Seeing the Count Basie Orchestra live was one of the great thrills early in my lifelong obsession with jazz. I did not realise it at the time, but the experience also allowed me to glimpse the remnants of a paradigm shift in American popular culture. Though I get Merle Haggard when he sings “I think we’re living in those good old days,” the golden age Basie represented had long passed by 1978, the year I met the Count.

The concert took place in September, the month of my 24th birthday, at Seattle’s elegant Olympic Hotel ballroom. Tickets cost 15 bucks, a significant chunk of change for me back then. Guess I had no girlfriend at the time, and my best jazz buddy in town baulked when I told him the price of admission, so I went to hear the Count all by myself. My hands clutched a two-record set of Count’s classic late-30s orchestra that I hoped to have him sign.

I appeared to be the youngest person there as I lurked near the back of the room, behind tables populated by mature couples, all waiting for the music to start. Soon as it did, the couples invaded the dance floor, eagerly, as though starved for a chance to show off their moves.

Starved? But of course they were. It occurred to me just recently that they were reliving the glamour and passion of their youth in the afterglow of a dance-crazy America. Though by the time these happy hoofers had come of age in the 40s, vocalists like Frank Sinatra and Peggy Lee had begun to eclipse big-band leaders like Goodman and Shaw as the idols of musical entertainment, many of the bands had traction left and dancing remained popular.

Two or three decades earlier – when these undulating couples had been in their late teens or early 20s – Americans danced. Perhaps some of them had been habitués of Seattle’s legendary Trianon Ballroom in the late 30s to early 40s when Gaylord Jones led the house orchestra there. Quoted in Paul de Barros’s book on the roots of jazz in Seattle, Gay recalled the Trianon jitterbuggers: “Some of them were really spectacular, throwing the gal around and under their leg and up in the air. There were some of those tunes we’d play where the whole doggone place would – I’d be worried about the floor giving way.”

De Barros describes what they’d have seen had they paid their dollar admission and entered the Trianon: the ballroom “covered half a block at Third Avenue and Wall Street. It was the biggest ballroom in the Northwest. The dance floor, made of springy white maple, spanned 30 by 135 feet, accommodated 5,000 dancers, and was fitted all around with ducts that sucked the stale air away. Around the dance floor were 150 three-person settees; upstairs, the loges seated 300 to 400 people, and there were 16 arched, open-air balconies where lovers could retreat.”

Nowadays, we go to a band concert, sit in a chair, listen and applaud dutifully. In the swing era, people went to a band concert intending to dance. Indeed, when a band came to town, it was advertised as a dance date, not a concert

If not the Trianon, maybe those couples dancing to Basie at the Olympic had tested the floorboards in one of the nearly two dozen other ballrooms or roadhouses that catered to patrons with happy feet from Seattle to Olympia, 60 miles to the south. Seattle, of course, was no different from any other urban area in those days.

De Barros tells us what set the Trianon apart: “At the far end of the room was the prize of the establishment: a silver clamshell hood over the bandstand that projected sound beautifully out over the dancers.”

On this stage, the dancers would have seen a big band of 16 or 17 uniformed musicians arrayed in serried ranks – saxophones sitting in front, behind them the trombones, also seated, and standing in the back, the swashbuckling trumpets – flanked by the rhythm section of piano, bass and guitar, the drummer in back, surrounded by a phalanx of percussion accoutrements. Unless an Ellington, Earl Hines, Claude Thornhill or Basie who sat at the piano, the orchestra leader directed from out front, often holding an instrument. A few led from behind on drums. Sharing the stage with the leader stood the canary, the girl singer, looking glamorous in her floor-length gown as she waited dutifully to chirp her single vocal chorus as one of the band, not the star attraction.

Hundreds of bands, possibly more, prowled the highways and byways, criss-crossing the country in endless tours of one-nighters, or if lucky, landing a residency in a hotel, restaurant or nightclub. They travelled by rail, by band bus, by private cars. Some of the big bands – Basie, Ellington, Lunceford, Dorsey, Goodman, Shaw, Miller – achieved great fame, but many more did not. The name bands travelled coast-to-coast while legions of long-forgotten territory bands kept within a confined area, the Southwest maybe, or the Upper Midwest, or the Northeast. Only jazz historians remember them today.

Even the famous bands did not limit their activity to posh big city clubs or concert venues. One of the great live recordings of the Duke Ellington Orchestra took place on 7 November 1940 in, of all places, Fargo, North Dakota. This was the so-called Blanton-Webster band, considered by many Duke watchers to be his best ever. But Fargo? Mere mention of the place suggests empty spaces, desolation, freezing winters and tough conditions overall. No matter. The bands went everywhere, even the famous ones stopping off in towns far from the jazz centres of New York, Chicago, Kansas City and Los Angeles. Wherever they went, the masses came out and danced. (1)

Nowadays, we go to a band concert, sit in a chair, listen and applaud dutifully. In the swing era, people went to a band concert intending to dance. Indeed, when a band came to town, it was advertised as a dance date, not a concert. Concerts were for Carnegie Hall or the Hollywood Bowl. Everything else was for dancing. Duke at Fargo in 1940 at the Crystal Ballroom was, no surprise, a dance date. And the dancers stopped only when old age or infirmity forced them. As long as they were able, when the Duke or the Count, or whoever else had survived the dismantling of most of the big bands after 1945 came to town, the people went intending to dance. In March of 1958, when the Duke played concerts at the Travis and Mather Air force bases, they were dance dates. And for the happy couples at the Olympic Hotel Ballroom in Seattle that day in 1978, Basie’s appearance was a dance date.

