Stan Getz, Miles Davis, Red Rodney, Corky Corcoran, to pick a few names at random, all began playing professionally in their teens. I remember seeing Betty Carter live back in the 80s when she had a young Benny Green on piano. After Green played a particularly adroit solo, Carter turned to the audience and crooned into the microphone “Eighteen!” Early starts are a common theme in jazz.*

Then there is Satoko Fujii. Hailed by critics worldwide as a kind of Duke Ellington of free jazz, the virtuoso pianist, composer and bandleader from Tokyo was pushing 40 when she finally felt fully equipped to began playing her style, a sonic brew that often challenges the notion of what we regard as music. Such sounds are in keeping with her oft-repeated goal of creating something never heard before.

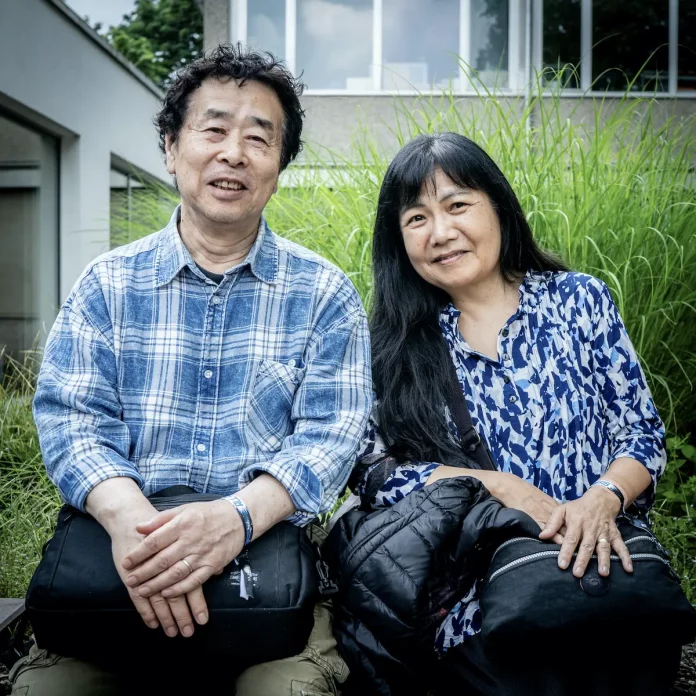

In pursuit of this goal, she has more than made up for lost time. Alone or in partnership with her soulmate and husband, trumpet virtuoso Natsuki Tamura, she has toured extensively in Europe, Australia and North America, playing festivals and club dates and the like. She performs solo, and in duos, trios, quartets and full-blown big bands. Of the latter, she has established and led large ensembles in five cities: Tokyo, Kobe, Nagoya, Berlin and New York City. She and Natsuki – also a composer – have written reams of music for these ensembles, Satoko supplying individual charts for each of her large orchestras. She has released a staggering 100 plus CDs since her debut recording, Something About Water, a two-piano affair with legendary pianist Paul Bley recorded in 1994 and ’95 (released in 1996). To mark her 60th birthday in 2018, she released no fewer than 12 CDs, literally one for each month. Many of these CDs have appeared on her own label, Libra, affording her maximum artistic freedom to record whatever she likes. Natsuki likewise has a number of releases on Libra which include solo trumpet outings, duos with Satoko and his Gato Libre and other ensembles.

Though she’s largely unheralded by the jazz establishment, open-minded critics who have been paying attention are effusive in their praise. Jazz Journal has positively reviewed many of her releases. Other examples of critical reaction are posted on her website and offer insight into Satoko’s appeal. Writing in The New York Times, Giovanni Russonello said “Fujii’s music troubles the divide between abstraction and realism. Plucking or scraping the strings of the piano; covering them up as she strikes the keys; letting the low, rusting textures of a horn section coalesce into harmony: All of this amounts to abstract expressionism, in musical form. But it’s equalled by her rich sense of simplicity, sprung from the feeling that she is simply converting the riches of the world around her into music.” Commenting on Fujii’s piano style in Jazziz, William Stephenson wrote that she plays “in the joyfully aggressive mode of Cecil Taylor”. He adds “She can tear into the most densely packaged melody the way a child tears into a brightly wrapped birthday present: headlong, hungry, unstoppable.” Picking up on the rare partnership between Satoko and Natsuki, Peter Marsh had this to say in BBC Music Magazine: “Fujii and Tamura offer unsentimental beauty, space, silence and humour . . . Proof that music can be emotionally engaging as well as ear tickling.”

