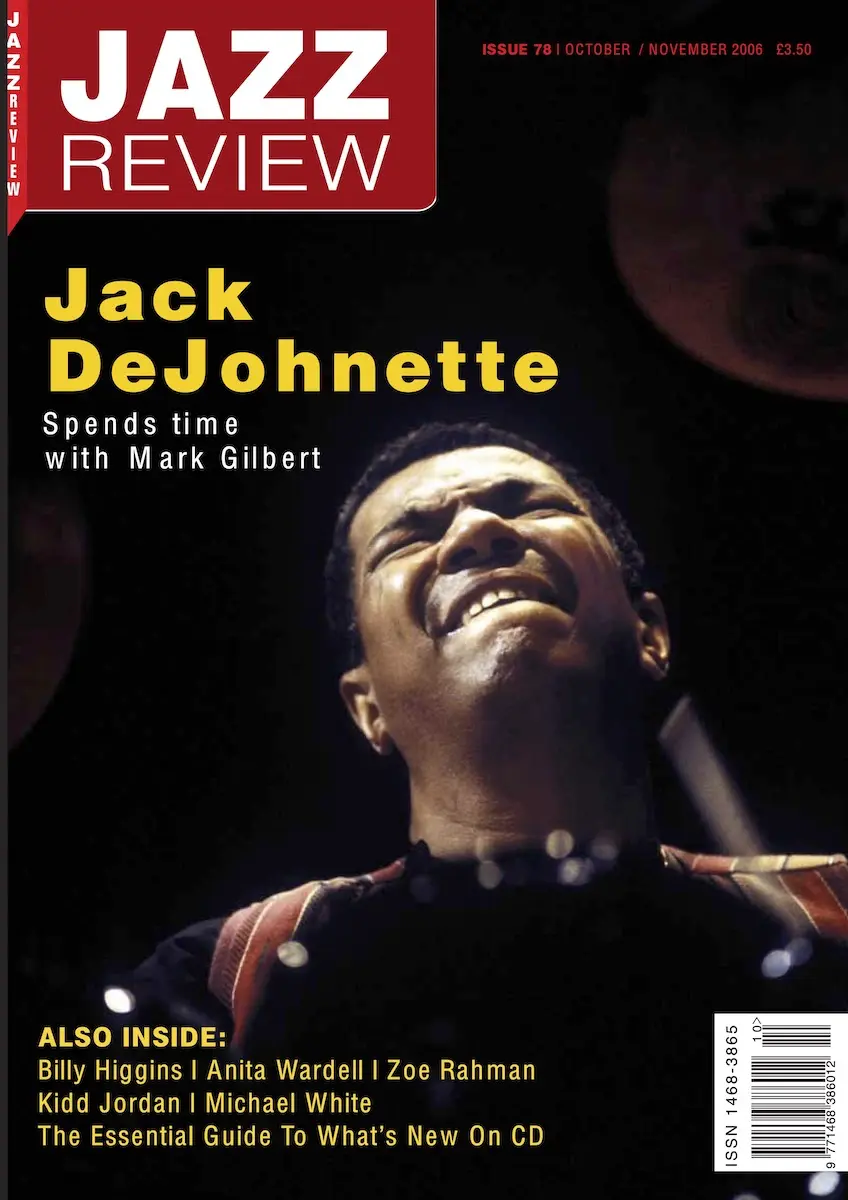

Jack DeJohnette was born in Chicago in 1942 and studied classical piano from the age of four. He took up drums in high school and thanks his uncle, the DJ Roy I. Wood Snr, for keeping him abreast of the latest jazz releases and leading him into music full time. His early professional years were spent in Chicago, leading his own combos and playing in the Chicago avant-garde. In 1966 he moved to New York and played briefly with John Coltrane and Jackie McLean before joining the Charles Lloyd quartet where he found international fame and developed a strong rapport with pianist Keith Jarrett. He played with Miles Davis from 1969-72, after which he focused on leading his own groups and became closely involved with the ECM label, most notably as a member of the Keith Jarrett trio from 1983 to the present. Jack DeJohnette was tested by Mark Gilbert.

KENNY CLARKE

Maggie’s Draw, from Kenny Clarke 1948-1950

Howard McGhee (t); Jimmy Heath (as); Jessie Powell (ts); John Lewis (p); John Collins (g); Percy Heath (b); Clarke (d).

