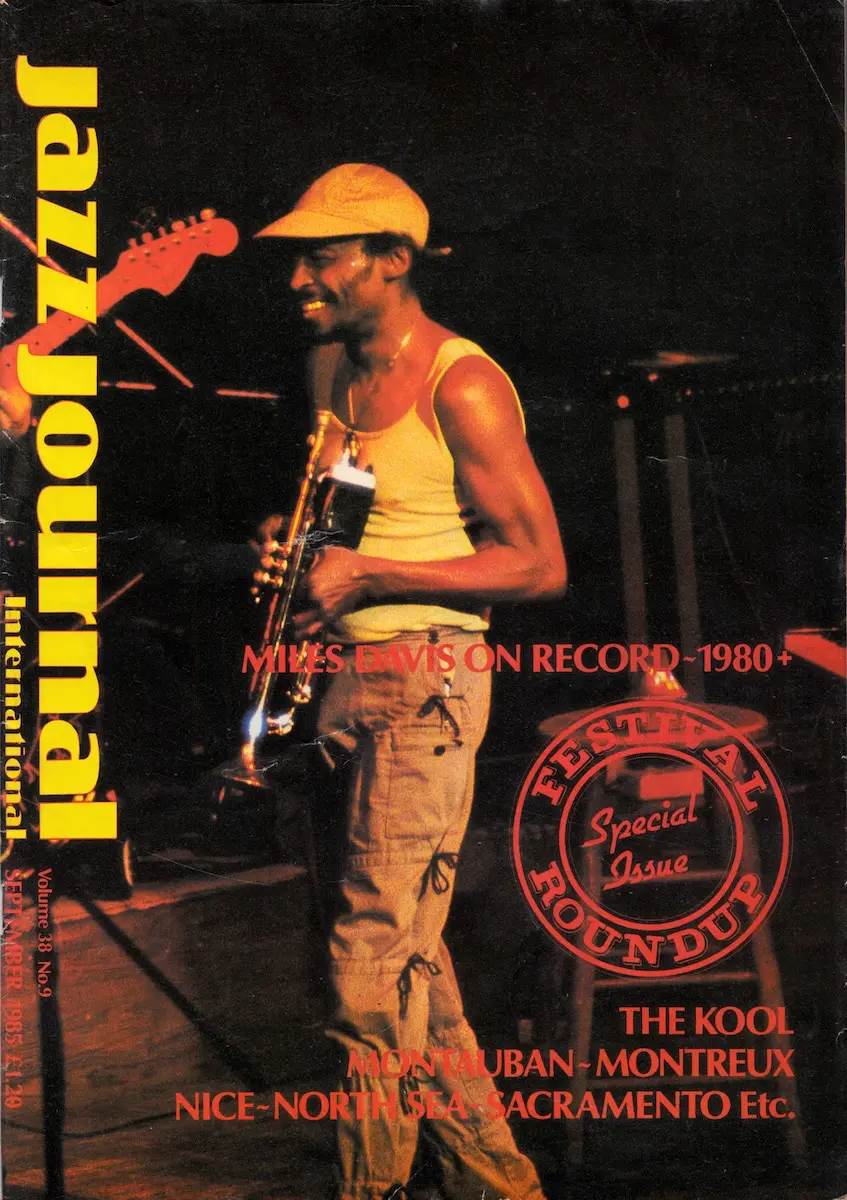

If the title ‘living legend’ were available only as a limited issue, few would dare to challenge Miles Davis’s position at the head of the queue. He qualifies perfectly in terms of age, experience and influence, having been in on the ground floor of almost every development in jazz since the late forties. Furthermore, he has the personality, or persona, to match the description: Since the early days, he has found that the dark cloak of enigma fits him very well and has taken every opportunity to cultivate a corresponding image, both visually and musically. Miles is highly sensitive to fashion, and while this has caused many of his album sleeve portraits to look severely dated in retrospect, it has also meant that his music has undergone almost perpetual change and progress. Unlike the clothes, the music appears to be immune to the ageing process, probably because it has been so widely heard and absorbed that it now seems timeless and fundamental.

