The average punter is about as likely to get into Ronnie Scott’s club wearing a three-quarter length jacket as to shake hands with Miles Davis, but the door to his sidemen is usually wide open, especially if you’ve got the key…

Over the North Sea Festival weekend in the Hague, you can be sure to find at least one of your favourite young American tenor players ‘hanging’ in the lobby of the Bel Air Hotel. It was there that I met Miles’ current saxophonist, Bob Berg, and suggested we do an interview. At first he seemed largely unmoved by this sensational opportunity, but thought the next afternoon might be OK. The problem was that I had to be in Amsterdam then, and in any case I was anxious to land this fish while he was hooked. It had to be tonight. It looked like no deal, until along came that other star that sparkles in Miles’ firmament – John Scofield: ‘Hey Bob, this is the guy who did the greatest article about me.’ Bob: ‘Hmm… look, perhaps we could do this thing tonight.’

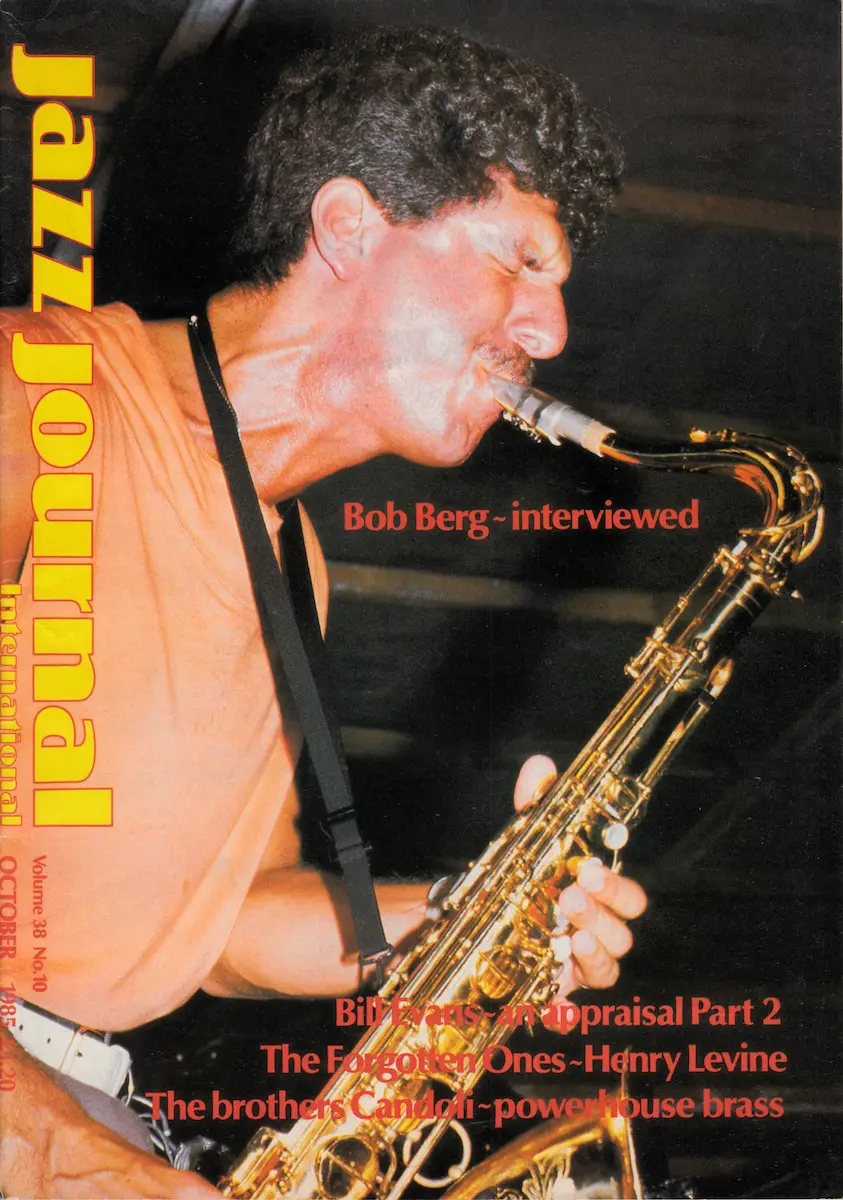

‘Bob Berg, figure essentielle dans la generation actuelle des tenors newyorkais.’ So runs the quote from Jazz Hot magazine on the sleeve of Steppin’: Live In Europe (Red Record VP A 178), one of the latest releases to feature Bob Berg. This accolade will seem entirely appropriate to many listeners, especially the musicians among them. Indeed, Berg’s talent was spotted and eagerly snapped up last year by the ultimate arbiter of musical good taste – Miles Davis.

