Before I’d ever heard this album it seemed familiar because I had read so much about it, including classical composer, conductor and critic Gunther Schuller’s scholarly analysis of Blue Seven. The album, and that track in particular, seemed to be universally considered a masterpiece. I got the 1964 Stateside LP one Christmas and was well on the way to wearing it out by New Year. According to discogs.com it has been issued in 157 versions, legit or otherwise.

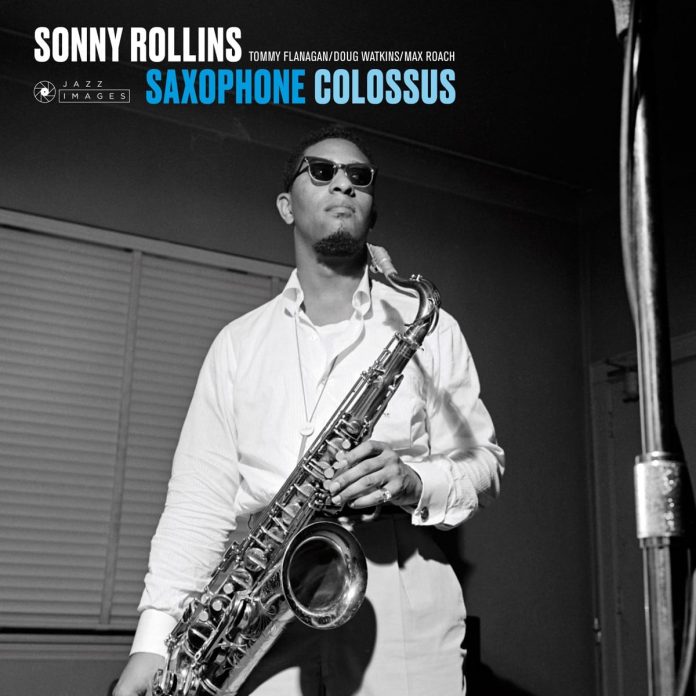

Saxophone Colossus was recorded just a few weeks before Rollins’s 28th birthday. The title might have seemed presumptuous, even though Rollins had already built up an impressive catalogue with Prestige (Work Time, Sonny Rollins Plus Four and Tenor Madness) but someone evidently had the perspicacity to recognise that this session was something extra special. Rollins was not a prolific composer but three of the tunes here are his, the other two being a beguiling standard and a Kurt Weill tune, better known as Mack The Knife, from Brecht and Weill’s The Threepenny Opera.

Rollins’s solo on Blue Seven is one of those rare improvisations that smacks of inevitability and makes you think there are no reasonable alternatives to the choices the soloist makes. Its reputation has somewhat obscured the fact that the other tracks are excellent too. The calypso-influenced St. Thomas is an exuberant tribute to his parents’ Caribbean heritage. You Don’t Know shows off his lower and middle-register tone nicely in the theme statement before he launches into an improvisation that has a strong bebop flavour. Strode Rode is a bustling staccato nod to his spell in Chicago a couple of years earlier. I’ve always rated Moritat as highly, if not higher, than Blue Seven (it demonstrates Rollins’s acute melodic sense and wit especially well) but who am I to question Schuller? The distinguished rhythm section is excellent throughout and Flanagan is on especially good form.

The original LP included only the first five tracks listed below. (I say “only” but those 39 minutes 54 seconds contained enough superb music to keep you engrossed for as long as you like.) The seven bonus tracks straddle an important period in Rollins’s development, from the 1953 performance with the Modern Jazz Quartet when he had yet to demonstrate what an exceptional talent he was, to the lovely 1962 piece recorded after he had returned from a two-year sabbatical during which he tried to work through his dissatisfaction with his own direction. Nonetheless, these selections act as a kind of sampler rather than a coherent outline of the evolution of Rollins’s approach. That said, they are all worth having in their own right.

Discography

(1) St. Thomas; You Don’t Know What Love Is; Strode Rode; Moritat; Blue Seven; (2) When Your Lover Has Gone; Paul’s Pal; My Reverie; The Most Beautiful Girl In The World; (3) In A Sentimental Mood; (4) Manhattan; (5) God Bless The Child (78.08)

Rollins (ts) with:

(1) Tommy Flanagan (p); Doug Watkins (b); Max Roach (d). Hackensack, New Jersey, 22 June 1956.

(2) Red Garland (p); Paul Chambers (b); Philly Joe Jones (d). Hackensack 24 May 1956.

(3) Milt Jackson (vib); John Lewis (p); Percy Heath (b); Kenny Clarke (d). NYC, 7 October 1953.

(4) Henry Grimes (b); Specs Wright (d), NYC, 10 July 1958.

(5) Jim Hall (g); Bob Cranshaw (b); Harry T. Saunders (d). NYC, 30 January 1962.

Jazz Images 38121