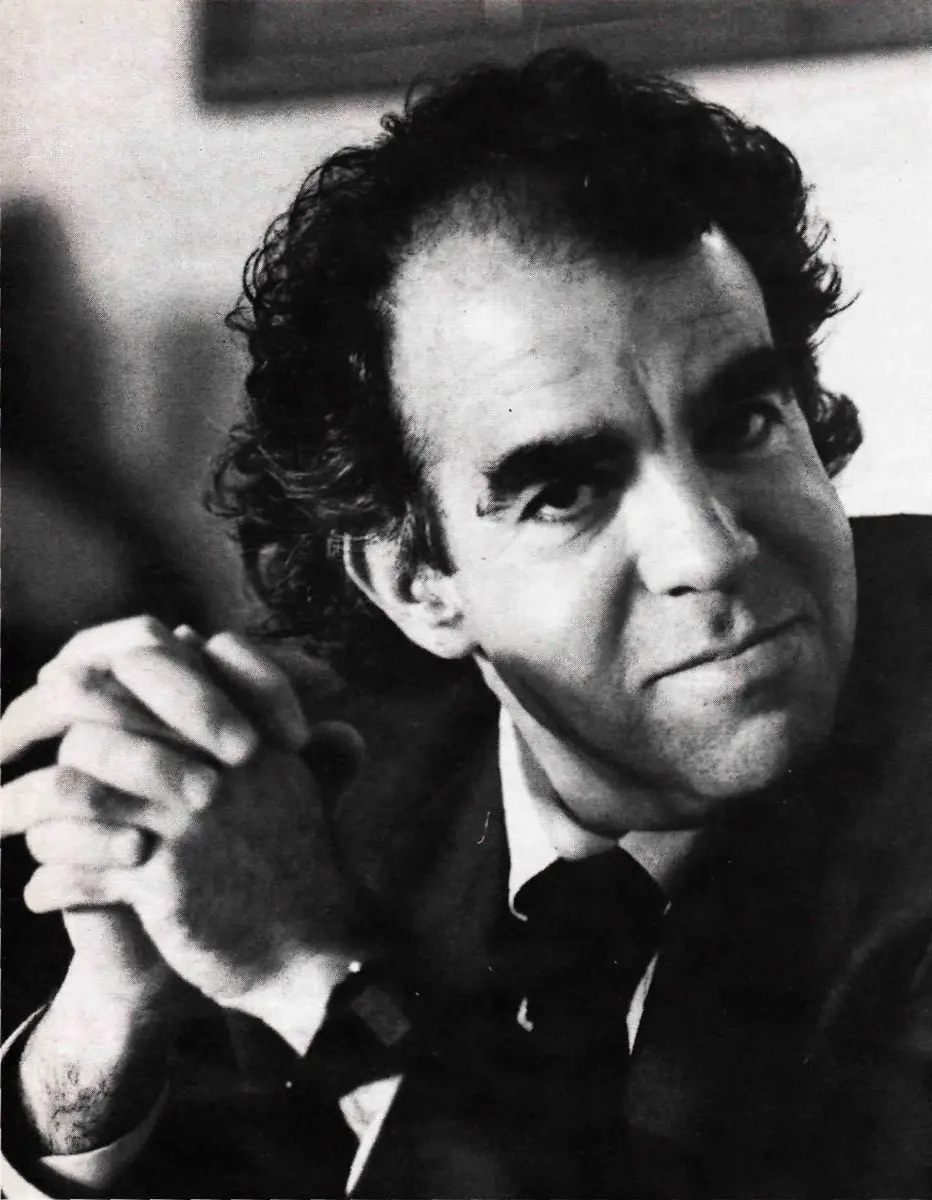

Although he frequently brought his jazz skills to bear in top drawer sessions with Steely Dan and others in the seventies, pianist Don Grolnick didn’t come into international view as a jazz player until his brief period with Steps (later Steps Ahead) in the early eighties. Since then, his dramatic, virtuosic writing has been heard in two outstanding dates for Blue Note, both of which arrive at that often trumpeted but rarely realised thing, a genuinely novel reading of the hard bop tradition. Grolnick spoke to Mark Gilbert during a CMN tour by his octet earlier this year.

