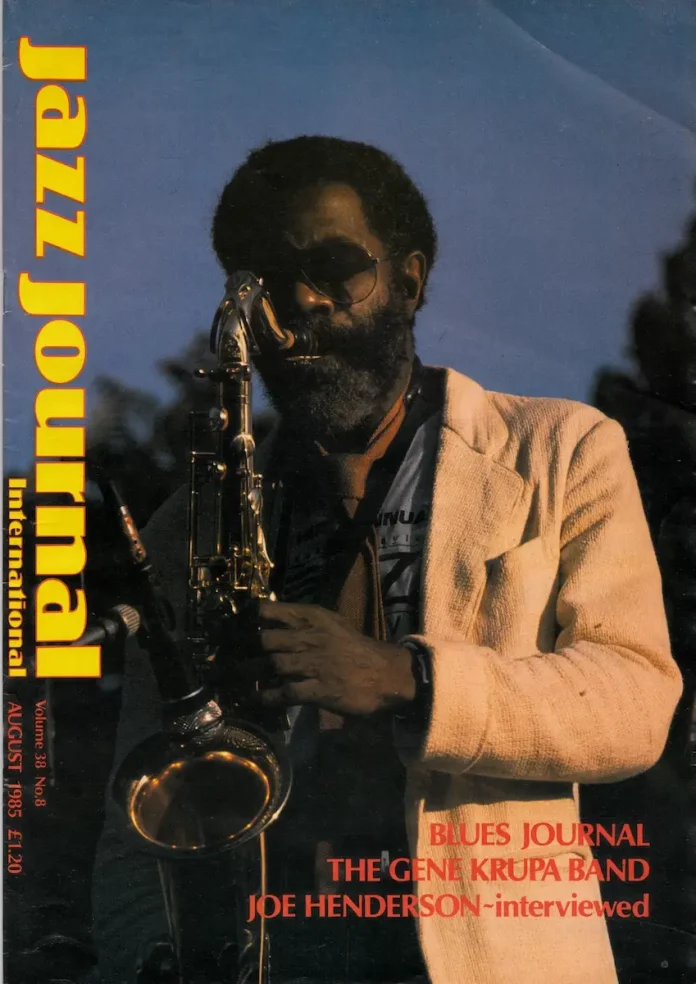

Over the last quarter century, John Coltrane’s influence on saxophone style has been so pervasive that other similar sounding players have often been regarded as Trane disciples rather than distinct individuals. Joe Henderson is one such player, but as he explained, he’d been heading in Trane’s direction for some time before they encountered each other’s music.

For someone whose playing is often abrasive and turbulent, Joe Henderson is surprisingly soft-spoken and courteous. He has an almost professorial bearing (frequent jive-talk notwithstanding), and the musical erudition to match. The cultivated personality begins to fit when you realise that Henderson has, since the late fifties, adopted a studious approach to the business of improvisation, as well as doing a good deal of teaching himself. Which is not to imply that he is a ‘textbook’ jazz man, all theory and no inspiration. As those who have enjoyed his penetrating improvisations will know, he is far removed from dry academe once he’s behind the saxophone. Quite simply, he values the grounding in theory and technique that his education conferred.

‘My intellectual pilgrimage began at Kentucky State College in the mid-fifties. I was there for about a year, then I moved to Detroit and was there for about five years, until 1960. I studied composition, strings, brass, woodwinds, percussion and began to develop an intellectual appreciation of orchestral forms. At that time, jazz wasn’t in the schools – you had to learn it in the clubs – but now it can take place successfully in the classroom situation. I’ve been teaching for a long time, and it doesn’t really matter where the classroom is, indoors or out. You can become equally inspired in the classroom or on stage.’

Presumably though. Joe had heard music before he had read about or analysed it. What early factors set him on his particular musical path?

‘I liked Bartók and Stravinsky and Schoenberg instantly … so when people like Ornette and Eric showed on the scene, they didn’t appear to me to be that unusual or offensive’

‘My early influences probably included everything from sounds I heard in my mother’s womb to when I was six, seven years old, when I had a brother who was an avid fan of Jazz At The Philharmonic. He’d play these Lester Young and Ben Webster records – I heard all the people associated with the JATP prior to learning to play the saxophone. When I picked up the saxophone I had an idea of how it could be played as far as bebop style was concerned. After that, I started playing in high school bands, which didn’t play bebop, and thus got a full appreciation of other kinds of music – classical and marches. I liked Bartók and Stravinsky and Schoenberg instantly; nobody had to prepare me for that. I just liked that stuff; it tended to be a little further out, a little less conventional. And this predates my having heard Ornette Coleman by at least 10 years. I was into an unconventional approach to sound, and so when people like Ornette and Eric showed on the scene, they didn’t appear to me to be that unusual or offensive. I was ready for something out of the ordinary. I used to hang out with classical pianists in my hometown (Lima, Ohio) and so I got a chance to get a full understanding of the piano repertoire. They also played bebop, so that afforded me the opportunity to absorb these things at an early age. I wasn’t even thinking about it, I was just within earshot of it. So when things got a bit technical in the schools, I knew about it already. I had grown up with that.’