Yet full recognition has not come quickly or easily for the 34-year-old reedman, who took his first major gig 12 years ago when he joined Horace Silver; he subsequently spent around five years with Cedar Walton. He’s done more than his fair share of dues paying, and in more ways than one: He’s also paid the emotional, physical and artistic price of maintaining a full-time heroin habit. His addiction was its feverish height while he was with Cedar Walton and if his solo work at that time was ever tinged with melancholy and self-pity, it always displayed those qualities of persistence and hope which eventually delivered him out of darkness. Berg’s improvisations have always been something special, but since 1982, when he came ‘clean’, his range of expression has widened and his playing has become more controlled, considered, intelligent and mature. As in earlier years, his music has mirrored his real life situation.

Berg’s hotel room faced the marquee that was the North Sea Festival’s Garden Pavilion, and as we sat down to talk, Lee Ritenour’s ‘fusion’ music drifted in on the breeze and assumed an appropriate role as incidental music to the real drama of Berg’s life story.

It seemed to me that Berg’s career was not very well documented, at least as far as Leonard Feather’s Encyclopaedia of Jazz was concerned.

‘Well, it seems like Leonard Feather has somewhat ignored me. I was playing with Horace Silver when I was 22; that’s like 12 years ago, and that was a visible position to be in. OK, it’s not Miles, but still at that time it was one of the good working bands in the States.

‘But I feel like I’m pretty much visible within the spectrum of musicians. As far as the public is concerned, I’m not as visible. I think that’s partly because of what I’ve been involved in, which has been more of a straightahead type of jazz, not so much of a fusion thing.’

So the Silver gig was your first significant job?

‘Yeah. I did others, but that was the first I stayed with. Before that I went to the High School Of Performing Arts, which I never graduated from, because I was a bad boy. I got accepted into Juilliard on a special non-academic totally musical programme. I went there for a year and then I quit that too. I was basically a rebellious kid. I was 18 and I was still a kid when I was going there.’

‘I come from a working-class neighbourhood in Brooklyn, from a Jewish/Italian family and they didn’t know anything about jazz. I never heard jazz at home. To them it was so foreign, I don’t even know if they could be against it’

To learn about jazz?

‘Well, I think to please my parents. I started listening to jazz when I was around 13. I got into the band in junior high school and we had a teacher who was into jazz, a saxophone player. And he laid a few records on me. That was the first time I heard jazz and I immediately fell in love with it. I started buying records, buying what I liked. At that point it just seemed that there was no question that that’s what I want wanted to do. My parents weren’t exactly behind me when I wanted to play jazz, but I see that they were very supportive in their own way. I mean, I come from a working-class neighbourhood in Brooklyn, from a Jewish/Italian family and they didn’t know anything about jazz. I never heard jazz at home. To them it was so foreign, I don’t even know if they could be against it. But they saw I had talent and said “Be a musician, that’s fine.” At the same time they wanted to protect me. They wanted me to get an education so that I could teach if I had to. Now, if I want to teach, I can teach without that education. I got another kind of education.

’I was so unconsciously rebellious at that time that anything they said, I’d go against it. I left home and I quit college both at the same time. I was just a messed-up kid. I really was.’

At that time, in the early sixties, you must have heard the Beatles?

‘Yeah, I loved the Beatles at that time. I really dug ’em. I actually still like ’em.’

So how did you feel about the fusion thing of the seventies – Weather Report and so on?

‘I was really against it. I had started listening to Bird and Coltrane and Miles and Sonny Rollins. Then when I was 15 or 16 Trane was into the free stuff, and I thought wow!, that’s it, that’s where it’s going. So I got into free jazz, experimenting with drugs and all that. I think basically it was youth, not really knowing who I was – which I still have a hard time with – and trying to find something, to find whatever I was. Which I’m also trying to do – but I’ve found it a lot more now.

