As of 2025, Sonny Simmons – saxophonist, player of the English horn and composer – embodies a strand of the jazz tradition that’s been kind of overtaken by cultural change and changes in cultural attitudes.

In common with a great many musicians of his era Simmons got a foothold in the music business through working the rhythm and blues scene with the likes of Lowell Fulson, Amos Milburn and T-Bone Walker, the last of whom he worked with for approximately one week. By his own admission he learned more about showmanship than musicianship in that period, but as his career progressed (and indeed how that career might be considered stalled when he was reduced to playing on the streets from 1980 until 1994) it was his dedication to “the music” that sustained him in face of the often negative hand that life dealt.

Although in the last two decades of his life Simmons enjoyed a revival, embarking on European tours, leading new ensembles and recording a series of albums before his death in 2021 at the age of 87, that negative hand is the underlying context of this book. Simmons is to be admired for the way in which he sweetens nothing and is frank about his use of drugs, largely and by no means uniquely as a means for escaping a harsh reality that most contemporary jazz musicians, formally schooled and blithely marketed as they often are, have no experience of.

Simmons’ first-hand experience of the likes of Eric Dolphy (with whom he recorded in the early 1960s) and John Coltrane, and his advocacy of Jewel Sterling, a tenor sax player whom Simmons claims was playing advanced harmonics in the mature Coltrane manner back in the 1950s, serve, however, to place him far closer to “the greats”.

While his own work tipped the hat in the direction of such figures, his individuality across a discography spanning decades remains apparent. What this book makes equally apparent is how the playing and recording sides of the business, governed as they sometimes can be by individuals with less than ethical motives, serve to forge a personality. As an author, Simmons maintains his personality as a musician, complete with the integrity that implies.

