Unlike rock and pop music – I think those two labels cover the gamut – jazz is not everywhere. It is so not-everywhere that you often have to seek it out or hope that, in a sense, it will seek you out.

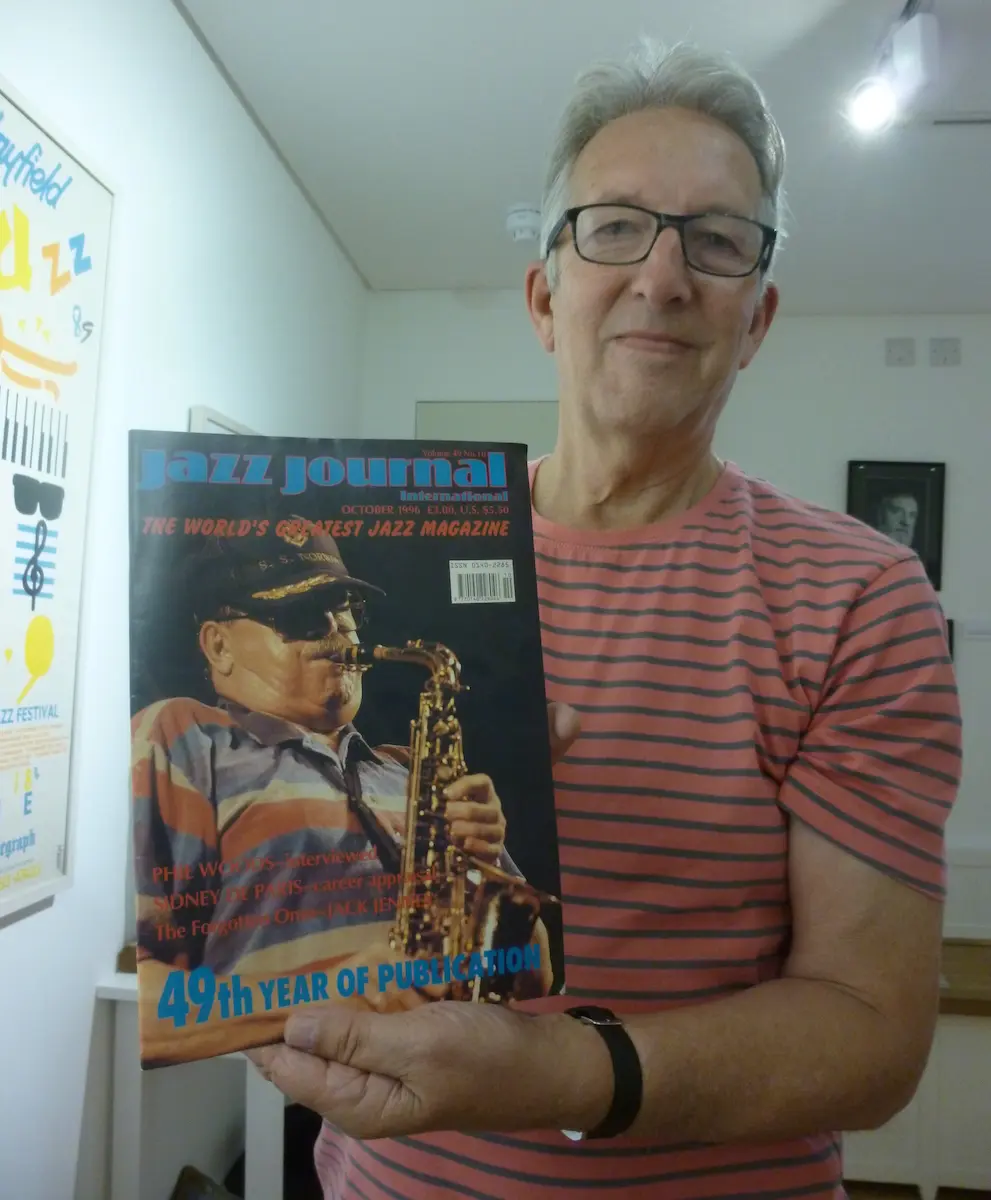

As I mentioned briefly in a print issue of JJ a few years back, it said “Boo!” to me in St Ives, Cornwall – to be precise, at the Leach Pottery up the hill from the town’s long-lived jazz club. In a small room was an exhibition of jazz memorabilia, curated (they didn’t use that word then) by someone clearly in thrall to the music and including a fanned-out display of Jazz Journals, one of which I fingered for the photograph displayed here.

The weird thing was that no-one looking after the place – where Bernard Leach & Co had once revolutionised British ceramic art – could explain what it was or why it had been set up. I now think that it was only in the process of being set up and I, with my journalist’s antennae starting to oscillate in its direction, was its first and technically trespassing visitor.