In truth, none of Miles’ music is timeless – it can be dated – but it has certainly become fundamental and remains deeply ingrained. Miles’ influence is pervasive, no matter what his opponents or defectors might prefer to believe. This fact must be particularly unpalatable to those who have, at times, thought that Miles was something of a musical charlatan. To such ears, near heretical questions arise, like ‘Why doesn’t he play more melodically when he solos’ or ‘Surely after all these years he could avoid those bum notes?’. But such is the reverence accorded to Miles the guru that minor lapses of taste and technique are usually overlooked or regarded as intentional. Sympathisers might say that he happily and deliberately adopts a fatalistic stream-of-consciousness approach to improvising, thereby producing a more realistic and more balanced warts-and-all picture.

Maybe, as John Scofield once suggested to me, ‘He just lets it happen.’ In any event, bouts of cynical speculation are rendered uncharitable in the face of the crystalline lyricism of So What on Kind Of Blue or the lightly sprung shadow-boxing of Miles’ solo on Something’s On Your Mind from the latest LP, You’re Under Arrest.

Hand in hand with the suspicion that Miles might have done more faking or ‘busking’ than even the most extemporary jazzman ought to, is the notion that he has been at best a conceptualist and catalyst rather than a composer and soloist and at worst a freeloader and plagiarist, attracting record deals solely by reputation and association, offering fame, wealth and exposure to the finest young sidemen and then proceeding to appropriate their talent and ideas for his own glory. One thinks of Bill Evans’ comments in the March issue of JJ about the Kind Of Blue recording date: ‘In a sense, we co-composed Flamenco Sketches that day, but Blue In Green was entirely mine. Now I know that on the album it is credited to Miles but he did the same thing with two of Eddie Vinson’s tunes, Tune Up and Four. It’s a small matter to me but when someone asks me about it, I tell the truth.’

Mark Gridley, in his invaluable book Jazz Styles: History And Analysis, points out that ‘Most Davis recordings made after 1969 list Davis as sole composer in spite of the fact that he was sometimes performing the compositions of others. Zawinul’s Double Image is properly credited on the Davis Live-Evil LP, but his Orange Lady, which is the last third of Great Expectations on the Big Fun LP, is credited to Davis.’ (1)

Miles also takes the credit for the majority of the compositions on his last five albums, but given the way in which the band works in the studio (sidemen have suggested that tunes often arise out of loose jamming) it seems quite possible that many of the recent compositions credited to Miles might have been in varying degrees the invention of his sidemen. Even if all that Miles claims to be his is his own work, the fact remains that to these ears the Miles credited compositions on the last five albums are often the least memorable. Ultimately though, any truth in these suggestions is irrelevant, because the end – the music – justifies the means and if any exploitation has existed, it has worked both ways, to the mutual benefit of leader and sidemen. If Miles functions better as instigator than creator, this role is of immense value in itself, given his choice of players and the direction in which he steers them. At least he is expressly aiming to instigate some new music, unlike that other elder statesman of jazz, Art Blakey.

If Miles can be seen as a kind of interchange for new musicians and their ideas, he enjoys the same kind of position in relation to the various streams of contemporary music, again to the benefit of all concerned. In the late sixties, with In A Silent Way, he began to draw heavily on the mainstream of popular and mainly black American music and has continued to do so since his return to the recording studio in March 1981. Much of his subsequent work has expanded and redefined soul and funk idioms, not least on You’re Under Arrest, which features three recent chart hits as vehicles for personal interpretation and improvisation. Spontaneity, sophistication, iconoclasm and wit are injected into what would otherwise be good soul tunes with unremarkable lyrics. This fusion of popular style and jazz spirit, as well as producing some superb music, can also, in the hands of Miles, be a two-way process, of mutual benefit to both pop and jazz.