I first encountered your playing in Steps Ahead. . .

‘When I was in the band it was just called Steps. That started off with Mike Mainieri; he called us to play at Seventh Avenue South, the club that Mike and Randy Brecker owned, and we just did a gig. If I remember rightly it was the Breckers, Steve Gadd, Eddie Gomez and myself. Then a Japanese label became interested in us and brought us over to Japan and we made two records in one week. We played at the Pit Inn and recorded live there, and we also went into the studio and recorded a different album which came out a year or two later. And then somewhere in there we had to make a name, so somebody picked the name Steps. And eventually it turned out some other band had the name Steps, so they changed it to Steps Ahead. By that time I had already left the group; then Steve Gadd left and Peter Erskine played. Then Eddie went, and so on. And now Steps Ahead is Mainieri and whoever he puts together. For a while Mike Brecker and Mike Mainieri were the two people and put different other groups together, but it got more and more electric. I’ve no objection to anything electronic, but I was less interested in that at that time.’

You weren’t on Steps Ahead, the 1983 album on Elektra, but it was the recorded debut of your famous tune, Pools.

‘We had been playing that live and then I left the group shortly before that and I guess they asked Eliane to play, and I remember going to her house to show her some things I’d been doing. So that was their first American album and they recorded that tune.’

A wonderful tune, one of the most remarked tunes off that record.

‘That’s probably the tune that people mention most in connection with me. It’s been recorded a number of times. I did it on the Hearts And Numbers album. Woody Herman recorded it. In fact I heard from a trombone player in Woody’s band that towards the end of Woody’s life some nights he would sort of forget the name and he would say “Now we’re gonna do a tune by a young composer, and it’s called Soup.” ‘

‘There are some songs that I’ve written in one afternoon. But something like Pools was more the sort with a couple of fragments’

Can you recall how the tune came about?

‘I can’t, no. And I would say that would be the answer about any of the songs that I write. Most often my method of writing. which is not one I recommend to anybody, is very undisciplined and kind of haphazard. I’m kind of fooling around at the piano, sometimes I’m just looking out the window and not really paying attention, and I may just find a combination of chords or some little melody fragment will suggest itself to me and I’ll go with it for a while, and if nothing seems to be happening too much, if it still seems like something I might wanna recall, I’ll probably write that out. And that fragment may just stay around and I’ll look at that from time to time and play it again. And eventually I may have a number of these fragments that seem to go together in a certain way. Or they can go together if I write another section to link them. So they come together sometimes like that – it can take years. But that’s not the way I always write. There are some songs that I’ve written in one afternoon. But something like Pools was more the sort with a couple of fragments. I also think usually there’s no story with it, or particular emotional scenario. I mean music should have emotion – it shouldn’t be a dry, technical exercise – but the emotion is indirect. It’s not literal, it’s not “You should feel this when you hear this song,” or “I felt exactly this.” It may create a certain mood, but. . . That’s why I always have a problem with people who send me lyrics that they propose for a lot of my tunes. I could see writing a song with somebody and doing lyrics, but most of the lyrics people write after the event for my tunes, they just seem too specifically pinning it down, into a mood that I don’t want. And most of the things I write tend towards a certain darkness, but with a little humorous twist to it. That’s the way I think verbally, usually, and I have a dark sense of things, but kind of a cheerfully dark sense of things. It’s tough for people to write lyrics in that vein. They come out too maudlin.

‘Cost Of Living . . . it’s got this kind of dark, what I call little Russian thing to it’

‘This tune Cost Of Living, which Mike Brecker did on his record and then I did it on Nighttown. That’s a really good example of that, because it’s got this kind of dark, what I call little Russian thing to it that may or may not have anything to do with the fact that I come from that sort of background. But on the other hand there’s a lot of little comic elements – there are quotes from other tunes that are very light-hearted, like Mary Ann, a children’s tune. But people sent me lyrics that are like very sad. To a certain extent, things that might not seem compatible, I like to see if they can work together, though I don’t consider myself post-modern in this way, using fragments of this and this, you know. I like the pieces to have a feel as a whole, but not necessarily’conveying one simple emotion.’

