“Charles Mingus, a musical mystic, died in Mexico, January 5, 1979 at the age of 56. He was cremated the next day. That same day 56 sperm whales beached themselves on the Mexican coastline and were removed by fire. These are the coincidences that thrill my imagination”

So read Joni Mitchell’s liner notes on the 1979 LP that bears Mingus’s name, in a marker of the kind of eccentric coincidences and twists of fate that characterised this unusual project. Mingus, a strange, fresh kind of collaboration which was 40 years old last month, is an outlier in both the Mingus and Mitchell catalogues; an unorthodox audio patchwork quilt of acoustic-electric fusion, skeletal demos, and snatches of dialogue that is somehow out of step with Mingus’s titanic achievements in jazz and also a curio in the Mitchell canon, despite coming at the end of a line of increasingly esoteric jazz-inspired recordings.

‘I always think poetry is kind of like cracking sunflowers with your nails to get the meat out. It’s a lot of work for very little reward, in most cases’

While Mitchell’s associations with jazz had been criticised in the mainstream rock press by writers who found her experimental, category-defying streak somewhat conceited, it was Mingus himself who instigated the project. Dying from ALS, Mingus was fixed on the idea of a final project, an epitaph of sorts, but he knew he needed a guiding light to see it through to fruition.

Having been introduced to Mitchell’s work by producer Daniele Senatore, Mingus and his wife Sue settled on the idea of Mitchell, then 34 and exhibiting an unprecedented artistic bloom not always met with kind reviews, as the person to bring his loose ideas to life. A smoke-screened love of Mitchell’s recent Paprika Plains, a 16-minute free-form epic, was used by Mingus to attract her interest, but it was probably her audacious drag as black pimp Art Nouveau on the cover of 1977’s adventurous LP Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter that piqued his curiosity the most.

On the advice of Sue, Mingus contacted Mitchell himself and presented the idea to the Canadian-born, LA-based songwriter, so adept at unique turns of phrase, of setting T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land to modern parlance.

It’s probably no surprise that the album that became Mingus sounds so strange and offbeat when one considers that neither Mingus nor Mitchell were particularly familiar with the other’s work. Often, bizarre circumstances such as these, where two giants in their respective fields are barely cognisant of the other’s achievements, create the most open flow of creativity. Mingus may have known little of Mitchell beyond her erroneous image as an “acoustic folkie” impudent enough to experiment with jazz structures and chords, and Mitchell, while “honoured” to be summoned, was not intimidated by Mingus’s reputation, knowing as little as she did of his music. The testimony of her drummer John Guerin was enough to convince her to take on the project.

But Mingus’s initial idea of distilling Four Quartets, a deeply spiritual yet pastoral work of rebirth, redemption, and religious eulogy, into musical form did not exactly enthral Mitchell. “There was a lot of pseudo-depth, a lot of tricky wordplay in it, but not a lot of meat”, she said, as quoted in David Yaffe’s Reckless Daughter. “I always think poetry is kind of like cracking sunflowers with your nails to get the meat out. It’s a lot of work for very little reward, in most cases. Even the hallowed ones among them. I didn’t see that it had any kind of great pertinence to Charles’ situation”.

Mingus’s idea was for an English actor to recite passages from Four Quartets, while Mitchell, brandishing the acoustic guitar she had been slowly submerging in her own work, would translate it into “the vernacular”. As she attested, “Apparently, in some churches, you have a guy reading the ‘thee, thou’ text and another one putting it into street or bebop language. And he wanted me to play acoustic guitar. He was an acoustic man. He was a folkie in jazz. He didn’t like electric jazz at all”.

Curiously for a songwriter so admired and renowned for her poetic, abstract lyrics, Mitchell disliked poetry whereas Mingus revelled in it. He had, after all, enlisted Allen Ginsberg to perform at his wedding ceremony with Sue, had performed with the Beat poet Kenneth Patchen, and had written pieces of music to accompany the texts of Frank O’Hara and D.H. Lawrence. In short, Mingus was a words man; his selection of Mitchell to write this epitaph took on a deeper resonance.

Mitchell, quite in contrast to her early reputation as an earnest folkie, was a jazz fanatic

For her part, Mitchell, quite in contrast to her early reputation as an earnest folkie, was a jazz fanatic – she rhapsodised in interviews about Miles Davis (and had the acumen to back it up) and learned to sing from the records of Duke Ellington and Billie Holiday in addition to the vocalese of Lambert, Hendricks & Ross. While Mitchell’s own early records had borne the hallmarks of her roots in the folk-club scenes of Toronto and New York City, albeit with markedly more sophisticated tunings and chord progressions, there was always a leaning towards jazz; on nascent recordings like The Arrangement from 1970’s Ladies Of The Canyon, she flirts with unorthodox jazz-piano chords, and on Conversation, For Free, and Cold Blue Steel and Sweet Fire, from 1972’s For The Roses, adds woodwind and sax colours to her quasi-folk palette.