All this is fine for those who approve of Miles’ recent output, but perhaps of little comfort to those who felt constrained to get off when Miles went electric in the sixties and who haven’t yet been able to get back on. For them, the last five albums by the Davis band might seem alien, commercial, unsubtle and decidedly uncool. It is the eventual purpose of this discourse to show that since his return to full-time music in 1979, Miles has remained firmly in touch with jazz values while producing new, contemporary music and reconnecting jazz with its roots in black music, even if he sometimes denies his connection with jazz and proclaims its demise. His comments to Frederick Murphy in Encore magazine in the mid-seventies suggest that when Miles reacts against the notion of jazz he’s reacting against a certain period in its history: ‘I don’t like the word jazz that white folks dropped on us. We just play Black. We play what the day recommends. It’s 1975. You don’t play 1955 music or that straight crap like My Funny Valentine . . . That’s the old nostalgic junk written for white people.’ He is also reacting against white convention, though not, it can be argued, against the spirit and principle of jazz. Some later comments to Howard Mandel in Downbeat (December 1984) suggest that Miles has not forsaken that spirit but still actively endorses it. He advises: ‘The way you change and help music is by tryin’ to invent new ways to play, if you’re gonna ad lib and be what they call a jazz musician’. Indeed, rather than dismissing jazz, Davis seems to be defining one of its basic tenets, one which he has applied to his own band over the last five years, and which has helped him extend the vocabulary of jazz. The medium has changed – that is one of the ways the music has moved on – but the message remains the same.

By adopting a different medium, Miles has not only escaped the straitjacket of white jazz convention, but has also, perhaps unconsciously reconnected jazz directly with the black elements in its roots. By embracing funk and soul, he has infused his music with new blood via r&b back through race records to gospel, blues and work songs. Above all, he has remained open to outside influence and concurred neatly with one of Mark Gridley’s observations about the elasticity of jazz: ‘Since the time jazz began, jazz has always shown the capacity to absorb diverse streams of music. The incorporation of rock and funk demonstrated that this capacity had not been diminished.’ (2)

The year of Miles’ return to the recording studio produced material for two albums which, stylistically, are easily twinned. Man With The Horn and We Want Miles were recorded within six months of each other in 1981, and the latter is in a sense a live concert version of the former. At that time, the band was only recently formed, and it’s my guess that this unfamiliarity was the reason for the somewhat skeletal themes and structures on these records. They sound much like open-ended jams, anchored on Marcus Miller’s huge and reliable funky bass playing, which teems with irregular and exciting accents. We all know by now that syncopation is a prerequisite for jazz and the following comments by Mark Gridley about funk and soul rhythms vouch for their jazz credentials: ‘During the late 1960s, black styles which extended r&b became the source for intricately syncopated drum patterns and complementary bass figures.’ (3) In harmonic terms, the material on these two albums is by and large modal. There are few key changes, and this approach echoes the style that Miles was instrumental in founding in the late fifties. The rhythmic framework is different, but nevertheless contains the essential ingredient of extensive syncopation.

These early albums stick close to the conventional ‘blowing’ ethic, with plenty of collective and solo improvisation and only sketchy arrangements. Miles tinkers with a Fender Rhodes occasionally on We Want Miles, but otherwise there are no keyboards or synthesisers, and only open or muted trumpet, free from electronic alteration. As a result, the music seems relatively faithful to small band style, albeit electric. Of the soloists, guitarist Mike Stern is outstanding, though much maligned by critics who recoil aghast at his rock tone and phrasing. Miles much admired Jimi Hendrix, and it’s true that he sometimes required Stern to play like him, but to think that this is all there is to Stern’s playing is to underrate and malign him. He is also capable of virtuosic bop-through-Coltrane jazz playing, and can be heard to great effect in this capacity on My Man’s Gone Now on We Want Miles. This track also features Miller’s rock-steady walking bass.