Although you say Pools might have been a collection of fragments, it sounds like a tune that flows out very naturally, with good thematic consistency and development. A sound of its time too.

‘Yeah, and also the bass and tenor taking the melody. The bass was not functioning as a bass, so maybe that had a kind of little Weather Report aspect to it.’

This is perhaps one of the things people are thinking of when they refer to Steps Ahead as an acoustic fusion band taking – Weather Report type textures and rhythms without the wattage and electric timbres.

‘Yes. The very initial gigs were closer to a bebop band, although it always had a little funk thing in it. So it was a kind of a beboppy, funky band, and then it got more synthesised, I guess.’

I never quite understood that shift of policy, because it seemed to be so successful the way it was.

‘I don’t know, ’cause most of that happened after I left. We were on a European tour, it was our first European tour, and towards the end of it we were all asking ourselves “Are we prepared to make a real commitment to this?” And I thought about it and I realised my answer was no. I don’t exactly know what the reason was. Maybe I just wanted to pursue my own things a little more, wasn’t ready to be tied to that.’

‘I was always very proud to have the same birthday as Coltrane, and there are other people with that date whom I’m pleased to be associated with, like Ray Charles, Les McCann and Bruce Springsteen. Then we move on to, I think, Julio Iglesias and Mickey Rooney’

Let’s step back to the beginning a bit. When were you born?

‘September 23, 1947. I was always very proud to have the same birthday as Coltrane, and there are other people with that date whom I’m pleased to be associated with, like Ray Charles, Les McCann and Bruce Springsteen. Then we move on to, I think, Julio Iglesias and Mickey Rooney.

‘I was born in Brooklyn, but I grew up in Levittown, which was . . . When you say that in the States, people have a real idea what Levittown is, especially if you’re a certain age. This builder Arthur Levitt built this place and Long Island at that time was potato farms and duck farming; there was nothing out there, it was really rural. And he built this community of these houses. There were like two or three styles and they all had a nice yard and they were very cheap – about $65 a month to rent or you could buy for something like $6000. It started in 1947 or ’48, and basically soldiers returning from World War Two, especially people who grew up in Brooklyn and the Bronx and dreamed of a house with a yard, and had young kids, moved out there and it was affordable for them. So it became a symbol of a certain kind of suburb. And we were one of the first families there. We moved out there when I was two weeks old and I grew up there until I was 16.

Of the accordion: ‘For a while it was a joke, or seemed unbearably corny. But then some Cajun and Zydeco music, and Los Lobos and a lot of bands used it in a nice way, and I got interested again’

‘I had some lessons. I first played accordion, which was very popular then. I guess it also had something to do with the lack of money. These accordion guys were able to persuade people that if your son or daughter wants to play piano someday but you can’t afford a piano, here’s something that’s like a piano, it’s small, it’s not too much money. And then some day you can move onto piano – and that’s exactly what happened with me. I had an accordion and I played it from when I was about eight until I was 10 or 11, and then my grandparents gave us their piano. And I didn’t touch the accordion again until about two years ago, with James Taylor. He’s always liked an accordion sound, and we’ve done a lot of records where we’ve used a synthesiser to get that sound. And that sound started coming back in again. For a while it was a joke, or seemed unbearably corny. But then some Cajun and Zydeco music, and Los Lobos and a lot of bands used it in a nice way, and I got interested again, so I bought one and was surprised at how much I remembered. I’ve been playing it quite a bit lately. I’ve never played any jazz on it, and I’m not planning to particularly, but I like to play some of this other, Cajun-inspired music on it.

‘So, I began playing piano and had a teacher come to the house once a week for a number of years, a very fine teacher named Ray Thompson. I did not practise as much as I should’ve. I’ve paid my whole life for a lack of a certain kind of discipline, I feel, when I was young. I just wanted to follow my own interest, which was right from an early age in bebop, and I would just play what I felt like playing. I never said to myself if you really wanna have good technique you’re gonna have to practise these other things, even though you’re not interested in it. I was able to get by, I had enough talent or whatever to get by without needing to do that for a long time, and it was only when I was much more of a fully formed adult that I realised I had huge gaps in my technique that are much harder to fill in when you’re older.