I soon spied my kindred spirits. Clustered around the bandstand, not dancing, not socialising, they were just flat out digging the Count! The guy right up front, leaning onto the stage, even wore a beard and blue jeans

While I enjoyed watching the dancers, their gaiety made me feel a little isolated and alone, wondering if I were the only one without a partner. But I soon spied my kindred spirits. Clustered around the bandstand, not dancing, not socialising, they were just flat out digging the Count! The guy right up front, leaning onto the stage, even wore a beard and blue jeans. All of them beamed, unable to remain indifferent in the glorious presence of jazz royalty, literally standing at the feet of Count Basie and his swinging, roaring, joyous 16-piece orchestra. Without hesitation, bowing to an irrefutable urge, I joined them, my loneliness vanquished by the greatest swing machine ever assembled (a claim I’d make for any version of the Basie band).

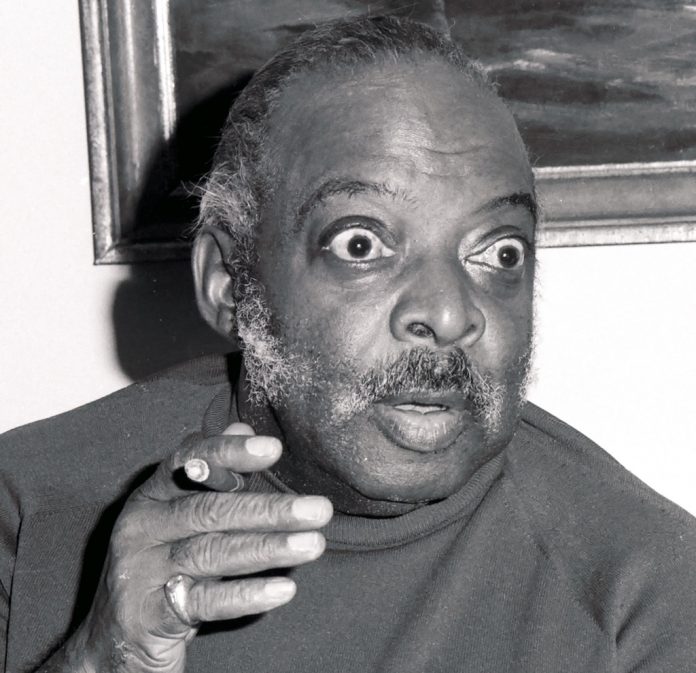

To begin with, there, beaming his mega-watt smile, sat the regal being himself at the piano. A smiling minimalist, “plink . . . plank . . . plink,” more myth than man, Count teased us with that uncanny rhythm born of countless hours cruising the trade winds of jazz, fronting an eternity of one-nighters, flying with the memory of the greats – Buck Clayton, Harry Edison, Herschel Evans, Prez and the fleet, All-American rhythm section rounded out by Walter Page and, sticks in hands suggesting poetry in motion, Papa Jo Jones. Sitting near the Count, legs crossed, calmly strumming his guitar, Freddie Green – the only holdover from these legends of the original Basie Orchestra of the late 30s – displayed all the dignity of an African diplomat.

I don’t remember the names of the sidemen, but each was, to a man, the pith of cool. (Likely this was the Sonny Cohn, Dennis Wilson, Eric Dixon, Danny Turner and Butch Miles edition.) When someone’s turn came for a solo, he casually sauntered down from the risers like a graceful panther, took up position in front, and on the precise beat he was to begin, lifted his horn and blew.

Ballads, barnstormers and blues, it all flashed by in a blaze of Basie glory. After all these years, I no longer remember much of the music they played, though I clearly recall the reverent hush that fell over the room as they slow-baked a crawling tempo on Neil Hefti’s famous Lil’ Darlin’. It was played so slowly it risked collecting dust. The unison phrasing made a sound like one big fat instrument. That memorable performance is the only tune from the show whose name has stayed with me.

I’m glad I got to witness those swinging adults, revisiting their younger days as they danced in the Count’s court. They were lovely. They are also reminders of a time when popular culture was softer of tone, less in your face than in more recent times. It was an era when the popular songs of the day were odes to the moon and stars, or to birds, or to mythical visions of the old South, or to love itself. Many of the songs, no surprise, riff on dancing, from a variety of angles, with titles like Dancing In The Dark, Steppin’ Out, I Won’t Dance, Let’s Face The Music And Dance, Ten Cents A Dance, Posin’, Cheek To Cheek, The Last Dance and, one of my favourites, Irving Berlin’s sweet, wistful exercise in chromatics, Change Partners.