Classics 1214

I don’t know if you’ll know this track because it’s a French recording and maybe not widely distributed – but you might spot the drummer.

That saxophone player sounded like Lockjaw. And that’s probably Kenny Clarke, right?

It’s Jessie Powell on tenor, but yes, Kenny Clarke on drums. Did you study him or any of those bebop players much?

Well, Kenny Clarke was one of the early drummers I listened to because he was the original drummer in the Modern Jazz Quartet, I think. But when I first got into him was on a Milt Jackson record called Opus De Jazz which had Hank Jones, Wendell Marshall [actually Eddie Jones – MG] and Bags. It’s a great record – I still love that record. That was the time when they were talking about Kenny making the shift from that heavy, four-on-the-floor bass drum style to making everything lighter and putting the emphasis on the hi-hat and the ride cymbal. It made the ensemble feel much lighter. So then other drummers started playing lighter like that. Not that he was the only one. There were people like Roy Haynes who did that too. But Max [Roach] still tended to use a four-on-the-floor, a light four, and when he soloed sometimes he’d use the four. But Kenny left that out, and that made more room for the bass to get through and made the music more transparent. Then the other guy who came through and really emphasised that more was Art Blakey. Art had this great swing with the hi-hat and the ride. He had a dynamic, explosive but controlled way of drumming, you know. He got a huge sound out of the drums. But Kenny was one that gets credited with that hi-hat emphasis.

Isn’t four-on-the-floor pretty tiring too?

Not really. The drummers needed it for the big bands to give a foundation to the band. And also, when you play with an organ trio the organists liked to have a little bit of a light four just to give the bass notes a bit of kick. I know – I used to play in organ trios. It’s just a heartbeat you give the band. And then guys used to use big felt beaters, like lambswool beaters. Now they’re smaller and more compact – plastic and hard fibre.

Where did that idea come from – to move the beat from the bass drum to the hi-hat and ride? Was it consciously copied from elsewhere, an unconscious evolution, or what?

It was just a matter of evolution. You know, guys just trying things out, looking for change, the creative spirit that’s in all of us. And as the music changed it required, or allowed, a fresh look at how to play the drums. Guys were playing faster, and more complicated and there needed to be some clarity in the rhythm section.

How did you come to play the drums?

I got in to drums first of all because I had a combo in high school and the drummer left his drums in my basement and I sort of took to them naturally.

Because you were playing piano in the band?

Yeah, I was originally a pianist.

Was that a jazz combo?

Yeah, jazz, and rock and roll. I played all genres of music.

Did you have any formal training as a percussionist, in the school orchestra, perhaps?

Yeah, I played in the high-school concert band and marching band.

And piano?

Yeah, I started that when I was four – mainly classical. But I’m pretty much self-taught as a drummer.

You were growing up in Chicago, a city with a strong jazz and blues scene.

Yeah, well, there’s a strong everything there, really. The jazz scene was there because a lot of guys came up from St Louis and the south. Chicago was the next jumping-off place to New York. A lot of great musicians came from the Midwest. You had Miles, Herbie, Clark Terry, Illinois Jacquet and Gene Ammons, just to name a few.

Why did you become professional?

Well, I knew that’s what I wanted to do. I didn’t have to go through any changes about that. I was drawn to that. That’s what I came here to do.

What did your parents think about it?

Well, my mother and father were separated, but my mother, she wanted me to sing like Nat King Cole. But I wasn’t interested in it. I wanted to play jazz. It was more complicated – but not because it was complicated, just that it spoke to me. She tolerated it, and in a way she supported me because I set my drums up in the living room and had a piano there, and she let me play in the house ’cause she knew where I was. She didn’t have to worry ’cause the music kept me in. So I was involved 24/7 with music. I was listening to jazz when I was four or five because my uncle was a big jazz fan and he later became a jazz DJ. So I had access to all the records. It was through him I got turned on to jazz.

CHARLES LLOYD

Georgia, from The Water Is Wide (1999)

Charles Lloyd (ts); Brad Mehldau (p); Larry Grenadier (b); Billy Higgins (d).