’I did do one examination – there was a thing called NYSSMA in New York, a schools music association, and I learned these Gershwin preludes and got a grade 6, which was the hardest, and I got an A, so that was nice, but that was the beginning and the end of my classical career.

‘Then I took lessons for a while with a guy in the city. I lived about an hour from NY and I would take a train in when I was in high school. None of my lessons were classical. The first guy was like pop, learning standards and a little bit of everything. He listened to what you wanted to do and tried to help you in that direction. And I knew I wanted to be a jazz player. We might have done a few classical pieces and a few scales but we went on to standards and learned a little bit of theory. I consider myself not exactly self-taught but a lot of what I’ve learned is self-taught from records.’

‘I always liked the funky jazz composers. . . I loved Horace Silver, Cannonball Adderley, Bobby Timmons and Wynton Kelly. . . I loved Bill Evans, and he was a big influence – but he’s as far in a certain direction of what I would say is more classical or delicate that I like to go’

So, which records were your most important teachers?

‘I was listening, starting around eight, nine or 10, the late fifties, to Miles’s group, Cannonball Adderley, then Trane, groups that had Horace Silver – you know I always liked the funky jazz composers, I loved Horace Silver, Cannonball Adderley, Bobby Timmons (a big influence, played a very bluesy kind of gospel-influenced jazz piano) and Wynton Kelly, an incredible player. I loved Bill Evans, and he was a big influence – but he’s as far in a certain direction of what I would say is more classical or delicate that I like to go. But he’s often misread I think, ’cause he swung a lot too. But I never liked the pretentious kind of music. Of course no-one’s going to say “I like pretentious music,” but it’s what you consider pretentious I guess. I always liked kind of earthy stuff.

‘In arranging – although it was unconscious, I didn’t like study their parts – Charlie Mingus’s things for small big groups were very influential on me. Just the way he was able to write with a lot of structure but keep a lot of looseness. That seems perfect and very hard to do. My voicings for horns, you know it’s mostly things I’m trying on the piano, it’s trial and error, too. I still have not done very much where instruments are playing in all different rhythms you know, and that might be where I fall back on the piano too much, playing block chords. And if I’d studied a little more like counterpoint. . . I remember Nelson Riddle, who died a few years ago and wrote these arrangements for Linda Ronstadt when she did those standards records, and did all those Frank Sinatra things. I thought he wrote very beautifully in that genre, it’s not what I wanted to do, but I respected him immensely. I asked him what he would recommend if I wanted to study something, and he felt he was held back by not delving deeply enough into counterpoint.

‘Oh yes: I should mention that Gil Evans is a hugely influential person for me. I loved his playing and I loved him. He was very complimentary and very kind to me. When I was doing gigs in New York he came to most of them. It was an incredible honour to me that he would come and make a point of telling me that he enjoyed those gigs. I would run into him occasionally and say (’cause if there was anyone I wanted to learn from it was him) we should get together for lunch. And he would say yeah, anytime, and I never did it. I always regret it. I hope I learned something there, that you’ve really gotta do these things.

‘Barry Rogers was an incredible trombonist and a very, very influential musician on a lot of people. I can’t think of someone who got less attention and deserved more’

‘There are two other people that happened with to me: Barry Rogers was an incredible trombonist and a very, very influential musician on a lot of people. I can’t think of someone who got less attention and deserved more. He had a very active imagination and a real thoro’ understanding of all kinds of African music, bluegrass music, all kinds of music, and was revered in the Latin field. He played for many years with Eddie Palmieri, and arranged for him and he was one of the guys who brought trombone to the forefront as a solo instrument in Latin music. The irony to me is that we knew each other for 20-25 years, and right around when he died was when I became very interested in Latin music. There’s another guy, Frankie Malabe, who was a great conga player who died in the last year, and also was a good friend, but I didn’t see him much as I would have liked to. He would have been a great mentor of mine if I’d been interested in that earlier.’