Among other exhibits were posters about what was on at the St Ives club and other more far-flung locations; and books, including copies of Jazz Book Club titles. The latter included the 1958 edition of Concerning Jazz, by our own Sinclair Traill, whose parting comment was interesting, and worth a reminder in September 2025. Referring to “modern jazz”, he opined: “Most of the better jazzmen who have grown up with modern jazz in Britain have partially (sic) forsaken it for leadership or participation in big bands and bigger money. One cannot blame them. It is perhaps asking too much to expect anyone with talent to exist at the starvation level required by modern jazz club earnings.”

Well, times have changed a bit, even in the western fastnesses of Cornwall.

I had to pick up the book to read that, though I transcribe it now from my own copy; ditto, the 1962 version of Essays On Jazz by Burnett James, a writer recommended to me for his intellectual clout and catholic tastes in music. James was also a classical-music critic, and regularly dropped names from that zone at a time when the conductor Ernest Ansermet’s endorsement of Sidney Bechet was the sole cachet from the non-jazz community that made the music more widely acceptable. If he liked it, there must be something to like.

There were other personal items, including jazz concert tickets, and a battered cornet that may have been intended as a simulacrum of Louis Armstrong’s valveless instrument, on which he’d learned to play. But I couldn’t help feeling that the exhibition’s understatement said something about the low expectations of whoever put it together. I’d crept up on it by accident, much as it had been waiting for me with scant hope of being discovered. Maybe it had yet to be completed.

Then there was the 78rpm recording I came across in a Lake District collectibles shop, cosying up to stack of LPs, including Frankie Vaughan: 100 Golden Greats, and Russ Conway’s Time To Celebrate. It was by Barbecue Bob, a name unknown to me but whose renditions of Blind Pig Blues and Hurry And Bring It Back looked jazzy. It wasn’t sensible to buy a record I had no way of playing, but I saw it later on a record auction website, vying for my attention alongside discs by Blue Lu Barker, the Biddleville Quintette and the Cedar Creek Sheikh (Philip McCutcheon). I would never bid for them either unless, like the father of poet Don Paterson, I were offered free needles by a sarcastic hi-fi dealer (Paterson senior, in the 1993 poem of that name, had wanted to buy “an elliptical stylus” for his ancient, beat-up Phillips turntable). Of course, if tempted to bid for My Heartbreakin’ Girl by Billy and Mary Mack I would already have a thimbleful of needles as well as a turntable driven by a fan belt or Heath-Robinson similar. (I’ve already told, in a previous Count Me In, how I found an ODJB 78rpm in a junk shop, even being able to identify its HMV catalogue number.)

Jazz was demonstrably nowhere in the Cotswold town I visited a few years ago. But from about 50 yards while walking the high street, I watched a busker lift a tenor sax from its case and insert the crook. I feared another waste of a wondrous musical instrument as the amplified backing track was switched on and a busking version of The Old Rugged Cross funnelled forth undecorated to convert the heathen of Wiltshire. But, no: this was a version of Lady Be Good that emulated the slippery expressiveness of a Lester Young. The musician was in his 50s, I would have guessed, and possibly one of Traill’s mendicant moderns down on his luck. I sought all my loose change and dropped it into his upturned pork-pie hat – Pres to a T – and gave him a smile.

It was a smile of recognition of the kind Django Bates said he often tried to elicit when standing at a bus-stop or on a tube-station platform. I know the temptation and the feeling that prompts it: that you’d give anything to make eye contact with another jazz-lover – say, by whistling a few bars of Clifford Brown’s Joyspring in the hope that someone close by might twig.

Am I the only person left who whistles? I can’t help it; indoors and outdoors, especially the latter. It’s nearly always a jazz head. No-one responds, even though it must sound intriguing in a land of non-whistlers or those who whistle just nervous nonsense and, when they can get their lips around it, Sweet Caroline.

Which reminds me of my old school pal Dave, who was in charge of organising our end-of-term chaos as teachers abandoned formal lessons on the day before we broke up. Dave whistled snippets as an accompaniment to menial tasks. But it was his dad who opened up a source of serendipity on his death. Unknown to Dave and his two siblings, one of the never opened boxes in their father’s garage contained a rank of jazz EPs in their original paper or cardboard sleeves. They didn’t even know he’d liked jazz. Among the ones I recall were Ruby Braff Swings; Lennie Tristano: Piano Stylist; Big Bill Broonzy: Jazz Original; Charlie Byrd: Stars Fell On Alabama (Riverside); Bob Brookmeyer: The Bulldog Blues; and Gene Krupa: The Rocking Mr Krupa (Clef Records). Dave went on to play drums in a band, his style derived not from Krupa but from an amalgam of Ringo Starr and Peter Kriss (look him up). It didn’t amount to much.

Nothing crept up on me more spectacularly than the mural of jazz musicians on the side of a shop in the Forest of Dean at Ross on Wye. I hadn’t heard of a Ross Jazz Club at the time but I discovered “regular” jazz evenings at the Corn Exchange. Search and ye shall find. But you have to look for it among the poetry, the comedy, the street food (inside presumably), and everything else in that “industrial function space”.

Jazz is always lying in wait, the sub-text over which flows unceasingly the frivolous and the short-lived.