On 1974’s Court And Spark and especially 1975’s The Hissing Of Summer Lawns the jazz colours became integral as opposed to accentual – Mitchell included her own versions of Lambert, Hendricks & Ross’ Twisted on the former and Centerpiece on the latter, as if to drive the point home. But it was far more than Joni Does Jazz. The singing on songs like Edith and the Kingpin exhibit a real flair for texture and tone, and a lyrical sensibility in keeping with the cream of jazz vocalists.

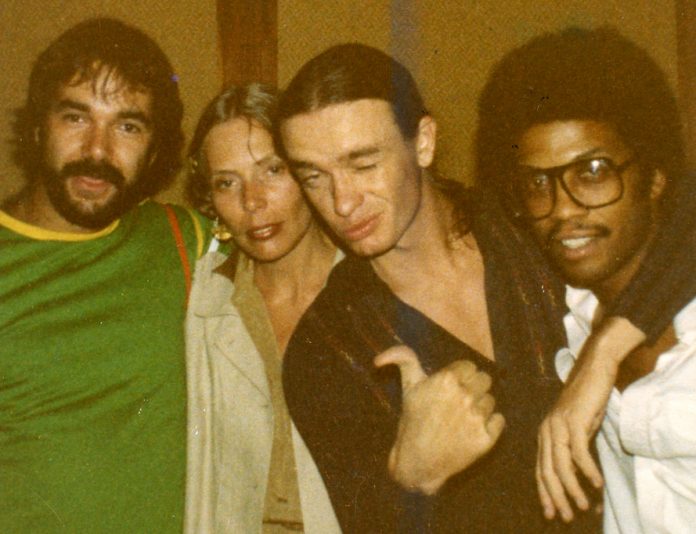

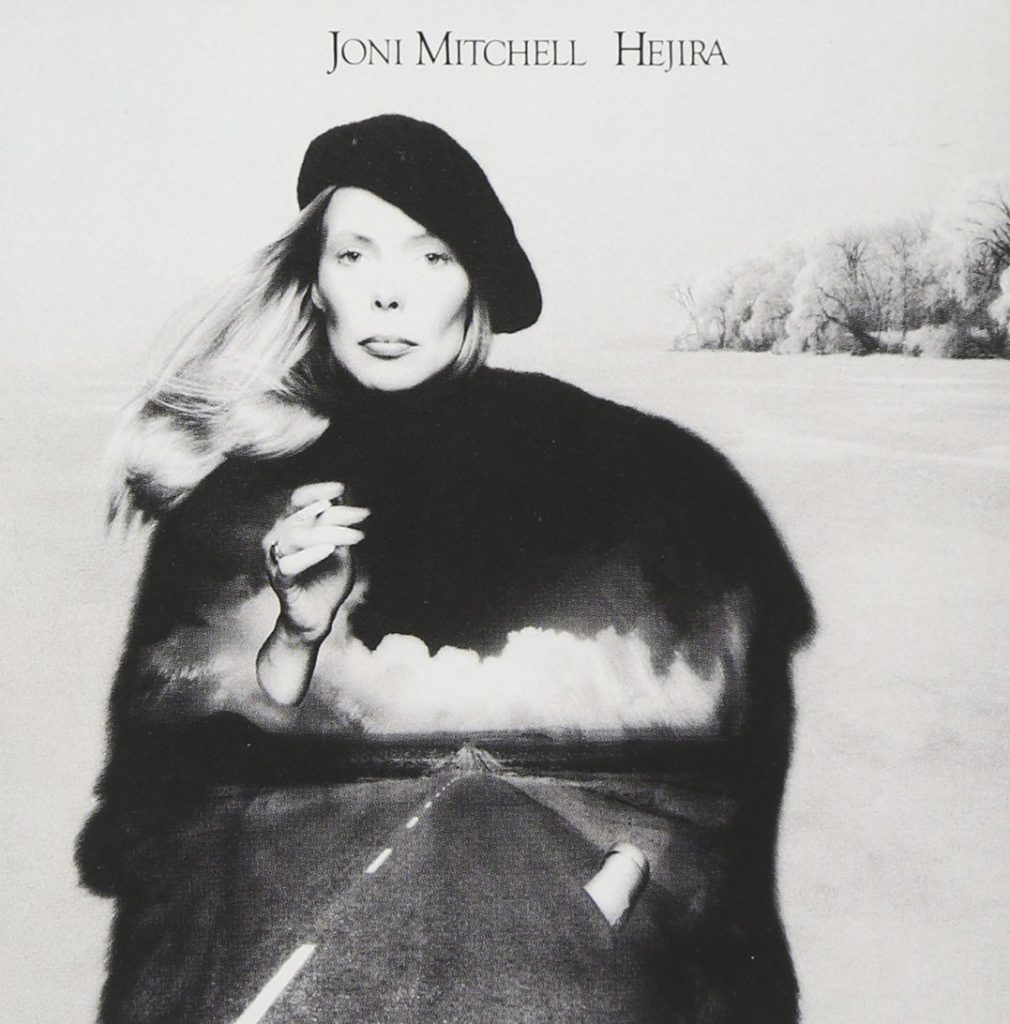

But it’s on 1976’s Hejira that the jazz clothing really started to fit to the shape of her songs. Hejira is one long mood poem, a spectral haze that connects jazz fusion to folk in a completely unique and innovative way – foremost, of course, it’s Mitchell’s songs that do it. But with this album, Mitchell was spoiled with the finest of virtuoso jazz musicians who could take flight on her songs of travel and isolation. Top of the list was Miami’s Jaco Pastorius (pictured with Mitchell), the fretless bass master, and arguably the key to the sound of Hejira and its follow-up, 1977’s vivid, voluptuous double LP Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter. “Jaco was doing everything I was craving – and then some,” she recalled in 2014.

Charles Mingus was listening.

They met for the first time in New York. Mingus, facing the Hudson River in a wheelchair, turned and Mitchell recalled a face that “shone up at [her] with a joyous mischief. I liked him immediately”. Mingus was playful, good-humouredly admonishing Mitchell for an out-of-tune string section in Paprika Plains. The strings had been recorded in two separate sessions, months apart, and spliced together, and Mitchell appreciated his keen ear in noticing their disparity.

Mingus accepted, with grace, Mitchell’s rejection of his Eliot concept and, instead, on this New York summit, presented her with six compositions bearing her name – Joni I to Joni VI. Mingus had composed by singing the melodies into a tape recorder and having arranger Sy Johnson set them to chords. Mitchell’s task, which was not lost on her even at the time, was in finding not just lyrics for them, but lyrics that would convey Mingus’s final wishes for his last project.