The songs did not take themselves too seriously, even though their creators – and they were pros at writing songs; that’s what they did – were bent on crafting the best possible product they could. Nor did they feel the need to express social significance or suggest deep secrets buried in the lyrics. If they made references to sexuality, the act was implied, not explicit. They existed to delight, not shock, us. Irving Berlin, Jerome Kern, Rodgers and Hart, George and Ira Gershwin, Cole Porter: they were colleagues and also competitors, striving to find novel and creative ways to say “I love you” in 32 bars.These talented and accomplished men – and others like them – blended melody, harmony, words and rhythm, gifting the world the greatest flowering of danceable popular songs ever heard. (2)

Before popular singing became an exercise in melisma, like an Olympian event, vocalists sang in natural, though cultivated, voices

And before popular singing became an exercise in melisma, like an Olympian event, vocalists sang in natural, though cultivated, voices: Sinatra, Holiday, Armstrong, Crosby, Fitzgerald, Vaughan, Doris Day, Dinah Shore, Dinah Washington, Rosemary Clooney, Carmen McRae, Chris Connor, Jo Stafford, Kay Starr, Johnny Hartman, Mel Tormé, Nat Cole, Dick Haymes, Matt Monro, Dino, Billy Eckstine, at least five Helens – Forrest, Humes, Merrill, O’Connell, Ward – and two leading ladies of a less-is-more vocal style, Peggy Lee and Maxine Sullivan. (3) (There are many others.)

Sure, I’m aware that every one of the songs that has become a standard had to vie for attention with possibly dozens that were mediocre, or worse. And of course other musical delights have come and gone since those halcyon days. Fans or scholars of the classic rock bands of the 60s and 70s may well make a case for a golden age of that genre. But if durability is any measure of quality, it is worth noting that the standards still in the repertoires of jazz singers or musicians are approaching their centennials, if they have’’t already got there. But will they still dance to Gershwin, Kern or Porter 100 years from today? That’s for those who come after us to answer.

After the gig, a Basie greeting line had formed, and clutching my precious album, I joined in, a bundle of nerves and anticipation. Holding court in the middle of the ballroom floor sat the Count on his throne, maybe just a room chair – attended by a matronly woman – greeting his subjects. As I waited in line, I noticed several attractive young ladies ahead of me. One by one, they would go up to Basie, throw their arms around him, and plant a big kiss on his cheek. The Count was loving it.

Finally, my turn came and I found myself standing before the Great One. I mumbled something quite possibly unintelligible, shook his extended hand, and holding out the album I had lugged around the entire evening, asked him to sign it. Count took the record, studied it for a bit, and then looked back at me, wide-eyed and expectant, saying “Hey, man, this is the original band . . . look, there’s Lester Young, and Herschel Evans, and . . . where did you get this record?” I made some clumsy response – not finding the best words to explain that it was a recent reissue of his classic band cuts on Decca – all the while thinking “Wow, this is his band, and it’s like the first time he’s seen the record. That’s crazy.”

As I turned to leave, the matronly one smiled and said “Don’t lose that record.” “Oh, I won’t,” I responded like an obedient Methodist choirboy. I still have it all these years later, along with that memory of the Count Basie Orchestra killing Lil’ Darlin’, the couples locked in each others’ arms, lost in the slow dance, the cares that hung around them through the week vanquished. Like Mr. Berlin, they enjoyed nothing half as much as dancing cheek to cheek.

Coda

On 29 March 1984, Count Basie and his 16-piece orchestra were booked to play the historic Mt. Baker Theater in Bellingham, Washington. As a resident of that fair city at the time, I very much looked forward to seeing him again. However, a couple months before the gig, the Count took ill and the show was cancelled. He died on 26 April, nearly a month after the scheduled date.

(1) Certainly all of the big bands would have included a place like Seattle on their itineraries, despite it being tucked up in the Pacific Northwest, relatively far off the beaten track. In my interviews with such old timers as Jack Perciful (Harry James band), Red Kelly (James, Barnett, Herman, etc.) and Buddy Catlett (Basie and Armstrong bands) who hailed from this provincial seat, the name that came up most often was that of Lunceford. This orchestra, it seems, left an impression that would persist for many decades.

(2) Though fewer in number than their male counterparts, let us not overlook the talented women of Tin Pan Alley, foremost among them Dorothy “I Can’t Give You Anything but Love” Fields, Kay “Can’t We Be Friends?” Swift, and Anne “Willow Weep for Me” Ronnell.

(3) Kudos to those who buck trends to carry on this grand vocal tradition: Rebecca Kilgore, Diana Krall, Dawn Lambeth, Diana Panton, Hannah Richardson, Barbara Rosene, to name a few.

Work cited

de Barros, Paul, Jackson Street After Hours: The Roots of Jazz in Seattle, Sasquatch Books, Seattle, 1993.