ECM 1734

That’s Charles Lloyd – I know, I worked with him. I just saw him with Zakir Hussain and Eric Harland – we played opposite each other at a jazz festival in Istanbul. It sounds good. I couldn’t tell him right away, but I knew his phrases.

It’s like Coltrane, but more Coltrane’s sentimental side – those crying, sighing tones.

Yeah, it’s out of Coltrane, but he’s got his own thing too. Is that Bobo Stenson on piano?

No, it’s Brad Mehldau. Any idea about the drummer? Charles Lloyd did another album with his name in the title. I think he’s a big fan.

Is that Billy? Ah, that’s why you could hear that kind of singing over the drums – he would do that. Billy’s a great drummer. This is a nice recording. Charles sounds good on it. He used to have intonation problems. His saxophone used to be flat and his flute used to be sharp, but he’s actually playing more in tune now.

That’s a coincidence – you also played with Jackie McLean, another player who always sounded out of tune.

Yeah, Jackie played sharp. He knew it, but that’s how he heard the horn. It was deliberate – he tuned sharp.

It became a really strong trademark – not necessarily a bad one.

Yeah, but also, he put a lot of air in the horn, which made the alto sound like a tenor. He was one of the guys who played the alto but didn’t make it sound derivative of Charlie Parker. Although you knew he was very heavily influenced, the sound was different. He had a more robust, more tenor sound. And his sound was focused and pointed and urgent. Even when he played ballads it still had that edge to it. People loved him, and it was great. He was always about the music first, and he was always about him and his wife Dolly. They had this place in Connecticut and worked with underprivileged kids in the community. Great man – did a lot of good and still does a lot of good.

Did Charles intentionally play out of tune?

Well, it was just the way it was in those times. That was a pretty crazy time. But you know, Charles has had some challenges, some health challenges, a couple of life-changing situations. But now he’s having a comeback and doing this thing with Zakir and Eric. He’s playing all these horns now, like the Hungarian taragato and the alto.

He gave you your first big break, didn’t he?

Well, Jackie was the first one, but internationally the Charles Lloyd Quartet put me and Keith Jarrett on the map.

How did that gig come about?

I started working with Charles with Gabor Szabo. Gabor was great – then he left to form his own band, so Charles was reforming the Charles Lloyd Quartet and asked me about bass players. I told him about Cecil McBee and then he asked about pianists. I told him about Keith. The first time I heard Keith was when he was playing with Art Blakey at the Five Spot, which was still going in the late 60s. I was really impressed, so we got him. We had a rehearsal at Charles’s house and that was it.

That was the beginning of a lifelong association with Keith Jarrett.

Somehow fate has kept me and Keith together. We always had a musical rapport – it was natural. Maybe we played together some other time. We don’t have to talk too much about the music. There’s an understanding. There’s a whole wealth of experience we bring into the trio from other things we do and the trio has also been building on itself for 23 years.

Does it ever get tedious, playing the same kind of music, with the same people?

No. If it did we wouldn’t do it anymore. It’s still interesting.

It’s certainly a strong brand – a good living, I guess.

Yeah, but if it gets like a job, that’s when you go. I do this ’cause it’s my passion. It’s my living, but I come to give something to it and it gives something back.

‘Vamps are great, man. The vamp is universal – in Moroccan music, Indian music, devotional music, funk music and rock music, but you gotta make that interesting’

MILES DAVIS

Hand Jive, from Nefertiti (1968)

Miles Davis (t); Wayne Shorter (ts); Herbie Hancock (p); Ron Carter (b); Tony Williams (d).

CBS 467089 2

Ah yeah, I know that. Great band – Miles, Tony, Wayne. You hear those spaces when they walk? That concept of leaving a space in the rhythm section came from Ahmad Jamal, from the years when Miles was at Prestige and But Not For Me came out. You noticed that all the songs that Ahmad was doing as standards, Miles would then record. When Ahmad would come out with Surrey With The Fringe On Top, so would Miles. Ahmad would play his songs and then he’d leave the space for the drums and bass. Vernell [Fournier] and Israel [Crosby] were such a great rhythm team that he didn’t have to worry. Vernell left space and just swung really nicely in that New Orleans way he played, and Israel had such impeccable time and great choice of notes that you wanted to hear him. Ahmad wanted to listen to that, so he left the space. And Miles picked up on that. The band he had with Philly Joe and Red Garland was like that, and then that carried over into this band. Miles would hire musicians like Tony, myself, Herbie, Chick and Keith because he enjoyed listening to them.