You studied philosophy at university, rather than music.

‘Yeah. I was at Tufts, and very interested in philosophy, but I was a poor and not very serious student at that time. I did a couple of music courses, and I played in the Tufts jazz band, which is the way I ended up meeting Mike Brecker, at the Notre Dame jazz competition in 1967. He came to Indiana University and played the competition with a small group, but they were disqualified because they lifted the curtain behind them during their set to reveal a rock band playing Doors music. There was no small group award that year because they were the best band by far. But Mike won an award as best instrumentalist and I won as best pianist, and that’s how we met.

‘After university I came back to New York and looked up Mike, and he was in a band called Dreams, which had Billy Cobham, Barry Rogers and Randy Brecker and they were not happy with the keyboard player, and I ended up joining that band. John Abercrombie was also in that band, originally. Then he left and Bob Mann joined. So, that was like a jazz-rock band. It was very exciting live, because it was an improvisational band, even the horn section, and we had a singer and it was r’n’b and jazz combined. But Barry and Mike and Randy Brecker were kind of improvising riffs and parts, and they would change from night to night, and Billy was just coming to a certain style. So it was a very exciting band to be in.

‘So that was the first band, and a lot of my career, I would say, led from that, because a number of those people – Billy and Bob Mann and Mike and Randy – were doing a lot of record dates and they sort of got me on some. I’d never heard of that. I didn’t know what a studio musician was and I’d never wanted to be one. But they got me on some dates and it seemed like fun. You’re playing all these different kinds of music, and I started getting interested in some other music. One thing led to another and I just ended up doing a lot more of that work than I’d ever intended to. I found it interesting, it wasn’t like “I’ve gotta do this to earn some money.”

‘But I think it’s just the way most people’s careers go – one thing leads to another. And you might wake up one day and say “Oh, I’ve been doing this for the last 10 years, and maybe I wanna do something else.” I had to do that to make the records I’ve made.’

Was it also the case that there was less session work going round in the eighties?

‘No, I think I can honestly say it was my decision. However, I will say that even if I hadn’t made that decision, the decision might have been made for me anyway. I look at other people who did not make that kind of decision and they’re not doing much studio, they’re always complaining about not much studio work. So some of them were pushed, in a way, into doing more of their own kind of music or going on the road more, maybe playing more jazz. But no, for me it was more. . . You get older and you realise you don’t have forever to do things; you get a little more conscious that there’s a finite period to your life. I realised that there were some things I really wanted to do, and I was getting frustrated, I was getting just tired of that kind of work. I became a little less tolerant of bad producers, or playing with somebody I didn’t respect, and thought perhaps I don’t need to do so much of this kind of thing. So now I just work with a few people I love to work with, like James Taylor, and that seems to have worked out. These days most of my work has been with him and then my own stuff. But the jazz thing. . . from the inside it feels like this is what I’ve always been interested in and doing and writing and playing. I just haven’t been doing records and gigs that much. From the outside, someone looking at my career would see my new jazz projects as a surprise.

‘This feeling got strong in the later eighties. I’d just done one tour with James, and he had another one coming up in a couple of months that it was assumed I’d do, and I found myself one day just calling him up and saying “You know, I don’t want to leave you hanging if there’s no time to find a replacement, but I’m feeling like I need to spend some time really thinking about certain things and writing and trying to do this,” and he was very understanding about it. That was like a real conscious thing, and then around the same time I decided to stop doing like jingles and a lot of the work I’d been doing. I’ve nothing against any of this work. I don’t like to get self-righteous about it, but for me what happened was that if I was trying to write and I’d been doing a lot of other work I just had these other sounds in my ear and it was hard to write. I needed more silence in my life.’

Records

Don Grolnick: Hearts And Numbers (1986, veraBra vBr 20162)

Don Grolnick: Weaver Of Dreams (1990, Blue Note CDP 794591 2)

Don Grolnick: Nightown (1992, Blue Note CDP 07777 98689 26)