Mitchell asked him the meaning behind the first melody. “Some things I’m gonna miss”, Mingus replied.

The result was the languid and elegant A Chair In The Sky. Lyrically, Mitchell inhabits Mingus’s exposed emotions as he fantasises of being “better than ever” in his next life, but maudlinly proclaiming that, for now, “Manhattan holds me to a chair in the sky / with the birds in my ears / and boats in my eyes / going by”.

At odds with Mingus’s work and Mitchell’s own rhythmic recent material, the song, like much of the album, unfolds slowly and hazily, like clouds drifting by. Drummer Peter Erskine explained that the languid tempos of Mingus’s melodies were challenging, and that elongating them to incorporate virtuosic solos didn’t sit right with the mood of the album. It was all about staying distinctive and true to a mood, to a voice.

But for a record that was initially conceived and driven by Mingus, it became very much a Joni Mitchell album.

Spoiled on her most recent projects with musicians who could follow and match her muse, who could give her music a loose feel at odds with her angular lyrical style, Mitchell found Mingus’s initial choice of personnel limiting. “I cut the songs that Charles wrote on the Mingus album with a lot of different bands – bands of his choosing”, she recalled in the liner notes for her 2014 box set Love Has Many Faces. These early sessions included Tony Williams on drums, Stanley Clarke on bass, John McLaughlin on guitar, Jan Hammer on keyboards, and Gerry Mulligan on baritone sax. Mitchell cut the songs four, in some cases five times, searching for a divine truth in keeping with the spirit of Mingus’s music and his hopes for the project. “Although the level of virtuosity was high, the level of invention was low”, she recalled. “It sounded like Bradley’s (a bass and piano jazz bar in New York.) Again, it was ‘meat and potatoes’ jazz”.