Do you think Miles told this band to play in that Jamal-type way?

No, it just happened that way.

I notice Herbie isn’t touching the piano while Miles is soloing here.

Well, he may have told him on this record, because a lot of the stuff was open. There were no chord changes, and that’s why he wanted Herbie to lay out. And then Herbie, when he played, played single-line notes, just so there would be no harmonic giveaways. Because Miles was also interested in Ornette’s music which was played without changes, but he wanted to have a little more structure. But he really respected what Ornette was doing.

Although he was quite rude about him sometimes too.

Well, he didn’t like the way he played violin, but he did like the saxophone playing. And he liked Don Cherry a lot.

But then Miles seemed to change his opinion quite quickly.

Well, yeah, but musicians like that were always full of surprises and kept coming up with new, interesting ideas. He never got bored with that. He had a short attention span and that’s why you had to really be on your toes, playing with him, with creative ideas. You could feed whatever and he’d use it.

What if he didn’t like what you were doing?

Well, he’d tell you, but most of the time everybody was doing fine. If he didn’t say nothin’ you were doing what you were supposed to do.

Did he direct you much?

Not really. Only once or twice he’d ask me to do something, play a certain rhythm. Like on that record from the Cellar Door that’s been re-released [The Cellar Door Sessions, 1970], on the tune What I Say he sang the drum figure to me just before we played it. Other than that it was left up to me to make up the beats and the grooves. He only directed the band by choosing what tunes we were gonna play, which he would kinda spell out by playing on the horn. It was a sequential thing, going from one tune to another, like the Bitches Brew sessions. He carried that into live performances.

There were a lot of long numbers around in those days. Was that always a good thing?

Well, it depended who was doing it. If you got guys who couldn’t keep coming up with fresh ideas then the audience would get bored. But if you had someone like Coltrane, who could play for an hour or 45 minutes on one tune but always growing and changing, that’s a different story. Not everybody is John Coltrane. So sometimes it got to be long and rambling in that Miles band. But vamps are great, man. The vamp is universal – in Moroccan music, Indian music, devotional music, funk music and rock music, but you gotta make that interesting.

Didn’t Miles get that nicely balanced in the 80s, when he played vamps but with more focus on arrangements and changes?

Yeah, I think Miles put his stamp on that stuff. He started using guys that he directed more. He wasn’t using Keith and me like that ’cause we wanted to keep going and exploring things. I think that band before he died with Kenny Garrett and so forth, it was predictable. It was improvisations, and Kenny played great in that. It was a good foil for him.

And Gary Thomas too, kept the jazz going there.

Yeah, but Gary didn’t play with him that long. He got bored with it. He was playing with me at that time, and Miles told him he wanted him to stay and he told Miles he was bored with it. He enjoyed playing with me more – it was more challenging. Miles kept begging him but he said no, he had no interest in that.

A man of principle!

But I respect that. Miles couldn’t believe it. But I still loved listening to Miles up until the end. I loved that You’re Under Arrest record. I think for what he plays, I loved what he did with Human Nature and Time After Time. It was like he wrote the song, the way he interpreted those melodies.

ROY HAYNES

Rok Out, from Vistalite (1978)

Ricardo Strobert (as); Joe Henderson (ts); Marcus Fiorillo (g); Dave Jackson (elb); Roy Haynes (d); Kenneth Nash (cowbell).

Galaxy 5116

This is kind of old, right?

Yeah, it’s 1978. But this probably isn’t typical of this drummer’s playing. It reflects the period. He’s better known as a swing and bebop player.

That’s Joe.

That’s right. The drummer’s pretty locked in by the groove. He gets a little break in a minute that might help.

I’m trying to figure out who the guitarist is. Sounds like McLaughlin. Alto player reminds me of Oliver Lake but I don’t think it is him. I haven’t a clue about the drummer – the drum set sounds like a cardboard box. That was the sound then, tuned down and muffled, a flat sound.

I don’t think you’d ever guess it from that playing. It’s Roy Haynes.