Satoko has forged a sometimes crooked path in scaling such critical heights as these. Born in Tokyo in 1958, she began classical piano lessons at age four. Though legitimate study continued through her high school years, she grew increasingly frustrated. As she told me in a 2008 interview, “I did not like the constitution of that [classical] world.” One bright spot during these years was the example provided by Koji Taku, one of her piano teachers. A well-placed academic who had played the piano for the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, Taku gave up this comfortable life in order to play jazz in nightclubs. This move was not lost on Fujii, who decided she ought to give jazz a try.

For a couple of years, she played shows in cabarets that allowed some improvisation, but she grew discontented with her lack of progress in mastering that music and contemplated quitting piano altogether. Instead of quitting, she moved to Boston in 1984 to enrol at Berklee as so many Japanese musicians had done before her. (Natsuki joined her at Berklee in early 1986.) Upon her return to Japan, she worked a variety of jobs, both in and out of music. Again, she found herself becoming dissatisfied with her perceived lack of direction. Finally, at the age of 35 in 1993, she took the bold step of returning to the US, she and Natsuki enrolling in the prestigious New England Conservatory of Music in Boston.

This opened many doors for the couple. At the conservatory, she studied with Paul Bley, who would become an important influence. She also studied composition with George Russell, a mostly rewarding experience. Bley encouraged her to record herself frequently as a way of charting her progress, an important bit of advice she has taken to heart. “You should record 10 CDs as soon as possible,” Bley told her.

As mentioned, Satoko made her debut recording with Bley, a piano duo album. She recalled the sessions in our 2008 chat: “A week before we had the recording session, he said ‘Maybe we can play some standard piece, so just let me know.’ Well, I faxed him some repertory that I wanted to play, and on the day we had the recording session, in the morning, he said ‘Maybe we can just improvise.’ So you know, he’s always like that.”

As for Russell, Satoko found his lessons useful, even though his prickly personality could be challenging at times

As for Russell, Satoko found his lessons useful, even though his prickly personality could be challenging at times. Russell’s course consisted of four sets of classes in succession, and Satoko took all four, one of only two students to complete the entire course. Satoko says “His concept is unique and makes sense.” Explaining that while other theory classes she had taken focused on the rules and limitations of composing, his attitude was that the possibilities for musical composition are limitless. “When it comes to composing,” adds Satoko, “he’s the best one for teaching composing.”

The proximity of Boston to New York City allowed Satoko and Natsuki to forge musical partnerships that would figure in their careers later on. After leaving New England, the couple moved to NYC while they were still on student visas, staying there for 18 months before returning to Japan. In the Apple, they kept their ears open, listening to live music, bonding with other players and performing when they could. This was a rich and rewarding period for them.

They returned to Japan in 1997, Satoko now having the tools necessary to make use of the many sounds – musical and otherwise – she had absorbed up to that point. She was a voracious listener: some of the varied artists and genres she had assimilated included Bill Evans, Coltrane, Ellington, free jazz, ethnic and world music, pop, rock, metal, traditional Japanese music such as min-yoh, and of course, classical. Not a person who responds to visual stimuli, she draws inspiration through her ears. Sound, she tells me, allows her to visualize shapes in her mind that suggest compositions, soundscapes, if you will. Now fully schooled in composing and no longer assailed by self-doubt, Satoko – alone and in conjunction with Natsuki – enjoyed an unprecedented period of activity, writing music, performing, touring and recording frequently.