Mitchell exercised her iconoclastic streak and called a session with her own choice of players – Herbie Hancock, Wayne Shorter plus some young blood – Peter Erskine and of course, Jaco

Ultimately, Mitchell exercised her iconoclastic streak and called a session with her own choice of players at Los Angeles’ A&M Studios – “my favourites from Miles’ bands – Herbie Hancock, Wayne Shorter plus some young blood – Peter Erskine and of course, Jaco.

“I told them, ‘Everything I’ve cut sounds like a track with a singer – you could take me off and put someone else on – it wouldn’t disturb a thing. I want us to be all woven together like coloured threads into a tapestry. I don’t want the bass and drums locking up like on a track – except on the bridges – the bridges need to groove. The key to this are the words are the leader. There is space between them for individual commentary – stretch out there – but when the words are in – support them”.

Essentially, the personnel comprised the jazz-fusion group Weather Report, sans leader Joe Zawinul. Shorter and Hancock are mixed more subtly, with Mitchell’s vocal and Pastorius’s bass leading proceedings.

Mitchell was keenly aware of the dismissive view held by many of the role of the singer. “You have to understand that in jazz circles at that time, the girl singer was called ‘the chirp’”, she recalled in 2014. “She was decorative, sometimes necessary, but not a real jazzer – not a spontaneous composer … As a result of this prejudice against singers, most players never listened to the words…”

This was, of course, perhaps why Mingus had personally selected Mitchell for the role.

Mitchell’s vocals on the album reach high and low into her range; the piercing octave swoops on The Dry Cleaner From Des Moines (a masterclass in lightning-speed vocalese) sit alongside the elongated phrasing and glissandos of Sweet Sucker Dance and A Chair In The Sky and the tonal variety of the sparse The Wolf That Lives In Lindsey. Her style is conversational and musical; she isn’t showy – the vocals are in service to the material, not the other way round.

The project was a mental challenge as much as an emotional and musical one. “It was as if I had been standing by a river”, Mitchell recalled in the original liner notes, “one toe in the water – feeling it out – and Charlie came by and pushed me in – ‘sink or swim’ – him laughing at me dog paddling around in the currents of black classical music”.

There was, understandably, a leave-taking atmosphere surrounding Mingus at the time; the audio snatches peppered throughout the finished LP (such as the discussion about funeral arrangements on Funeral (Rap)) reveal as much, as did the visits from musicians like Dexter Gordon, Jack Walrath and Ornette Coleman. These funereal feelings were offset by the stresses and the joys of burgeoning creativity.

The emotional pull of the project weighed heavily on Mitchell (“time never ticked so loudly for me as it did this last year”, she wrote. “I wanted Charlie to witness the project’s completion”.) Foremost, perhaps, were the lyrics she was tasked with finding for Goodbye Pork Pie Hat, a requiem for Lester Young first included on 1959’s Mingus Ah Um. Lyrics had already been written, by Rahsaan Roland Kirk in 1976, but Mingus was driving for new revelations. He wanted Mitchell to make vocalese lyrics from John Handy’s sax solo.

Mitchell, walking along the nocturnal streets of Harlem with her percussionist boyfriend Don Alias singing Handy’s solo to herself, later reminisced about a twist of fate: “We came out near a manhole with steam rising all around us, and about two blocks ahead of us was a group of black guys – pimps, by the look of their hats – circled around, kind of leaning over into a circle. It was this little bar with a canopy that went out to the curb. In the centre of them are two boys, maybe nine years old or younger, doing this robot-like dance, a modern dance, and one guy in the ring slaps his knees and says, ‘Ahaaah, that looks like the end of tap dancing, for sure!’ So we look up ahead, and in red script on the next bar down, in bright neon, it says ‘Charlie’s’. All of a sudden I get this vision. I look at that red script, I look at these two kids, and I think, ‘The generations…’ Here’s two more kids coming up in the street – talented, drawing probably one of their first crowds, and it’s … to me, it’s like Charlie and Lester. That’s enough magic for me, but the capper was when we looked up on the marquee that it was all taking place under. In big capital letters, it said ‘PORK PIE HAT BAR’. All I had to do was rhyme it, and you had the last verse”.

Here were Mitchell and Mingus standing in for Charlie and Lester; another duo, another formidable meeting of minds, another bizarre concoction of ideas and styles.

Mingus heard all but one of the songs: the lively God Must Be A Boogie Man took shape two days after his death and was inspired by the opening pages of his autobiography Beneath The Underdog. In it, Mitchell explores Mingus’s multifarious identities (“which would it be – Mingus one or two or three / which one do you think he’d want the world to see”) with an atmospheric arrangement of guitar and bass.