That’s Roy? Well, he didn’t sound bad. He was doing the job – that’s what the drummer was supposed to do in that kind of music at that time. For him to do that, he had to be disciplined, and that’s to his credit. The only reason I can think for Roy to do that was because he was always a trend-setter and this was new for the time. It’s great to hear Roy doing that, because he’s one of my mentors and close friends, but I would never have guessed that.

I read somewhere that you’re considered to be a stylistic successor to Roy Haynes. Is that right?

I think I built on what he did, but also on what Tony and Elvin and Philly Joe and Papa Jo and all those guys did. Roy’s concept is modern, forward-looking. He was always contemporary and still is. In that sense I can see a connection. There’s a Roy Haynes influence just in my drumming, but it’s hard for you to hear it. There are things that him and Elvin did, because they were both contemporaries. Roy’s certainly an inspiration – I hope I can be as active as him when I’m 80.

BILLY COBHAM

Stella By Starlight, from The Art Of Three (2001)

Kenny Barron (p); Ron Carter (b); Billy Cobham (d).

Blow It Hard BIH010

This recording sounds separated. I’m sure they were in different rooms, but there’s a way you can mix it so that the players sound like they’re more together. The piano sounds like it’s in its own space and you can hear the reverb on it. And the bass sounds really boomy.

This is another drummer who you’re more likely to hear in a different style, so again, he may be hard to spot. He’s in your generation.

Is that Billy Cobham? Yeah, Billy can swing all right, and he’s been doing more of that recently. He’s played with Ron Carter, and James Williams and so on. It’s like Ginger Baker – he comes from that rock background, but did some records with Charlie Haden and Bill Frisell. Ginger said: “I play rock and roll for money but jazz for fun.”

Yeah – Jack Bruce told me once that “Cream was a jazz trio, but we didn’t tell Eric that.”

Well, they helped open things up, and got more jazz guys interested in going electric.

‘Sounds like Dennis Chambers. Another buddy of mine. He’s great. He’s amazing. He’s ridiculous. He can play those grooves really great, and he’s got chops to match’

PETER ERSKINE

Sweet Soul, from Sweet Soul (1991)

Randy Brecker (t); Bob Mintzer, Joe Lovano (ts); Kenny Werner (p/org); John Scofield (g); Marc Johnson (b); Peter Erskine (d).

BMG Novus PD 90616

That’s Scofield – I know him from the first note. I have no idea which record this is – he’s recorded so many.

It’s actually the drummer’s record. We’re short of time, and this one takes a long while to get going, so I’ll tell you it’s Peter Erskine.

That’s funny. I was thinking of Peter Erskine. Peter’s an amazing guy, because he can write and arrange. He usually plays Mr Minimal, like here, but he can open up on the drumset too. He’s a really well-rounded musician and a great person and family guy.

You’ve also done your share of bandleading and composing, and now you’re running your own label Golden Beams. Does that fill a gap not filled by all your other involvements?

It really came about through prodding from my wife Lydia and my younger daughter, Minya. Lydia saw that I wanted to do these special projects and she thought I should have an outlet where I could put out what I want, so it’s a small label. The first CD I did was for the energy work that Lydia does.

Energy work?

Counselling, that kind of thing. She needed something that was calm and relaxing, so I went into my studio and went into meditation and came up with Music In The Key Of OM.

Are you a Buddhist?

No, I’m not into a particular type of religion. They all have something that merits consideration, but I prefer to stay neutral. But anyway, there was this record called The Eternal Om which was a sample of male voices singing – looped thing with this continuous om chant. People use that for meditation, so I based my record on that principle. I did it in the same key, C sharp, and did this drone using the Korg synthesizer and I used a resonating bell which I helped design with the Sabian cymbal company. Then I used another synth to create like a breathy alto patch. My son-in-law Ben Surman, who’s John Surman’s son, helped me with that. That CD actually got nominated for a Grammy in the new-age section last year! It also got some good jazz reviews, which is surprising ’cause I don’t play any drums on it. I find it useful when I’m going to sleep, on the road, or when I’m having a massage, where often the music they play is too loud or busy.

And the second album?