Then along came the pandemic. While the crisis sidelined the careers of many musicians, Satoko embraced the isolation it occasioned. As she told me in a phone interview in late June 2025 “I loved being isolated and I loved not being on tour, and just concentrate in front of the piano, thinking about music and composing. And I started recording my piano in my soundproof practice room. If we didn’t have [the] pandemic, I couldn’t learn how to put the mic, or how to mix my music.” In addition, Satoko worked remotely with other musicians, continuing to release CDs by sharing music files she combined with her own compositions.

Free jazz? Maybe at times, but the phrase doesn’t tell the whole story

The music born of Satoko’s fortuitous blending of talent, influences, relationships and spirit resists categorisation. Free jazz? Maybe at times, but the phrase doesn’t tell the whole story. In the liners to one of their albums, Natsuki remarks that playing a diatonic scale can earn one “dirty looks” at free-jazz events, a cryptic comment typical of the pixieish trumpeter. To my mind, Natsuki is saying that some of its practitioners think that when free jazz intersects too closely with Western harmony, it becomes invalid. The implication is that Fujii and Tamura’s music is true to George Russell’s notion that there ought to be no limitations to where the music can go.

Accordingly, each of this couple’s ensembles is unique, representing a different facet of their limitless approach to composition and improvisation. Satoko’s music reflects her classical training at times, while at other times it sounds unbridled and free. Tamura’s Gato Libre ensemble limns the spirit of tango or flamenco, both with the compositions and the instrumentation which features Satoko on accordion instead of piano. Likewise, Satoko’s Min-Yoh Ensemble draws inspiration from Japanese folk music without being an obvious recreation. Instead of using traditional Japanese instruments, Satoko tapped the talents of Curtis Hasselbring on trombone and Andrea Parkins, who played accordion with an electronic attachment. As Hasselbring told me when I called to ask about the project, the intent of the group is to reveal the spirit of min-yoh rather than recreate it.

At times the music enters into the realm of noise: raw organic sound in which bar lines disappear and harmony dissolves into organised chaos. Occasionally, Fujii employs human voices in a mix that suggests a primordial soundscape as though touching the spirit of homo sapiens’ earliest attempts at making music.

Frequently in her big-band records, she employs two or more instrumental voices, seemingly engaged in conversation; other times multiple voices make an all out assault on the senses such as in a Mingus composition. Episodes of stark purity resolve into passages of dense, swirling intensity. Sometimes the mood is dark and brooding; other times bright and playful. Particularly notable are occasional duets between Satoko and Natsuki who sound as if they are completing each others’ thoughts as they improvise separate lines which, while not in strict counterpoint, fit together nicely. Other times they play in unison as on the beginning of the album Keshin, which features a long sinuous introduction of the theme that is sheer delight.

At times the music is frantic, other times peaceful and meditative. Throughout her oeuvre, she uses space and dynamics very effectively. Credit her skill as an orchestrator for the ability to make changes in mood sound natural, organic even, as though the direction in which she takes the music were an extension of the composition’s forward momentum.

Artists of rare originality and creativity, Satoko Fujii and Natsuki Tamura show no signs of running out of ideas or losing their inspiration. Indeed, one wonders how many other musicians viewed the disruption caused by the pandemic as more opportunity than hindrance. As long as this extraordinary pair draw breath and remain able to write and play, it’s a bet they’ll be converting the riches of the world around them into musical expression, into sounds never before heard. There may even be a diatonic scale now and then.

Note: Another of Satoko’s pandemic projects was to upload samples from many of her CDs to Bandcamp. Listeners are invited to sample these free of charge at satokofujii.bandcamp.com.

*Though I clearly remember Ms. Carter saying this, I cannot account for a disparity in dates. Mr. Green, it is reported, was born in 1963, joining Betty in 1983, which would appear to make him 20, or 19 at the very least. One of life’s mysteries, I guess.