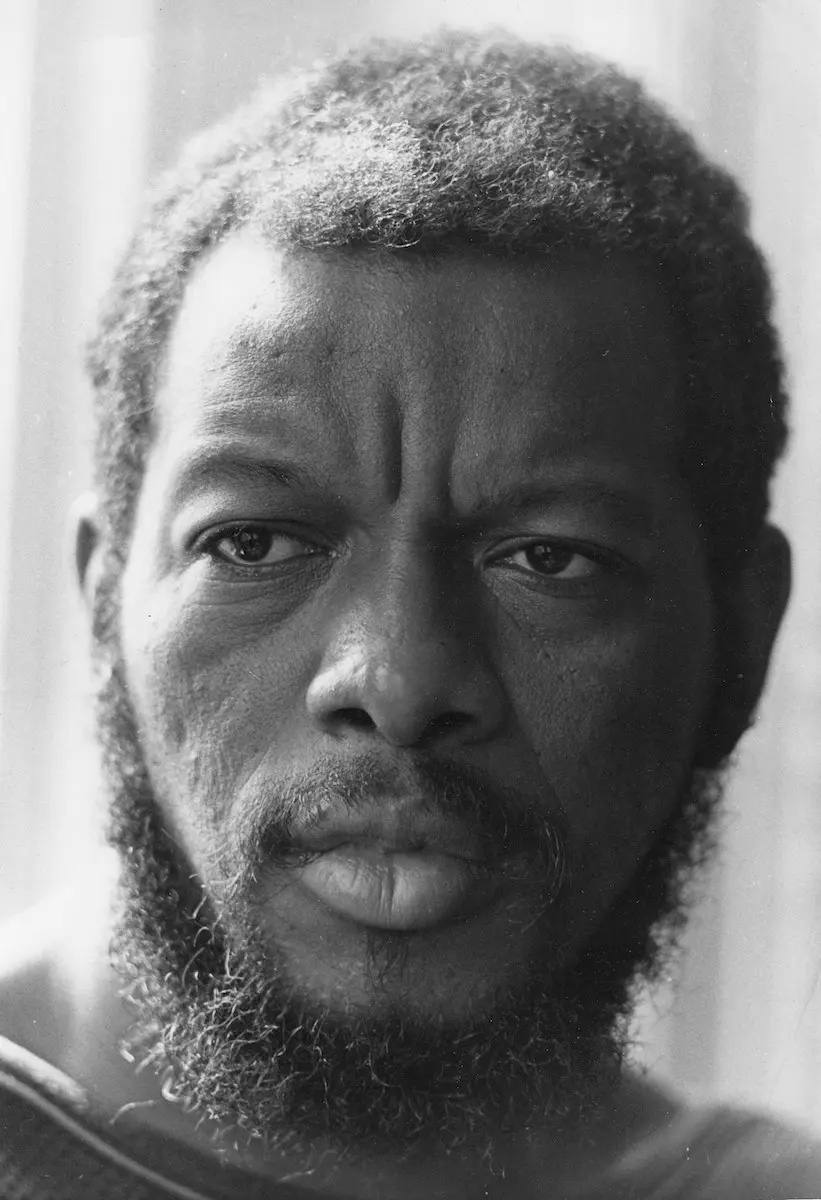

In contravention of his own musician’s union ruling, Ornette Coleman appeared in a concert at Fairfield Hall, Croydon on August 29th. It was presented by the Live New Departures unit, and marked not only his sole English appearance but also his first live performance in Europe.

The result was some of the greatest jazz ever presented in this country. Coleman, leading his regular trio, of David Izenzon (bass) and Charles Moffett (drums), played seven numbers. All were new to listeners conversant only with his recorded work and they again confirmed that he is among the leading jazz composers. His approach to jazz writing, however, is very different from that of the previous era. The harmonies of his themes do not direct his solos and he makes only oblique references to them. He uses the melody statement as a mere launching pad and then embarks on solos that are made of unrelated, melodic fragments. At times these are succinct and self supporting while at others they constitute an idea that is paraphrased in the following few bars. Since there is no harmonic base, each adaptation resembles the original phrase only in its general design and interior balance.