Mingus would no doubt have preferred entirely acoustic arrangements – but you don’t enlist Joni Mitchell without expecting a Joni Mitchell record

The other material is crafted from a palette of Fender Rhodes, fretless bass and tenor sax. Mingus, no matter how wonderfully virtuosic Herbie Hancock or Pastorius may have been, would no doubt have preferred entirely acoustic arrangements – but, as he would have known, you don’t enlist Joni Mitchell without expecting a Joni Mitchell record.

In perhaps a compromise, God Must Be a Boogie Man is built on her silvery acoustic guitar, the flipside being the sheer menace of The Wolf That Lives In Lindsey, an anomalous guitar-and-congas demo, replete with wolf howls, that bites and barks in the middle of the record.

Lyrically, Mitchell, the keenest observer of human foibles and eccentricities, successfully wove Mingus’s life, personality and emotion into the fabric of the music. Vibrant imagery abounds (“like Midas in a polyester suit” from The Dry Cleaner From Des Moines must, surely, be one of the great similes), while songs like A Chair In The Sky bristle with raw emotion and bittersweet optimism.

In Mitchell’s songs, Mingus is both tender and ferocious, loving and tormented.

Sweet Sucker Dance, meanwhile, perhaps best represents the tension between Mingus’s acoustic predilection and Mitchell’s electric explorations. As Mitchell remembered in 2014, “The uncertainty at the beginning [of the song] plays well against the theatre of the first verse which is saying “Tonight it’s a dance of insecurity”. I said to [the musicians] “that’s it”. Their faces said “Really – that’s it?” Years later, one by one, they came to me and said, basically, ‘Do you believe that shit we played?’ It was very innovative”.

‘He said, “OK, motherfucker – you sing your note and my note and you throw in a grace note for God!” I scooped up to it, but neither note was his “hip” note. I left it the way it was’

But Mingus himself, in an episode redolent of the occasionally discordant and protracted album sessions as a whole, “didn’t dig it. He was an acoustic man. Electric bass, electric piano – he was as down on them as Pete Seeger was down on Dylan when he went electric. Charlie had another problem. He said, ‘You’re singing the wrong note!’ I had changed one note in one place – going into the bridge. I said, ‘Well, your note is kind of wistful – a blue note. Mine is optimistic – it helps the words. They both lead – into the bridge’. He said, ‘You’re singing a square note!’ I said, ‘Well, Charles, that note’s been square so long it’s hip again!’ He said, ‘OK, motherfucker – you sing your note and my note and you throw in a grace note for God!’ I scooped up to it, but neither note was his ‘hip’ note. I left it the way it was”.

The record was certainly a challenge. “I was trying to please Charlie and still be true to myself”, Mitchell stated. Mingus’s music, like Mitchell’s, was experimental, reaching, complex. He had been inspired by Charlie Parker and Duke Ellington but he, in turn, absorbed and then subverted these jazz traditions. His expansion of melodic and textural possibilities with scales and bebop harmonies, and his skills as both a composer and bandleader, pushed his musicians to “transcend their abilities,” as outlined by Bob Blumenthal in his original Rolling Stone review.

Joni Mitchell, similarly, was an innovator who pushed her own musicians to transcend their own abilities – it is no coincidence that Charles Mingus wanted to work with her. One of the most sophisticated and accomplished composers in her field, Mitchell’s work with Mingus may not represent the zenith of either artist’s oeuvre, but it does represent a new achievement in collaboration, experimentation and courageous artistic exploration. What could have been a woeful epitaph to one career and the death knell to the commercial shelf-life of another in fact stands as something of a bizarre yet beautiful artistic effort – and almost a triumph. It is a textbook for “crossover” artists to follow, and went some small way in blurring the elitist lines drawn between genres.

Mitchell said that she “was after something personal – something mutual – something indescribable” with this curious project. It’s still not always completely clear whether the Mingus LP always consistently hits its mark, but when it does, it really does. Indescribable – almost; personal – most certainly. “I’m waiting for the keeper to release me / debating this sentence / biding my time / in memories / of old friends of mine…”

A footnote

Wayne Wilentz wrote to say “The tenor sax solo on Goodbye Porkpie Hat is by Booker Ervin, not John Handy. Handy played Alto Sax”, adding “It’s a wonderful article about an album very close to my heart”.

Matthew Barton replies: There’s a bit of confusion on this as both Handy and Ervin play tenor sax on the recording, but my research points to the solo being by Handy; he states so himself in an interview. I can understand where the confusion comes from as the liner notes don’t really specify who it is.