Playing with Cedar Walton: ‘It started a big controversy around New York, because I was the first young white guy they had ever hired … I felt a lotta heat, and so did Cedar. But it worked out really well. It’s just a perfect example of music transcending all the bullshit, all the politics and all the hatred’

‘Then I got totally sick of free jazz and went back and really studied the classics, like fifties Miles and Coltrane and the Bird things. I was a really closed person at that point in my life, and by the time I was with Horace I was into acoustic jazz very heavily. I got into the bebop thing and just wanted to play in that idiom. So when I got the Horace Silver gig it worked out OK. That was 1974-76; I made three records with him and that was really the first chance I got to record. They’re good records, though not my favourites. Then I quit Horace and started playing with Cedar Walton. I recorded with him a lot, on Timeless and Steeplechase. My favourite record with him is called Eastern Rebellion 2, with Sam Jones and Billy Higgins. That was the first time I recorded with them. George Coleman had left the band; they had heard me with Horace and I sat in with them one night and they really liked me, so I was hired. But there was already another sax player in the band and he didn’t really fit with the music – he quit that night.

‘That started a long association with Cedar and Billy. It also started a big controversy around New York, because I was the first young white guy they had ever hired. And I was playing that real kinda hip acoustic jazz; there was a whole clique around it and I was really an outsider. I felt a lotta heat, and so did Cedar. But it worked out really well. It’s just a perfect example of music transcending all the bullshit, all the politics and all the hatred.’

There seems to be quite a change in Berg’s playing during those years with Cedar. Did he think his playing had developed in any way he could identify during that period?’

I hope it’s gotten better, and hopefully it’s becoming more me. I’m getting a chance now with Miles to get into me more.’

Had he been aware of playing out of certain people along the line?

‘Mainly Coltrane. But I’d say three main people: Coltrane, Wayne Shorter and Sonny Rollins. Rollins and Shorter maybe aren’t that evident in my playing but they are to me. But as with most tenor players of my generation, the Coltrane influence is real strong.’

So what of Jazz Hot’s idea about the current generation of New York tenorists? Later in that sleeve note there is a reference to ‘that limited group of young, and for the most part, white, saxophonists who continue to renew the great tradition of the modern tenor sax’. Presumably this group includes Michael Brecker and Bob Mintzer and people like this? Was Bob aware of belonging to that school of players?

‘Yeah, very much. Those guys are like my best friends on the music scene. Mike and Bob in particular. We see each other a lot and talk about music and everything. So I feel a real kinship to them and they feel it with me too. We all came up around the same time and all came out of the same kind of thing, although everybody’s gone in different directions.’

Brecker’s the one who’s achieved most prominence. I’m not sure why…’

Well, first of all he’s probably the greatest virtuoso the instrument’s ever seen. He’s phenomenal in that way. He’s also real adaptable, a real top-notch all-round musician. I love his playing. I really dig Mintzer too. He’s a great writer. I think we each have our strengths, but it’s weird. I talk to Mike sometimes and he says he loves the way I play; says I’m his favourite tenor player. And I feel pretty much that way about him. It’s funny, ’cos we envy each other, we love each other, we’re afraid of each other. But man, if the shit gets really bad, we call each other up and say what we’re goin’ through. That’s something that I feel is so good about the New York scene. We’ve finally reached a point of maturity where we can be real with each other, not put on airs.’

Who else might belong to that group of players?’

I guess Dave Liebman; I’d say Bill Evans, Steve Grossman… great player. At one time, everyone was afraid of him. He was the cat. And he still plays his ass off. He’s a maniac, but I love his playing. There was a guy named Larry Schneider (all these Jewish guys!); there’s Bob Malach too.’

‘I hear Mike Brecker play some of my stuff, I play some of his. But what kills me is that we all got most of it from the same place – Trane, Joe Henderson, Shorter’

Are you aware of having copied licks from these players?