Fairfield Hall proved to be an ideal place to hear the subtle nuances of his style and the other members of the trio provided a sympathetic and shifting backdrop. Moffett is a left-handed drummer who uses this contingency to very good effect. His top cymbal figures deftly filled the gaps in Coleman’s essentially broken line while his right hand completed the polyrhythmic tattoo with frequent excursions into double time. But his talents are not purely rhythmic and, like his leader, he exhibited a wonderful control of dynamics. He listened with great care to both Izenzon and Coleman, and whether at a whisper or in a thunderous climax, played nothing that was not both apt and exciting.

Izenzon was equally brilliant. His pitching in arco passages was very accurate and his articulation when playing pizzicato almost breathtaking. In view of this, it might seem carping to criticise his contribution to the trio. Nevertheless, I could not help feeling that his preoccupation with intricacy for its own sake did not help the altoist in his more austere and moving moments. At faster tempos Izenzon’s independent, melodic line provided a tension that stimulated Coleman to his most brilliant, chromatic freedom. On the slows this was not the case and the bassist’s use of the available harmonic licence did not always serve the group’s best interests. Like the gifted Scott La Faro, Izenzon occasionally paraded his dexterity at the expense of his vital contrapuntal responsibilities. Coleman appeared oblivious to this but the listener was conscious of a breakdown in the group integration.

The trio’s first number, introduced by Izenzon’s sonorous arco bass, was Sadness. This appropriately titled piece drew a haunting solo from Coleman and an enthusiastic response from the audience. Next came The Clergyman’s Dream, which recalled his recorded Lorraine (1959) in structure if not melodic content. It opened with adroitly handled tempo changes before resolving into a jaunty medium tempo. The trio showed fine integration here and Coleman responded with a solo full of discovery.

The moment that everyone had eagerly awaited, arrived when Coleman reached for his violin for Falling Stars. No existing standards can be applied to his use of this instrument and, if a parallel does exist, it can only be in the field holler. Coleman bows at incredible speed and makes no attempt at melodic investigation. He leaves all continuity to bass and drums while he provides an arhythmic layer of sound above them. As such, it is hardly satisfying and, in view of Coleman’s great invention, must be viewed as a dissipation of his talent. His trumpet also made its only appearance on this number and, although he used it in a more orthodox manner, his technical limitations again proved a barrier to real continuity and relaxation.

After the intermission, Coleman concentrated on alto and played with authority. As an aid to his fertile imagination he shaded his solos with endless tonal inflections. As always he transcended the rules of European harmony and gave his horn a veraciously vocalised sound. His tone is beautiful when heard live and his coarse-grained groans have a singing quality, not always apparent on record. His sense of humour is never far below the surface and in the opening of Silence he squashed a barracker with the ease of a politician. During one of its many tacit breaks he was urged by this ‘humorist’ to play Cherokee. He seemed quite unmoved but, shortly after, concluded a blues-drenched phrase with the required quotation. This was perhaps typical of the whole performance. In the process of creating magnificent music, the trio seemed almost casual. Coleman made no announcements but said so much with his horn that comment was unnecessary. It was perhaps fitting that the group’s final number before the encore was the highlight of a wonderful evening. It was an untitled ballad and it found Coleman at his finest. His slow and passionate solo was very moving and, while his method remains near to that of his first recordings in 1958, one can detect a more finely developed sense of timing.

I have long thought Ornette Coleman to be one of the greatest of all jazz musicians and, during this all too brief evening, he did much to confirm my view. The supporting cast was made up of poets, whose often pleasing work I am unqualified to judge, and a virtuoso ensemble that gave a perfect reading to Coleman’s original Forms and Sounds for Wind Quintet. In addition there were several numbers by the Mike Taylor Quartet – a group of young British musicians working in the Coltrane manner. Although a good musician, soprano saxophonist Dave Tomlin was rather too formal in his approach to this style of jazz and there were times when the leader’s piano was a little static. On the whole, however, they played in an imaginative way and showed the kind of potential that bodes well for the future of British jazz. It is doubtful whether the well-known musicians originally booked would have made a greater impression in the face of Ornette Coleman’s inspired playing.