Star People was released in 1983 and though much of it suffers from poor sound and balance, it is significant in marking the introduction of rather tighter arrangements, which led, on later albums, to quite complex ensemble manoeuvres. It also saw guitarist John Scofield’s debut in the band – an addition which immediately and subsequently proved to be profoundly important. Scofield, like Miles, is steeped in the modern jazz tradition, from bebop onwards and his solo work as epitomised on Star People’s Speak has all the essential qualities of jazz improvisation and more. He swings, he invents, he twists, warps and paraphrases both the traditional vocabulary and his own ideas. He is intensely and spontaneously creative in a way that satisfies all the criteria of jazz performance. More than this, he incorporates influences from other genres, extending the range of expression available to the improvisor, while using jazz as his starting point. The arrival of such a consummate and original soloist confirmed that improvisation was still of paramount importance to the renascent Miles, and Star People’s title track, a marathon blues with long solos from Miles provided further evidence of his continuing jazz fealty.

It’s indicative of Miles’ appetite for change and novelty that there is a great diversity of style and content in these last five albums and this is nowhere more obvious than on Decoy, which was released in 1984 and was markedly different from its predecessor. For one thing, it brought personnel changes, with the inclusion of the obliquely minded Branford Marsalis, who makes an unearthly solo contribution to the title track, and the reappearance of Robert Irving III, who had last featured on Man With The Horn. In addition, Darryl Jones took up bass duties where Miller and Barney had left off. Decoy also signalled a dramatic increase in ensemble arrangements, had cleaner playing and sound and much richer textures. It seems likely that Irving was responsible for many of these developments. Harmonically, the record followed the style of the earlier albums, remaining true to the modal principle and avoiding complex key changes. Again we can note the close similarity between the modal harmony that Miles espoused in the fifties and the static harmony of the typical funk rhythm section. Miles’ 1985 harmonies are as simple as those he used in 1959, and form the basis for equally complex and inventive syncopation and improvisation. A case in point is Robert Irving’s Code M.D. on Decoy, which has long passages that make extensive use of just two key centres, G and A minor. So Miles’ harmonic structures have altered little since 1959; the developments have been in the rhythm section, the textures, instrumentation and the soloists’ vocabulary.

You’re Under Arrest, the fifth of the famous five, is probably the album that has caused most discomfort to the nostalgist, perhaps because of Miles’ desperado posing on the sleeve, or perhaps because the album features three recent chart hits. Yet, paradoxically it’s this album that brings Miles, and jazz, full circle, by reconnecting them both with their roots in popular black music, which is closer to the origins of jazz than much of the music that claims that name today.

Furthermore, as my review of You’re Under Arrest in the July issue of JJI pointed out, pop tunes have always been fair game for jazz improvisation and that’s their purpose here. Under Miles’ tutelage, they become more than pop tunes; indeed, the likelihood of Arrest’s version of Something’s On Your Mind getting into the top 50 is as remote as the likelihood of Bucks Fizz being invited to do a session for BBC Jazz Club. Scofield’s lunatic solo precludes that possibility.

The evidence in this article of Miles’ continuing involvement with jazz might easily be ignored, but cannot be refuted. If the constituent elements of Miles’ current music – invention, syncopation, improvisation and swing, among other things, don’t qualify it for the name jazz, where does that leave something like Kind Of Blue? Over and above the technical evidence, Miles’ own personality displays a characteristic which has been common to all the key figures in jazz and that’s the perpetual search for singularity. Never satisfied simply to reiterate his own or anyone else’s inventions, Miles has throughout his career rejected established paradigms and tapped into novel forms of expression in this quest. As a result, his output has been consistently innovative while still remaining Miles – time after time.

References

(1) Mark C Gridley: Jazz Styles: History and Analysis, p 322

(2) op. cit., p 339

(3) op. cit., p 313-316

Discography

Man With The Horn (CBS 84708)

We Want Miles (CBS 88579)

Star People (CBS 25395)

Decoy (CBS 25951)

You’re Under Arrest (CBS 26447)