I think we all copy from each other. I hear Mike Brecker play some of my stuff, I play some of his. But what kills me is that we all got most of it from the same place – Trane, Joe Henderson, Shorter – you know. It’s come out differently in each case, but when they make comparisons between us, they think we’re getting it all from Mike because he’s so widely heard, but it’s not true. I take things from Mike, but the overall concept comes from something else – the same place as his has come from.’

This is the way history is miswritten – because a person is prominent, it’s often assumed automatically that he invented the thing he’s famous for…

‘Yeah, and I think Mike would be the first to admit that. We all get from each other. That’s the beauty of it. When I go and hear Mike or Mintzer play, I learn shit. I take it, it comes through my filters and becomes mine. They do the same thing and channel it in their own direction. Each person has his own strength. One might be lyricism, one might be virtuosity, one might be compositional technique. It’s incredible among a small group of people what evolutions can occur.’

In technical or theoretical terms was there anything Berg had particularly aimed to perfect or had he just covered the whole lot?

‘I don’t think I’ve covered any of it! I read average; I can hear things, I’ve played pretty much by ear. I’m quick – I can hear a set of chord changes a few times and start to make music out of them. Though I could read them too. But as far as methodical study goes – no. I hate to say it, and one day I’ll sit down and practise. There’s a lot of shit I wanna do that I’m not. But it’s weird – sometimes I think I’d like to sit down and learn all the Coltrane stuff – all the chromatics, the substitutions. But then I think to myself “After I’ve learned all that, what am I gonna do with it?”‘

‘I feel like I’d rather stumble around sometimes and find some shit. Miles Davis, man – great example. The cat is totally intuitive about what he does, I’m convinced’

Play like Dave Liebman?

‘Hey yeah! He’s got it all; he’s amazing, a real studied cat. But I feel like I’d rather stumble around sometimes and find some shit. Miles Davis, man – great example. The cat is totally intuitive about what he does, I’m convinced. The cat is such a genius that he makes it work. He’s so sensitive… that’s what it’s about… it comes from sensitivity. I’m a lousy teacher, because I never know what to tell people to play. I can point out what they’re doin’ wrong, but to tell ’em what to play seems hypocritical. Sometimes I feel like “maybe this guy’s really a genius and for five years he’s not gonna be able to play the shit he hears because I told him you can’t do it.”‘

Scofield seems the same: technically very accomplished, but he always seems to be going for something which he doesn’t always get. He’s on the edge, which is great.

‘Yeah, which is to me the excitement of music – being on the edge. I lived on the edge in other areas of my life for a long time. I stopped drugs about three years ago – totally stopped – no alcohol, no drugs. It’s great, I feel so much better. I see what it does to people and it makes me that much more grateful that I don’t have to do it. Music is now my way of living on the edge.’

‘Miles called and wanted to hear me at a rehearsal. I was nervous as hell, but I had nothing to lose. So I went in there, played a few notes and Miles stopped the shit and said “Let’s go in the studio”‘

How did you get the Miles gig?

‘Bill Evans had left the band and Miles was looking for somebody. He had gone through several people, one from Denver, one from Chicago, a couple from NY. I’d been in Sweden for four months; my wife lives there, and she’d just had a child, so I’d been with her. When I came back to New York I didn’t have a helluva lot of work, so I called everybody I knew, including Al Foster, who’s been a friend of mine for years. A couple of days later, Miles called and wanted to hear me at a rehearsal. I was nervous as hell, but I had nothing to lose. So I went in there, played a few notes and Miles stopped the shit and said “Let’s go in the studio”. That was it. It was real simple.’

What’s it like to be playing in this electric context after so long with acoustic music?

‘To be honest with you, I needed a change. I was looking for something like this anyway, and I always felt I had the ability to do it, and not just play straightahead jazz. I feel like I play straightahead very well; I swing, I got a good feel, decent ideas, but I felt I wanted to get involved with something a little younger – even though Miles is 60! And I really feel comfortable with it. Playing with Miles is different from being in a fusion band because you don’t have to play funk licks. He wants me to play different kinds of things, with that kind of a feel going on, because the rhythm section is basically a funk rhythm section; they’re not jazz players. But it’s not a fusion band. When I hear that I think of clichés.’

Like Lee Ritenour?