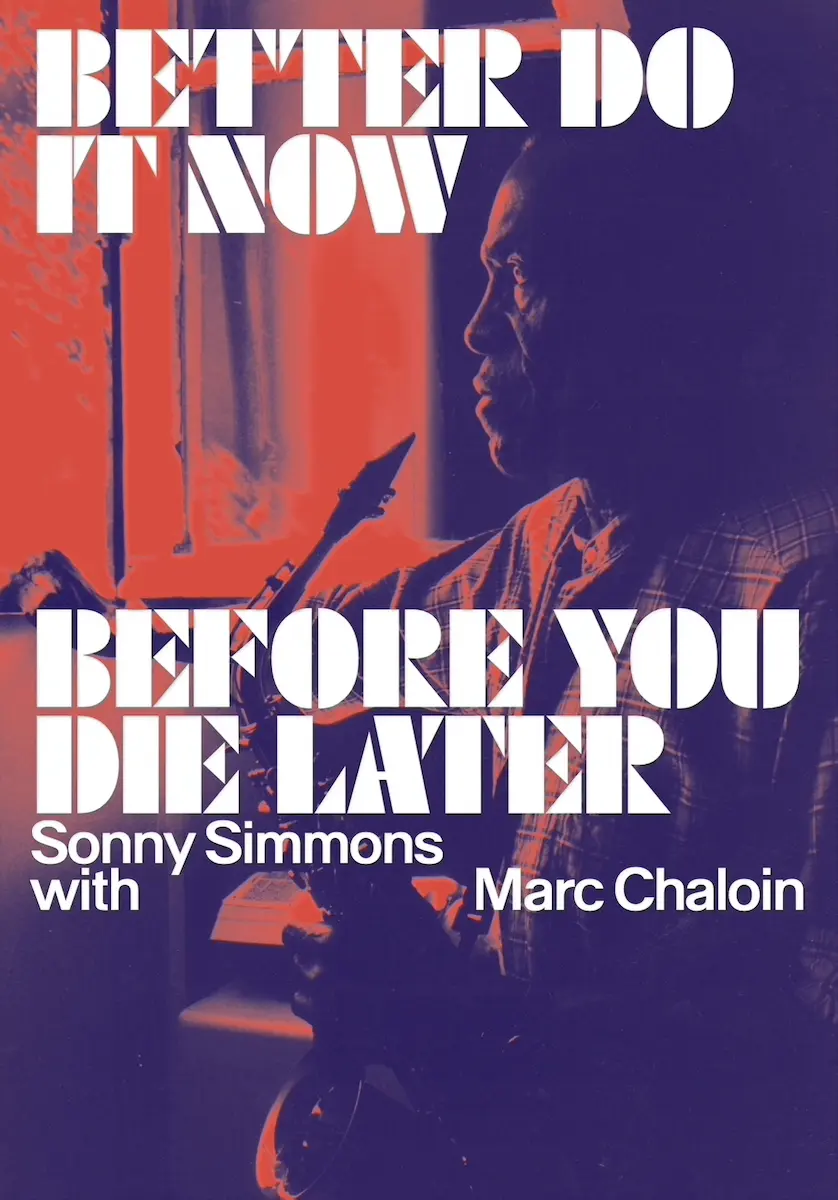

Better Do It Now, Before You Die Later, by Sonny Simmons with Marc Chaloin. Blank Forms Editions, 531pp, hb, £37.00. ISBN 978-1-953691-21-7

Press release: Though his years in the New York free-jazz scene of the sixties cemented his reputation as “one of the most forceful and convincing composers and soloists in his field,” saxophonist Sonny Simmons (1933–2021) was nearly forgotten by the eighties, which found him broke, heavily dependent on drugs and alcohol, and newly separated from his wife and kids. “I played on the streets from 1980 to 1994, 365 days a year,” Simmons tells jazz historian and biographer Marc Chaloin in Better Do It Now Before You Die Later. “I would go to North Beach, and I’d sleep in the park. The word got around town that Sonny is a junkie, really strung out.”

The resurrection of Simmons’s career – upon the release of his critically acclaimed Ancient Ritual (Qwest Records) in 1994 – has become a modern legend of the genre. In the last two decades of his musical career, Simmons broke through to a new echelon of recognition, embarking on successful European tours, leading new ensembles, and recording a series of twenty-first-century albums that inducted him, by his death at the age of eighty-seven, into the pantheon with the great innovators and masters of the music. But to this day he remains an undersung figure. Here, in the first-ever book dedicated to his life, Simmons recounts his childhood in the back- woods of Louisiana, his adolescence in the burgeoning Bay Area jazz scene and his star-studded life in New York playing alongside the greats: Sonny Rollins, Eric Dolphy, and John Coltrane. His testimonies from each time and place add up to a cultural history of the late twentieth century: Simmons saw Billie Holiday and Thelonious Monk at the Black Hawk, lived through the Watts riots, stashed guns for the Blank Panther Party, brushed shoulders with Jefferson Airplane and Jimi Hendrix, and toured Europe amid the multiculturalist boom of the nineties. But it’s his keen memory for the underdogs and up-and-comers that distinguishes Simmons’s voice. He talks plenty of shit on his rivals – Pharoah Sanders and John Handy were, in Simmons’s words, “hip … great players, but I was the cat who was moving.” Meanwhile, Miles Davis was “arrogant and blasé and talking shit,” and Prince Lasha “got scandalous with his lover-man shit.” But Simmons reserves his most ferocious loyalty for names elsewhere unremembered, like the altoist Alfred Franklin, the mononymous Hop, or the Wild Man, Stanley Willis. Of the “brilliant motherfucker” and tenorist Jewel Sterling, as of many others, Simmons declares, “I don’t want to forget that brother. I want to resurrect him too.”

Whether he’s writing about his many love affairs; his turbulent romantic and creative partnership with the accomplished jazz trumpeter Barbara Donald; the pain of seeing his friends and heroes laid low by addiction; or the racism he endured in evolving forms across decades and states, Simmons brings the ferocity of style that animated his music to every sentence. And underneath it all remains the electric charge of his artistic passion. “I think all I needed during them terrible periods in darkness and despair was to play,” he writes, of his hardest years in San Francisco. “To be able to express the music in me was like a cleansing ritual.” Like Charles Mingus’s Beneath the Underdog and Art Pepper’s Straight Life, Simmons’s Better Do It Now Before You Die Later delivers an unfiltered, firsthand account of life in the bebop business in all its brilliance and brutality, capturing the devastating lows of addiction, poverty, and obscurity and the ecstatic highs of a life dedicated to The Music.