That’s in a different direction. It’s with Foday Musa Suso, the Gambian griot singer and kora player. I call him a really authentic jazz kora player, in the African sense. He lives in Chicago from March till about November, then he goes back home to Gambia, where he has a family. The first time I heard him was on an album recorded in 1974 with Herbie Hancock, called The Village. Columbia didn’t know what to do with it. Then I heard him again with Philip Glass and said we should do something. We jammed and then we recorded in my studio, and Music From The Hearts Of The Masters was the result. We’re coming over here [UK] on tour in December, hopefully, with Jerome Harris. The third album was a remix project called Ripple Effect – Hybrids which was produced by Ben Surman. Ben’s quite a sound engineer, and he took two or three pieces and did some remixes of them. The fourth album is a live concert with Bill Frisell in Seattle in 2001, and that’s called The Elephant Sleeps But Still Remembers. Then we have some things coming up involving DJ Logic and the late, great percussionist Don Alias.

CECIL TAYLOR/GÜNTER SOMMER

Puuc Part 3, from In East-Berlin (1988)

Cecil Taylor (p); Günter Sommer (d).

FMP CD 13/14

That’s Cecil Taylor. Is that Andrew Cyrille on drums?

It’s actually Günter Sommer, the German drummer. Did you ever play with Cecil?

I never played with Cecil, but I did play opposite him in New York with the Gateway trio. That was great, because I got a chance to sit down and hear him every night and really get pulled in to what he was doing. Cecil’s an acquired taste, but what people have to learn to do with Cecil is to not think about the piano as this pianistic thing. He can do that piano thing, but what he’s doing is playing drums on it. He’s playing rhythm, but abstract. There’s a kind of swing in that abstraction, if one dispenses with judgements and rigid rules about what jazz is and what you should expect from it. If you come to it open, without preconceived notions, you find it’s very enjoyable. It’s intense, but it’s enjoyable. He has his quiet moments too. He’s developed his own technique. To play that way, and that long, takes a lot of physical stamina.

DENNIS CHAMBERS

Otay, from Outbreak (2002)

John Scofield (g); Jim Beard (kyb); Gary Willis (b); Dennis Chambers (d).

ESC/EFA 03682-2

Talking of bass drums…

Sounds like Dennis Chambers. Another buddy of mine. He’s great. He’s amazing. He’s ridiculous. He can play those grooves really great, and he’s got chops to match. He’s been playing with Santana recently. I loved him when he was playing with John Scofield in the 80s, with Jim Beard. He’s got big technique, but he’s very relaxed. He sits low and looks very comfortable. He loves to play with creative players. You know, he comes out of that P-Funk stuff, but he gravitated to jazz as well.

He’s got a very striking bass drum sound.

Well, he uses a double beater on the bass drum, so you can play rolls and other complicated things on it, and he has the technique to make the most of that. He’s a pretty amazing guy.

Selected Jack DeJohnette discography

As sideman:

Jackie McLean: Jacknife (1965, Blue Note)

Charles Lloyd: Dream Weaver (1966, Atlantic)

Charles Lloyd: Journey Within (1967, Atlantic)

Wayne Shorter: Super Nova (1969, Blue Note)

Miles Davis: Bitches Brew (1969, Columbia)

Miles Davis: Live-Evil (1970, Columbia)

Miles Davis: Black Beauty (1970, Columbia)

Miles Davis: The Cellar Door Sessions, 1970 (1970, Columbia)

Abercrombie/Holland/DeJohnette: Gateway (1975, ECM)

Pat Metheny: 80/81 (1980, ECM)

Kenny Wheeler: Double, Double You (1983, ECM)

Keith Jarrett: Standards, Vol. 1 (1983, ECM)

Keith Jarrett: Changeless (1987, ECM)

Keith Jarrett: At The Blue Note (1994, ECM)

Keith Jarrett: Always Let Me Go (2002, ECM)

John Surman/DeJohnette: Invisible Nature (2000, ECM)

John Surman/DeJohnette: Free And Equal (2001, ECM)

As leader:

The DeJohnette Complex (1968, Milestone)

Cosmic Chicken (1975, Prestige)

New Directions In Europe (1979, ECM)

Special Edition (1979, ECM)

Album Album (1984, ECM)

Audio-Visualscapes (1988, Impulse)

Dancing With Nature Spirits (1995, ECM)

Music In The Key Of Om (2003, Golden Beams)

Jazz Review, formerly edited by Richard Cook, was incorporated into Jazz Journal in 2009