‘That’s like easy listening. I like it, it’s great music and I respect those people. They are all great musicians.’

What about your horns?

‘A Selmer Mk 6 tenor and soprano, with Dukoff mouthpieces and whatever reeds work, usually La Voz mediums. I’m not one of these guys who’re crazy about trying a different million things. If I find something that works, I’ll use it.’

Berg is listed as appearing on three tracks on Miles’ You’re Under Arrest album, yet he only appears to solo on the title track, and then only for about 25 seconds.

‘I was a little disappointed with that, but we did a bunch of recording and a lot of the stuff that me and Al Foster were on wasn’t used. It’s in the can somewhere. Miles called me one day and said “Man, you played a great solo on D Train” (that’s what he calls Something’s On Your Mind). Then the record came out and it wasn’t there. Maybe it was too jazz sounding, but at least I’m on there; and at least it’s 25 seconds that I’m not totally ashamed of. Though it’s not my favourite shit – I’ve done better than that. Plus, the mix sucks; I know I sound better than that. But at least I hope my playing is somewhat consistent. In fact I feel that’s one of my strengths – I always play something decent.’

‘I’m insecure about my playing, but then I don’t know many good musicians who aren’t. I think that’s part of growth too. I think that once you feel totally satisfied with what you’re doing, you’re gonna stop growing’

And how about Steppin’, on Red Records?

‘I haven’t heard it, and I was a little annoyed that they put it out. I did it for a friend of mine, the guy who produced it, and it was a ridiculously slapdash club recording on a four track. I had just kicked drugs about a week before and I was still going through withdrawal and drinking a lot. Since I’ve straightened up, my sensibilities have changed. I know a lot more about music now, and I don’t think I would get into a situation like that again. Now I want the optimum situation to record. I’m known enough now to be able to do something. I wrote all those tunes during the week before the recording, just as my feelings were starting to comeback. I remember the tunes, but I haven’t played ’em since. I gotta hear them, but I’m afraid to hear them. I was very sick then; it was 24-hour anxiety except when I was playing.’

Berg’s drug addiction looms large in his career, and while it was obviously a handicap, it was also part of a tortuous voyage to self-discovery and maturity.

‘Heroin and methadone were the main ones. They kind of pushed everything else out of the way. Then I went to alcohol. For six months I drank a quart or quart and a half of cognac a day. I was on methadone while I was with Cedar, and I was functioning, but it just got to be too much. I weighed 35 pounds less than I do now. Now I do my 60 pushups and 60 sit-ups a day and keep myself tight enough to look somewhat decent. But then I didn’t have to do anything except wake up in the morning and get a shot of dope. I’d look in the mirror and think I looked great.

‘Heroin makes things seem easy in the beginning, but when you get the habit and it becomes a case of getting it every day or being sick, then it becomes a job. But I learned a lot from it. I learned that I’m not as strong a person as I thought I was. And then I learned that I’m a lot stronger than I thought I was. When it comes to drugs, I’m totally powerless; but if I don’t pick up the drug, I have quite a bit of power.

‘Above all, I learned that there’s nothing so bad that I have to get high over it. There’s nothing in the world that being high is gonna make any better. All it’s gonna do is put it off for another day. Now, I’ve put so many days together clean that I don’t wanna lose the time I’ve got. I feel like it’s money in the bank. I grew up in the last few years. I had really been in an infantile state, and I still am a lot of the time when I don’t get my own way, but I know that if I get high I can’t do anything about it.

‘The only barriers for me now are the internal ones. I’m really insecure about a lot of things. I’m insecure about my playing, but then I don’t know many good musicians who aren’t. I think that’s part of growth too. I think that once you feel totally satisfied with what you’re doing, you’re gonna stop growing.’

Bob Berg on record

There are, for me, at least two distinct and paradoxical yet complementary facets to Bob Berg’s personality, which manifest themselves directly in his music. Since his working-class days in Brooklyn, he has developed a veneer of conformity, but there still seems to be an uncouth youth bristling beneath the controlled exterior; and it’s this rough-hewn, abrasive and hard-bitten side which demands attention when it’s allowed full rein in his music. On the other hand, he is no stranger to despair, anguish and self-loathing, and these are the emotions that lend much of his late seventies/early eighties work a quality of aching entreaty and tearful poignancy. But whatever Berg’s frame of mind, self-expression always triumphs. As he admits, he might be unsure about many things, but he’s pretty sure that he can always ‘play something decent’. Above all, he always plays with great immediacy; his music is like an open book where we can read an unabridged exposition of the human condition.