While Henderson was in Detroit in the late fifties, he was able to develop a firm understanding of the improvisational process. Numerous talented jazz players came through Motown, including Paul Chambers. Louis Hayes, Yusef Lateef, Billy Mitchell and Thad and Elvin Jones, and Henderson would session privately with them. Consequently, when he moved to New York in 1962, after two years military service, he knew a lot of people whom he had first met and often tape-recorded with in Detroit. Among them was John Coltrane.

‘This pianist friend came up to me and said ”Joe, I heard you on the radio!” … As it turned out, my friend had been listening to Trane. And I didn’t know who John was at this time’

‘I was working with a band in Detroit in 1956 and the bandleader wanted to make some records to get airplay. So we did that. Then, a little while later, this pianist friend came up to me and said ”Joe, I heard you on the radio!” I thought well, that bandleader got some airplay. A few weeks later, this friend said he’d heard me again, and I thought “Hey, this bandleader’s doing a lot of promotion with these records!” As it turned out, my friend had been listening to Trane. And I didn’t know who John was at this time, so there was some way I had gone that was similar to the way John had gone. Some of the same people had influenced both of us. John was older than me, and his success came before mine, so you can see how it might appear that I had been influenced by him. Let me establish that this man left a hell of a legacy for us and I’m really happy to have been associated with him and to have known him. I can’t express how much he raised the level of things in improvisational music, but his influence on me didn’t come so much as one saxophone player to another.

‘I first met Coltrane at a private recording session in Detroit in 1957 and he sat right next to me as we played, and I thought “Wow, this guy sounds like he’s got his scales together.” As a result of his hearing me there, maybe a year later he used to talk about me and he appreciated whatever it was that I had at that time.

‘When I came to New York, writers tried to pigeonhole me, but one time I was standing at the front of Birdland and this cat did me a favour I’ll never forget. There were some good ears standing around too. This guy had known me when I was about 14 in my hometown, prior to my going to Detroit and he said: “Man, Joe Henderson has been playing that way since I’ve known him.” He was saying hands down and make no mistake about it “This little young dude over here had this shit worked out a long time ago.” Whatever it was that I had assimilated in terms of the improvisational thing, how to deal with chord changes and playing the blues, was what I had heard when I was nine and ten from these piano players around my hometown, who were into what everybody later associated with Bill Evans.’

One particular facet of Henderson’s playing that might cause people to connect him with Coltrane is his sound and tone. Had he ever worked on this to any significant extent?

‘At one point I did, and you know I get a lot of compliments for my sound, and from other saxophonists too. But this is something I hear in my own soul. It’s no longer something I consciously work for.’

Anything to do with mouthpiece or reeds?

‘I don’t think so at all. I think that what a person feels will come out of any kind of mouthpiece. I read this about Charlie Parker, that he could play any kind of mouthpiece, horn, setup or reed and get the same sound. It’s within. At the moment I’m using a D Soloist Selmer mouthpiece and La Voz reeds, medium soft. My saxophone was bought in Nice for the 1984 festival and it’s the Selmer Super Action 80. The saxophone I’d been playing on for 26 years was destroyed in an auto accident, where the car caught fire. That was a Mark 6, which I bought around 1955. There’s an incredible story surrounding that horn, which will make you believe in something. It was stolen once from a hotel in which I was teaching. Four years later, a young man came to me for a lesson and kept saying “Joe, would you please try my horn for me? Something’s wrong with this low B.” I kept putting him off, but eventually I did, and I almost fell over. This horn had been in my hands so long that the pearl had worn to fit the curvature of my fingers. This horn had gone all the way to NYC, and a girl had bought it out of a music store. She brought it back to Berkeley; she had it for two and a half years. Then this young man who came by my house had it for a year, having bought it from her. Then he brought my horn back to my house!’

Joe has been living in San Francisco for 11 years now and has been working mainly freelance for about four years since he left the Milestone label. ‘I’ve recorded since then for Contemporary, Enja, Elektra Musician and I’ve got a project that will involve me doing some string writing and using voices. And I’ve got some big band charts that I wrote out a long time ago that still sound quite nice to me. I’d like to go into the studio with some of the cats that played this music, like Pepper Adams, Chick Corea, Ron Carter, Mike and Randy Brecker, Curtis Fuller, Johnny Cole and Lew Soloff. A band full of stars.

‘I’d also like to play different people’s music. One thing that I’ve wanted as long as I’ve been a musician is to become a professor emeritus at interpretation. Becoming known as a great soloist is for whoever needs that sort of ego stroking. Just let me interpret something like it should be and do the greatest job that anyone could – like a craftsman.’