As the accompanying selected discography shows, Berg has recorded prolifically over the last 10 years and most of his recordings have been with a group of musicians whose common point of reference is pianist Cedar Walton. Those recordings were cast firmly in a straightahead acoustic mould, and it’s only since he joined Miles Davis last year that Berg has been heard widely in an electric funk context.

The earliest record featuring Berg in this writer’s collection is the January 1977 Eastern Rebellion 2, which Berg has said is his favourite record with Cedar Walton. It is composed entirely of original Walton compositions, including the side long Sunday Suite which not only runs through swing, Latin and ballad territory, but also contains typical examples of Berg’s playing at that point. All his recordings show him to be a master of that ‘crying’ sound, but the cry here is one of pain rather than joy.

Third Set, recorded later that year by the same quartet of Berg, Walton, Sam Jones and Billy Higgins, has Berg ploughing a similar emotional furrow. The early sixties Trane influence is obvious, but Berg seems tighter, more coherent and more simply immediate than his mentor often was. As always, his playing is highly charged, but he doesn’t display the invention, individuality or modernity that became evident in later years, and which is well illustrated by Steppin’, recorded in December 1982, but only released earlier this year.

As Berg discloses in the interview section of this article, he had resolved to finally kick the horse only a week before this recording, and was trying to fend off withdrawal symptoms with heavy drinking. For all this, his playing is not only as articulate as ever, but changes in idiom and solo style are evident: His change of attitude to his drug habit was reflected in developments in his music. Although Steppin’ has one straightahead swinger – the Rhythm changes title track – the rest of the record features backbeat shuffles and soulful ballads, while Berg’s solo work displays many modernistic post-Coltrane elements. Particularly worth hearing is Berg’s cliffhanging negotiation of the blues-type changes of Tom Harrell’s Terrestris. This track is also an excellent example of the way Berg exploits the tenor’s full range, from bullish bellow to feline scream; always with style, taste and intuitive musicality.

By the time Eastern Rebellion 4 was recorded, in May 1983, Berg was striding confidently to renewal without his opiate crutch. Sample the Latin Manteca to hear just how intelligently he constructs a solo, and how he extracts the maximum drama from the simple modal situation. His playing is suddenly more mature; he has gained perspective not only on his own life, but also on the music, and he examines the harmonic material with a new zeal and urgency, while simultaneously showing more control than previously.

You’re Under Arrest brings us up to date, and even though it only contains a 25-second snatch of tenor solo, it is a gem of fleeting brilliance, which, if any reassurance were necessary, proves that Berg is still moving up.

Selected discography

Horace Silver: Silver ‘n’ Brass

(Blue Note LA-406G) Horace Silver: Silver ‘n’ Wood

(Blue Note LA-581-G) Cedar Walton: Eastern Rebellion 2

(Timeless SJP 106) Cedar Walton: Eastern Rebellion 3

(Timeless SJP 143) Cedar Walton: Eastern Rebellion 4

(Timeless SJP 184) Cedar Walton: First Set

(Steeplechase SCS 1085) CedarWalton: Second Set

(Steeplechase SCS 1113) Cedar Walton: Third Set

(Steeplechase SCS 1179) John McNeil: Embarkation

(Steeplechase SCS 1099) Kenny Drew: Lite Flite

(Steeplechase SCS 1077) Sam Jones: Visitation

(Steeplechase 1097) Sam Jones: Something In Common

(Muse MR5149) Sam Jones: Changes And Things

(Xanadu 150) Bob Berg: Steppin’

(Red Record VPA 178) Billy Higgins: Soweto

(Red Record VPA 141) Billy Higgins: Once More

(Red Record VPA 164) Miles Davis: You’re Under Arrest (CBS 26447)

Yet to be released: Cedar Walton: (Red Record VPA 179)